I have to clear my MOVIE DIARY sidebar, so I'm committing it to posterity as an entry into the body of my blog. I review each film in fifteen words or less (which is harder than one might think). This diary doesn't include individual episodes of such TV series as

The Office (US),

Lou Grant, The Bob Newhart Show, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, The Partridge Family, The Honeymooners, 30 Rock, and

Lost in Space. The best movies are marked with 2 stars. Anyway, from January 2009 to early May 2009 (from bottom to top), I watched:

**

My Bodyguard (as always, sweetly friendly film wins affection, thanks to neat cast and Dave Grusin score)

*

House on Haunted Hill (funny, scary slice of late-50s horror with Vincent Price and Carolyn Craig's ear-piercing screams)

**

Abel Raises Cain (affectionate portrait of American master hoaxters Alan & Jeanne Abel, filmed brilliantly by narrator/ daughter Jenny)

**

Carny (strangely lovable, horrifying, scuzzy diary of carny life with extraordinary cast toplining perfect Gary Busey)

*

Agnes of God (excruciatingly boring, save for comparatively radiant Meg Tilly title performance)

**

Contact (better than I remembered--not flawless, but brave, brash, intelligent, and well-crafted by all)

**

Targets (still an astonishing achievement; this time noticed the film's artfully muted color and sound)

*

Atonement (molasses-paced doomed romance could've been told in 15 minutes; an over-rated waste of time)

*

Mary, Queen of Scots (ambitious but frigid period drama with Vanessa Redgrave and Glenda Jackson as battling monarchs)

**

Who'll Stop The Rain (engrossing, exciting, thoughtful Karel Reitz drug-running actioner with superb Nolte, Weld, Moriarty, and Masur)

**

Broadcast News (unbelievably prescient TV news drama from James Brooks, with dynamic Holly Hunter and Albert Brooks)

**

Election (Alexander Payne's funny, insightful high-school-based comedy is powerhouse satire of sexual and political mores)

*

Crazy Love (doc about twisted NYC love affair is sordidly entertaining, but still not particularly outstanding)

**

Prizzi's Honor (exquisite, classy John Huston mob comedy from 1985 holds up sturdily in every way)

*

I'm Not There (Todd Haynes' Dylan biopic is inventive but patience-trying; co-stars a riveting Cate Blanchett)

*

The Delicate Delinquent (one can see why Jerry Lewis turned to directing; he's too good for this material)

**

The Rapture (Michael Tolkin's one-of-a-kind masterpiece; Mimi Rogers' finest moment and a creepy, essential film about faith)

*

The Bourne Ultimatum (we've seen the first two: ho-hum--what's all the fuss about?)

**

42nd Street (zippy, fast-paced 30s-era musical; astonishing cast headed by cute Ruby Keeler; choreography by Busby Burkely)

*

Down to the Bone (dishwater bland indie lucks out with admittedly standout Vera Farminga as drug-addicted mom)

**

Quo Vadis (first and possibly best of 50s-era biblical epics; co-stars the incredible Peter Ustinov as Nero)

*

The Lords of Flatbush (ugly look at 50s leather jacket gang with intriguing pre-fame Stallone and Winkler tossed in garbage)

*

Privilege (the first disappointing effort I've seen from master filmmaker Peter Watkins; a tremendous bore)

*

We Don't Live Here Anymore (shrill and unpleasant domestic disturbance drama ruefully wastes Mark Ruffalo, Naomi Watts, Laura Dern)

*

Each Dawn I Die (engrossing but totally illogical 1939 George Raft/James Cagney prison film)

**

In the Year of the Pig (dryly informative, yet extremely valuable Vietnam overview via radical director Emile De Antonio)

*

Young People (quaint final Shirley Temple musical; unremarkable songs, but Jack Oakie is a powerhouse as vaudvillian dad)

*

The World According to Garp (Hill's disappointing John Irving adaptation sports top-notch supporting work by Glenn Close and John Lithgow)

**

Ryan's Daughter (unabashedly wonderful; exquisite David Lean

Madame Bovary variation with Sarah Miles as surrepticiously naive villain)

*

G-Men (inconsequential 30s-era vehicle with James Cagney as miscast good-guy)

*

Uptown Girls (dunderhead comedy boasts of preternaturally great Dakota Fanning performance and dark lead by Brittany Murphy)

*

The Last Shot (distastefully crude Hollywood-centered comedy with excellent cast slumming big time)

*

Islands in the Stream (slow-as-molasses Hemingway adaptation with glistening Caribbean locale lovingly photographed)

**

The Bellboy (superlative, silent-movie-inspired wackiness from Jerry Lewis, filmed at Miami's Fountainbleu)

*

The War (Ken Burns WWII doc, typically detailed, emotive but a li'l repetitive)

**

Tenacious D (the HBO shorts) (remains stupendously funny even after umpteenth viewing; great earworm songs, too)

**

Playtime (Jacques Tati's picturesque comedy opus is staggeringly inventive, but really should be seen on screen)

**

On Golden Pond (schmaltzy drama with Fonda and Kate Hepburn draws ill-won tears with autumnal photography, music, performances)

**

Wife Versus Secretary (looks like comedy, but it's really a melodrama, starring handsome Gable, Loy & Lombard)

*

Tantrums and Tiaras (complete access can't rescue ultimately empty Elton John home movie filmed by companion David Furnish)

*

2010 (inconsequential

2001 sequel achieves eeriness when HAL and Keir Dullea re-appear in famed set recreations)

*

I Am Legend (utter swill;

this is what we waited years to see?)

**

The Confessions of Robert Crumb (much more playful than Zwigoff's downcast--but superior--1995 movie; Crumb's gamely fun-loving here)

**

Gideon's Trumpet (Emmy-winning TV movie with superlative, penultimate performance from Henry Fonda as history-changing prison inmate)

*

Cinderella Liberty (James Caan and Marsha Mason are effective; screenplay and kid are not)

**

John Adams (ambitious HBO miniseries starts strong, but inevitably ends weakly; excellent leads from Giamatti and Linney)

*

Behind Locked Doors (very slight early Budd Boetticher mental-ward B-movie with Tor Johnson in small role)

*

Skeches of Frank Gehry (Sydney Pollack's final directorial outing is daring if not entirely successful documentary portraying singular architectual genius)

**

Macon County Line (love this 70s drive-in staple, despite awful Max Baer direction; just makes me feel good)

**

L'Enfant (shattering, infuriating, revealing, exhausting; the Dardenne Brothers reach genius with this unparalleled melodrama)

*

Up The Down Staircase (wildly uneven Robert Mulligan urban school soap starring as-always shaky Sandy Dennis)

**

Border Incident (eerily precognative early Anthony Mann immigration drama adorned with crackling black-and-white photography)

*

Shut Up And Sing (diverting but finally threadbare Dixie Chicks documentary teaches us nothing)

*

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter (a major disappointment; dynamic Arkin and Locke imprisoned in so-so-land; based on Carson McCuller's novel)

*

Entourage (season 3) (once-insightful HBO series about present-day Hollywood seems to be running on fumes)

*

Forrest Gump (massive 90s hit is way more morally, politically insulting than I remember; utterly reprehensible)

*

Music and Lyrics (lunkheaded Barrymore/Grant rom-com lacks charm, excepting okay songs by Adam Schlesinger)

**

A Man for All Seasons (fetching, regal Best Picture winner with endlessly fascinating Robert Bolt script and Paul Scofield lead)

**

Papillon (love this Steve McQueen prison drama, regardless of everyone thinking it a snoozefest)

*

The Tarnished Angels (wobbly Douglas Sirk soaper with totally dismissable screenplay based on William Faulkner)

**

Ticket to Heaven (Canada's religious cult drama chills blood despite 80s TV-movie trappings; incredible lead from Nick Mancuso)

**

Bubble (haunting, low-key Soderburgh-directed murder-mystery boasts of insightful all-amateur cast)

*

The Bucket List (Nicholson and Freeman are clearly coasting on already-won charm while stuck with doofus screenplay)

**

Seinfeld (Seasons 1, 2, 3) (we now see it's powered largely by acidic Larry David touch)

**

When Televisions Attack (dizzying pastiche of bad TV from

Vice magazine that'll have you snorting with laffs)

**

Das Boot (Wolfgang Petersen's radically fascinating, perfectly-designed Nazi submarine epic with fantastic art direction, cinematography, and sound)

**

Night of the Juggler (scummy early 80s B-movie with lively cast, colorful early 80s NYC locations, and exciting action)

**

Persepolis (perfection in design and animation; however, surprisingly cold emotionally)

*

Son of Rambow (sort of charming, sort of dull British coming-of-age comedy)

**

The Mist (outlandish, fun, hole-ridden horror from Frank Darabont, though Carpenter's

The Fog is better)

**

Mad Men (season 1) (perfectly-produced, hateful series is so incredible I cannot yet put it into words)

**

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (perfection is had in Brad Pitt/Casey Affleck performances, Dominick's direction/screenplay, Deakins' photography)

**

Be Kind Rewind (unremittingly silly, but heartfelt elegy to the now-dead video store, with inventive "sweded" movie recreations)

**

The Dark Knight (as muddled, dull--and electric via Ledger--as I remembered; recommended only for his performance)

**

The Wrestler (Mickey Rourke, Mickey Rourke, Mickey Rourke!)

**

Doubt (stellar acting from Streep, Hoffman, Davis, and Adams; gorgeous Roger Deakins images; better than expected)

**

Falling Down (Michael Douglas' finest hour; addmittedly overwrought, but well-crafted nonetheless)

**

Soylent Green (70s sci-fi classic more relevant now than ever; don't let clunky sets turn you off)

*

Milk (way overrated; watch

The Times of Harvey Milk instead)

*

Frost/Nixon (pointless Ron Howard movie zinged only by Frank Langella's lead)

**

The Full Monty (still moving British crowdpleaser with a unique ensemble cast and Oscar-winning Anne Dudley score)

*

Comes A Horseman (succulent Gordon Willis cinematography redeems too-thoughtful, slow-paced western; excellent support from Richard Farnsworth)

*

Anchorman (nothing's more embarrassing than bad improv captured on film)

**

Dark City (emotionally cold but visually resplendant 90s sci-fi from writer/director Alex Proyas)

**

True Grit (still wildly enjoyable 1969 western, with eccentric Wayne performance and brilliant Elmer Bernstein score)

**

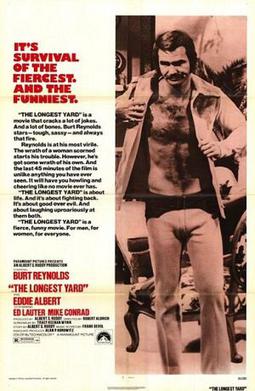

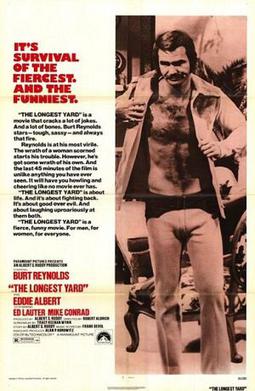

The Longest Yard (1974 version) (best-ever football movie, with incredible editing /split-screen and raucous laughs; one of Burt Reynolds' best)

**

Noises Off (Peter Bogdanovich toys boldly with staginess and earns high marks with yeoman cast)

**

Auntie Mame (snappy Rosiland Russell showcase, colorfully designed and costumed)

*

Hairspray (the musical) (annoying; Michelle Pfeiffer and Christopher Walken are good, though)

**

Paranoid Park (lyrical Van Sant character study of troubled skateboarder with evocative soundtrack and Chris Doyle cinematography)

**

In Bruges (un-freakin'-believeable! Perfect cast excels with perfect screenplay! A real surprise)

**

The Magician (Sneaky, lighthearted and often spooky early Bergman film about wandering performance troupe)

**

Breaking Away (joyous 1979 Oscar-winner is still sharp, exciting, touching, funny and somehow gritty, too)

*

The Fisher King (here, director Gilliam is unwatchably sentimental, but he nevertheless stages stunning moments)

**

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (John Ford's final true masterpiece, with Stewart, Wayne, and Marvin remains heartbreaking and sublime)

**

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (John Huston film about greed never gets old; it's essential viewing)

*

The Fall of the Roman Empire (jaw-dropping sets/costumes, but confused epic tumbles under own weight)

**

Fatso (Anne Bancroft's sole directorial effort is utterly unique, with perceptive, big-hearted lead from Dom Deluise)

*

Brannigan (drab 70s John Wayne actioner set in 70s London; unctious score by Dominic Frontiere)

*

The Horse Soldiers (uneven John Ford Civil War tale is enlivened by pro cast, including John Wayne and William Holden)

*

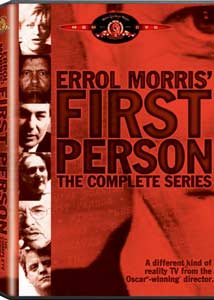

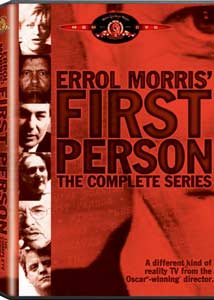

First Person (master documentarian Errol Morris profiles a series of truly unconventional thinkers; weird, and sometimes gross)

**

L.A. Confidential (sorry, but Curtis Hanson's noir-flavored critical darling from 1996 ages rather badly)

*

My Name is Bruce (embarrassingly awful vanity project from Bruce Campbell is not even good for cheap laughs)

**

The Insider (always-worthwhile anti-tobacco screed represents career bests for Michael Mann and Russell Crowe)

**

JCVD (surprise! Van Damme delivers a kick-ass performance!)

**

Gran Torino (Eastwood impresses again with well-modulated, old-fashioned, self-referential entertainment)

**

The Awful Truth (hysterically funny screwball comedy with debonair Cary Grant and ultra-sexy Irene Dunne)

**

Awakenings (Penny Marshall's once too-sentimental medical drama is positively subtle in today's light)

**

The Honeymoon Killers (Leonard Kastle's horrifying, darkly humorous B&W masterpiece about soulless lonelyhearts killers)

*

The Sin of Harold Diddlebock (intermittently funny final Harold Lloyd comedy wears out welcome way too soon)

**

God Told Me To (perfectly bizarre Larry Cohen horror tale with strong spiritual resonance)

**

Hollywood Party (unexpectedly surreal laughs abound in weird Durante/Laurel & Hardy/3 Stooges/Mickey Mouse mishmash)

**

The Tall T (sumptuous, heartfelt Budd Boetticher western starring understated Randolph Scott)

*

The Walker (yet another in a series of recent crushing bores from writer/director Paul Schrader)

*

The Klansmen (a terrible, ugly abomination; Lee Marvin and Richard Burton emerge obliterated)