Lynn and Buddy, my parents, somehow always knew I was going to be a movie nut. That’s the only explanation I have for them taking me to see so many kid-unfriendly movies at the drive-ins back in the '70s (that and the fact they probably couldn’t afford a babysitter, with their civil servant jobs). But they never tried to shield me from very much (though, with sex scenes, they always told me to cover my eyes with the warning term "X-Rated!"). Given that I wasn’t left in tears or bedeviled by nightmares from the movies I saw with them, I guess they sensed everything was copacetic--certainly, child-rearing wasn’t as fraught with as many rules then as it is now.

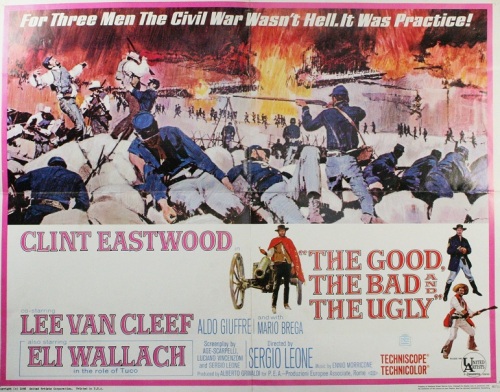

I was surely in their company when they first saw Sergio Leone’s The Good, The Bad and The Ugly upon its US release in the winter of 1968 (this 1966 film was finally released stateside in the last days of 1967). At this time, I was only a year old, so I have no recollections, obviously. What I do know is that it was one of my father’s favorite movies, and even my mom--a lifelong Hopalong Cassidy fan--dug it, too. So we went back to see it, over and over, whenever it popped up on drive-in screens as either a main or second feature (and it was definitely a ubiquitous title at Atlanta drive-ins up until the early 80s). Clearly, my parents cherished this movie, and wanted to catch it whenever they could, and on the big screen, where it still works its most forceful magic.

Though it’s not the first movie I can remember seeing (that placement belongs to a very different western, George Roy Hill’s Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid), Leone’s film is the first picture I can remember being totally enraptured by from beginning to end. It hit me first when I was six years old, in 1972. I can remember my parents and I seeing it together at the Northeast Expressway Drive-In Theater. In my mind's eye, I can now catch the orange-and-pink-tinted sunset as we waited for the sky to get dark enough for the movie to begin. I can remember my dad carrying me up on his shoulders to the concession stand, and I can recall the songs (Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Boxer” and The Moody Blues’ “Nights in White Satin”) that rung out through the hundreds of drive-in pole speakers as we took that short jaunt together.

And, most of all, I can recall feeling completely captivated by the film from its very first frames, when Iginio Lardani’s absolutely enrapturing credits sequence popped up on screen, with Ennio Morricone’s score screaming out into the atmosphere via that sea of speakers. When I see that credits sequence today, I still get an overwhelmingly cozy feeling in my gut. With its cartoonish animation, its oddly-paced editing, with those photos from the film drenched in bold monochromes and overlaid with strangely visceral transitions crafted by sand, smoke, blood, and even frantic paint brushes--just by visuals alone, Lardani’s sequence seems to be crowing from the mountaintops that this is REALLY gonna be something us folks are about to watch! Couple that with the most inspired musical theme ever produced for a film (as a whole, it's the best film soundtrack of all time, in its immense sadness and confidence), with its growling guitar work, blistering trumpets, epically yalping chorales and, of course, that positively insane aeee-aiee-aiiiii yell. (Who're the singers who did THAT? They certainly made their mark on film and music history!) I...well, I...with all this, I can easily understand why any six-year-old in the '70s--especially one such as myself--would immediately be smitten with the film.

Another thing working in its favor, on this front, is that its plot is incredibly straightforward: it’s a search for a stash of gold, plain and simple. And the title itself is also kid-ready: The Good, The Bad and The Ugly. What kid--even a sheltered one--couldn't understand this? The film is even polite enough to let us know who’s who (given that the moral boundaries here are extra-fuzzy), with the introductions of its main characters, each in memorable freeze-frames as exclamations to equally unforgettable sequences, and each emblazoned with those magnificent red cursive letters. Leone’s movie clearly made its mark on me, because I’ve been a lover of both freeze-frames and on-screen graphics ever since.

See, to me, this movie is not great because of its screenplay, which is nevertheless ingeniously constructed and packed with entertaining dialogue; still, it’s not a film with an extreme number of historical profundities, like Leone’s Once Upon a Time in The West, Eastwood’s Unforgiven, Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, or Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch. And, yeah, it’s a movie with three terrific performances at its behest; it’s easy to be carried away by the participation of a heroic, humorous but also alluringly distant Clint Eastwood as Blondie (or The Man with No Name, if you prefer), a terrifying Lee Van Cleef as Angel Eyes (my mom, somehow, had a big crush on the high-cheekboned, blue-eyed Van Cleef), and especially Eli Wallach as the hilariously desperate and grungy Tuco. However, in the end, the star of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly is, front and center, Sergio Leone himself. I don’t find myself agreeing with Quentin Tarantino often about movie history, but I will take into deep account his conviction that Leone’s direction here is the best of all time. I could name a few other directors/titles to throw into the race, but, yeah, this would certainly be amongst ‘em.

From the first shot--which begins as a place-setting long view of the Spanish desert (though set in America, this film is resolutely European) and, with an actor’s simple slide into frame and an expert focus puller‘s abilities, then mutates into a startling close-up of a taciturn shootist out for Tuco’s head--Leone’s direction announces itself as completely unique. His A Fistful of Dollars and For a Few Dollars More were also well-mounted, but here we're in another realm entirely. It feels as if Leone gave his very all to this movie, and yet he still had so much more genius left in him (even with only three movies yet to be credited to him before his death in 1989). But, with The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, he just seems to be having so much fun with the moviemaking process. This sense of joy is completely why we’re left buzzing after watching The Good, The Bad and The Ugly. It’s as if, sometime in 1965 or so, Leone had taken to utmost heart Orson Welles’ assessment of movies as being the greatest train set a boy could have to play with, and then set out to construct the steeliest train set of all time.

You can chalk the casting of those three lead actors (each radically unusual choices for that time), and the rest of the cast, as integral parts to this magnificent plaything. Certainly Leone and producer Antonio Grimaldi knew they had valuable collaborators in composer Morricone, cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli, production and costume designer Carlo Simi, and editors Eugenio Alabiso and Nino Baragli (most of whom with which they'd worked before). Knowing that these artisans were on board, this must have made Leone feel fabulously free to request anything at all from them, with the knowledge his vision would be surely achieved with their work.

The Good, The Bad and The Ugly is utterly overwhelming in its visual detail. The gaudy silver rings on Tuco’s fingers, Blondie's thin brown cigars (which Eastwood despised the taste of), the run-down wooden look of almost every town and wagon and person we see, the use of space and camera angles to inform us exactly where everyone is and what they are doing, the destruction of the war, the sweatiness and dustiness of it all. It’s the trippiest of all westerns. Watching it feels not like we’re being tricked into the seeing the past, but as if we’re actually seeing it, in an artful way we could never hope to imagine. There’s something about that mixture of the European makers, and the American story, that’s just mindblowing. Watching it, you feel like the world has somehow shrunk. It’s America, yes, and right in the thick of the Civil War. But yet we're somewhere else, in some kind of netherworld. It’s that kind of a feeling we can’t put our finger on. It’s the feeling of the TRUE Spaghetti Western (a term that popped up only after this movie arrived, and a term that would change the perception of westerns worldwide forever).

And, by the way, try as they may, none of those other hundreds of Spaghetti Westerns could match this one (though they all provided a new, and perhaps disrespectfully arch, way for viewers to enjoy the genre without having to indulge in the anti-Indian racism that ruined it for many, including Tarantino, who actively despises John Ford, I think, for this reason). When you watch the film, Leone’s masterful angles and cutting floor you, again and again. You get complicated pans and tilts, brilliantly wide long-shots, long tracking shots, inserts intercut with crowd scenes, deep peers into actors eyes (which often fill the screen), clever obfuscations of essential action, haunting silences, blasting noises, and resplendent, repeated reintroductions to Morricone’s superlative score. You just never know what to expect with this movie. It’s a gold mine.

One of the reasons this movie works so well is because it’s not just about good versus evil, like many previous westerns were; there’s that third element there, the one that’s not interested in a moral code, but only in survival. That’s Tuco, and it’s his often jovial, smarmy, revolting presence that elevates the story. It complicates it, and blurs the simpler lines between Blondie and Angel Eyes. At first, we see TUCO as the Bad, and not as the Ugly. But we learn more about him as we go along, and eventually, as we grow to like him, to see him as someone denigrated by the lowliness of poverty, we truly see him as the unfortunate in this story. Of course, one could say the same about Blondie and Angel Eyes, who are also out for survival cash. Maybe that’s the key message of Leone’s film: that we’re all in the same boat, trying to find a way to live, and sometimes we have to rely on one another, regardless of our competing morals, in order to make it all happen. Or maybe this is simply a movie about wise one-upsmanship. Now that I truly consider it, I think the latter is more the case. At any rate, it’s a deceptively complicated movie, and one that rewards repeated viewings (it’s definitely a film that has been viewed many times, by a great many people). Moreover, and most importantly, I would say that it’s also a western that is all things to western lovers: a treasure hunt, a man hunt, a massive battle, a road movie, a showdown, a romp, and an opera.

Moments in the film’s first act that I love: Tuco complaining that he needs water after Blondie first captures him, and then spitting in his face, with Blondie then backhanding him with a terrifically loud whallop (I adore the sound work in the movie; it‘s so over-the-top, it‘s just intoxicating, and the dubbing, while noticeable, is still expertly done; it must be the one dubbed movie that every American viewer can forgive); the hats flying off onlookers as Blondie blasts the chapeaus off their heads; the broken “half-soldier” that provides some of the film’s sparing exposition (including the first mention of “Bill Carson“); Tuco dutifully, and with much expertise, testing out pistols at an ostensibly closed shop, and then stuffing the “closed” sign into the elderly clerk’s mouth--with the clerk’s hysterically tired response (the whole of this beat-laden comedic scene somehow feels like a nod to Jerry Lewis); Leone’s superb matching of Tuco’s gun, aimed at Blondie, against the cannon fire that frees them both; Tuco’s search for Blondie, based on the cigars Blondie leaves behind (Morricone’s score radiantly rings out in this sequence); Blondie, near death, finding out where the gold is hidden, and then Tuco’s hilariously rapid turn-around into becoming his best friend, right before the film’s only fade-to-black.

Leone’s second act begins with Tuco, now in Confederate clothing, speeding up to a monastery, with Blondie as the nearly dried-out corpse holding the key to the plot's mystery. Here, in this section, we’re introduced to much sentiment. We see the toll this Civil War has taken on those that participated in it. Morricone’s music now turns wonderfully mournful, and we really get the sense that Tuco and Blondie are now close to becoming friends (though you’re never really sure with Tuco). Man, how sublime is Eli Wallach in this movie? He’s so funny and tough and weirdly sweet in it. I still think that his participation here alone landed him a rare Honorary Oscar in 2010; with his stubby looks, Wallach had largely been a supporting actor throughout his career, but I truly believe his performance as Tuco ensured him this honor. Similarly, I believe that Morricone’s music here was chief in the minds of those who voted him the Honorary Oscar in 2009, though he had garnered nominations for Days of Heaven, The Mission, The Untouchables, Malena, and Bugsy (amongst literally hundreds of other better scores, though none better than this one or his work on Leone's more ambitious Once Upon a Time in the West).

I

love that Leone and his fellow screenwriters Agenore Incrocci and Furio

Scarpelli (more popularly known as Age and Scarpelli), Luciano

Vincenzoni and blacklisted American actor Mickey Knox chose to highlight

Tuco’s backstory with the appearance of his brother, Pablo (Luigi

Pistilli), a monk at the monastery. This draws us, and Blondie, closer

to Tuco, even after we see Tuco slapping his own face in mock sorrow,

and peeking through his fingers for affirmation, after beholding

Blondie’s desert-scarred, bed-ridden visage (which HE caused). Tuco's

exchange with his brother Pablo, soon after this scene, tells us much:

I

love that Leone and his fellow screenwriters Agenore Incrocci and Furio

Scarpelli (more popularly known as Age and Scarpelli), Luciano

Vincenzoni and blacklisted American actor Mickey Knox chose to highlight

Tuco’s backstory with the appearance of his brother, Pablo (Luigi

Pistilli), a monk at the monastery. This draws us, and Blondie, closer

to Tuco, even after we see Tuco slapping his own face in mock sorrow,

and peeking through his fingers for affirmation, after beholding

Blondie’s desert-scarred, bed-ridden visage (which HE caused). Tuco's

exchange with his brother Pablo, soon after this scene, tells us much:Tuco: What about our parents?

Pablo: Only now do you think of them, after nine years.

Tuco: Nine years? (he smiles big) Mmmm…so it’s nine years? (he shrugs) Nine years!

Pablo: Our mother has been dead a long time now. Our father died only a few days ago. That’s why I was away. He asked for you to be there. But there was only me. (Tuco is clearly devastated by this) And you? Outside of evil, what else have you managed to do? It seems to me you once had a wife someplace.

Tuco: (turning, now snarling) Not one, lots of em. One here, one there, wherever I found ‘em. Go on, preach me a sermon, Pablo.

Pablo: What good would that be? Just keep on the way you’re going. Go away. And the lord have mercy on your soul. (Pablo turns away)

Tuco: Sure, I’ll go, I’ll go--while I’m waiting for the lord to remember me. (stopping Pablo) I, Tuco Ramirez, brother of Brother Ramirez, will tell you something. You think you’re better than I am? Where we came from, if one did not want to die of poverty, one became a priest or a bandit. You chose your way, I chose mine. Mine was harder. You talk about mother and father. You remember when you left to become a priest, I stayed behind? I must have been 10, 12, I don’t remember which, but I stayed. I tried but it was no good. Now I’m gonna tell you something, You became a priest because you were too much of a coward to do what I do. (Pablo slaps Tuco, and then Tuco knocks Pablo down with a more powerful slap, and then we see that Blondie is witnessing this exchange. Tuco helps his brother up, and then turns to leave).

Pablo: Tuco? (but Tuco doesn’t even turn around to look at him). Please forgive me, brother…

Soon after, Tuco joins Blondie on the stagecoach, and they both ride away from the monastery. Here, we get another key exchange:

Tuco: Nice guy, my brother. I didn’t tell you my brother was in charge here? Everything! Like the pope, almost. He’s in charge in Rome. Yeah, yeah, my brother say to me, “Stay, brother, don’t go home. We never see each other. Here, there’s plenty to eat and drink. Bring your friend, too.” (he pats Blondie on the chest) Whenever we see each other, he never let’s me go. It’s always the same story. (Tuco laughs, and Blondie listens) My brother, he’s crazy about me. (long pause) That so, even a tramp like me, no matter what happens, I know there’s a brother somewhere who’ll never refuse me a bowl of soup.

Blondie (smiling): Sure. After a meal, there’s nothing like a good cigar. (Blondie picks the cigar out of his mouth and hands it to Tuco, who receives it, and then takes a deep, restorative breath).

Here, after one of the screenplay's nifitest tricks (with the Union soldiers patting off their greying dirt), we get deep into the Civil War, with Blondie and Tuco captured by Union soldiers and thrust into the battle against the Confederates. This is the section of the movie I like best. It's kind of a side-story (though Angel Eyes is there in the mix, and thus the film's narrative is driven further). But I adore the action of it all, and the fact that it gives both Blondie and Tuco an opportunity to do what's right and just, as a team. I also like that Angel Eyes, as a Union sergeant now, is one who leans towards torturing his army's prisoners, against his hobbled commanding officer's recommendation, thus underlining Angel Eyes' bad moniker. The scene with Angel Eyes and Tuco sharing a slurping meal together demonstrates they are intimates in their worldview, but it also shows that Angel Eyes is ready to use Tuco to get the booty that he truly wants (to the point of almost having Tuco's eyes gouged out). During this torture session, the defeated Confederate soldiers are commanded to sing their wistful song with "more feeling," while Angel Eyes and his henchman try to beat the truth out of Tuco (even though it's Blondie, only, who has the name of the grave at which the gold is buried at). Angel Eyes later calls Blondie in to his quarters, but surprisingly hands him his freedom. Noting Tuco's blood on the dusty floor, Blondie asks: "You're not gonna give me the same treatment?" Angel Eyes, creepily knowing his enemy, smirks and asks "Would you talk?"

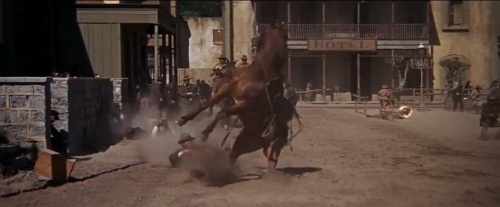

After Tuco and Blondie are separated by Angel Eyes (with Tuco winning freedom from the henchman, and with Blondie joining forces with Angel Eyes), then we view the destruction that the war has caused. This section of this Italian/Spanish movie has more insight into the American Civil War than any other movie had up to this time (it would arguably remain so until the mid-90s, when Ronald Maxwell's Gettysburg, Ken Burns' The Civil War and Edward Zwick's Glory finally broke America's reluctance to look closely, through cinema, at this damaging conflict). This leads to that massive scene, more western- than war-flavored, in which that dude in Leone's first great image shows up again to menace Tuco, who's busy taking a bubble bath. Bullets ring out, and Tuco lets loose with the wisest words imparted in any action film, ever: "When you have to shoot, shoot. Don't talk."

The second act also sets Tuco and Blondie up against Angel Eyes (this is a movie with direction so assured, it blinds you against the holes in its screenplay and the unlikely chanciness of its characters' re-encounters). It leads into western cinema's most mammoth shootouts, set against a battle-torn town (complete with falling cannonballs) and a two-to-five match-up. This is the kind of stuff we watch westerns for. It's ridiculous fun, peering at the always-smiling Eastwood and the shifty, grimy Wallach finally working together, especially supported by Morricone's percussive score and Delli Tolli's sumptuous scope photography. And then it has that wonderfully funny final missive, from Angel Eyes: "See you soon, idiots," and with Blondie handing the note to Tuco and remarking, acerbically, "It's for you."

And then we get to my very favorite sequence in the movie: the bridge, with the Union Captain (Aldo Giuffre) in command, drunk and ready to be done with the fight.

Union Captain (guzzling a bottle of wine): The Rebs have decided that damn bridge is the key to this whole area. Stupid, useless bridge! Flyspeck on Headquarters' maps. Headquarters has declared we must take that ridiculous flyspeck. Even if all of us are killed. Otherwise the key'll get rusty and just be a spot on the wall. And that's not all: both sides want the bridge intact. Intact is how the south wants it, and we want it intact, too. We'll all turn to dust, but one thing's for sure: the bridge will stand unbroken. Is it bad, to speak the way I do to volunteers? I've done a lot worse. I've blown it up in here...BOOM (points to his head). I've destroyed it all. It's a court-martial offense, to imagine, to dream of blowing it up. A serious crime. Even to think of destroying that bridge, it's just (he burps)...

Blondie: Why not really blow it up, Captain?

Tuco: Yeah, Captain, it's nothing. Let's scare the hell out of them!

Union Captain (laughing): I've been dreaming about it. (he stops them, in confidence) I've even worked out a plan. I sure have. If there was a truce, I could save many thousands of men. But what I lack is the guts. (and an explosion rocks them).

Tuco and Blondie's rigging of the bridge is a superb scene. It's engrossing and humongous (and, with thousands of extras, easily sports the film's widest vistas). It is, in short, Leone's perfectly calibrated highpoint. Just when they thought they were free from the war, it impinges on Tuco and Blondie once again, and they are caught up with those same troops they once left behind. This is the path these unlikely friends need to take to the other side, where the cemetery is, and where the gold is buried. One senses that Blondie wants to do it to save the men and please the Captain. Tuco only wants to do it for the gold, but he's willing to go along if it get him what he wants. While rigging the bridge, Tuco tries to suck what he information he can out of Blondie. But Blondie is not ready to give up anything. This back-and-forth dialogue is funny and insightful, and it provides a definite justification for the film's finale. But not before we witness, in one of cinema's greatest montages, a mad volley of cannon fire, with Tuco's ass high in the air, and Blondie's hat pointed downwards, and with the Union Captain grinning, as he dies listening to the bridge's destruction. Still, though, the finale is not so joyous: the scene is filled with dead bodies on both sides. War, really, has no happy endings for anyone.

All of this leads up to the glorious finale, in that odd circular cemetery, where the good, the bad and the ugly share a showdown like none other in cinema history. Time is broken down here into micro-milliseconds, space into half-inches, with bodies backing away from each other, hands drifting slowly towards waiting pistols, eyes shifting back and forth in extreme close-up, and the victor waiting to abscond with the loot. And with one character finally, unforgettably, left lying, screeching out a filthy insult that morphs into Ennio Morricone's aeee-aiee-aiiiii, Leone decamps with Morricone's stunning, aggressive vocals and that meaty guitar. Here, the film withdraws, leaving us incredulous at what we've just seen. Like The Man With No Name, Sergio Leone's The Good, The Bad and The Ugly remains strong in our minds, complete with a sure sense that there could never, ever be anything else like it presented ever again. For me, and for many others, it's the greatest western of all time. Even a six-year-old could see as such.

PLAY THIS NOW!

AND THIS, TOO!

NOTE: This article originally appeared as the #5 entry in Wonders in the Dark's 60-part retrospective on the greatest westerns of all time.

.jpg)