Just to try something a little different, I offer:

100 Things I Love About Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander (in no particular order):

- It was my big-screen introduction to Bergman’s work. I had caught Cries and Whispers, In the Life of Marionettes, Face to Face, and Autumn Sonata on cable during those heyday years of ’78-’82 HBO. Yet I’d never seen his work in a theater, and lemme tell ya, it blew my socks off. At 15, I immediately considered this a formative movie, one that I placed right next to 2001: A Space Odyssey in the pantheon of works that truly let me in on the immense possibilities of cinema. Seeing it as a kid not much older than those in the movie really made an impression on me. It remains my second favorite film of all time. It will probably stay that way.

- The first words we see, printed above the mini-theater set in the film’s first shot: “Not for pleasure only,” referring to the fact that art is NOT just about entertainment.

- The opening scene–the beginning of Christmas Day, 1907–with Bertil Guve as Alexander, lazing away the afternoon, trying to find something to get into. I see this scene as a kind of tour through childhood, playing with toys, then trying to find others to play with, then a reliance on pure imagination, with this nearly pubescent boy settling in on the one thing in his grandmother’s home that sparks it: a nude statue of a female, which becomes bathed in light and begins to move on its own. This is a scene of sexual awakening, I think. Alexander stays underneath a table, frozen in fear for what the future will bring, even though his grandmother bids him to join her.

- The haunting music over that opening scene: Robert Schumann’s Piano Quintet op. 44 II.

- The sets in the film are exquisite, but perhaps none more so than

the red-hued, labyrinthine home of the grandmother. I swear, there’s

something new to look at in this setting every time I see the film.

- That wonderful shot of a carriage passing by vendors of colorful flowers, all set up in the Swedish snow.

- The nativity play, with Fanny and Alexander disguised as angels.

- That scene, once the curtain falls on the Ekdahl family, of pure celebration, with the lights being lowered into frame, the cast embracing each other, the kids chasing each other in little circles, the opulent food being carted in on a long table, and finally the Christmas tree arriving to obscure it all.

- Allan Edwall’s melancholy performance as Oscar Ekdahl, proprietor of the family theater and father to our title characters.

- His character’s final (as it turns out to be) year-end speech to his company, where he casts the theater as “the little world,” trying to make audiences learn about or forget about “the big world” outside. It’s one of the film’s major themes, this comparison, and I find Oscar’s overtly downbeat farewell to it to be quite moving.

- Jarl Kulle’s boisterous Gustav Ekdahl, the restaurant owner, commanding his team not to look down their noses at the actors they’re about to serve, as they’re not as sophisticated as the restaurant’s usual clientele.

- The way Gustav carried the flaming punch bowl, high up, with confidence and skill, careful to see that the fire doesn’t touch his reddened face, as a marching band of musicians play a vivid fanfare behind him.

- Borje Ahlstedt’s idiosyncratic turn as the drunken Carl Ekdahl, first seen singing old standards with his carousing buddies, and then being angrily dragged off to supper by his perpetually worried German wife

- The fact that it’s a movie about ADULT children as well–the three brothers, each in their own ways, have never really grown up. In fact, the only grown-ups in the movie are the women, and this goes for the female children, too: They are inevitably the most even-keeled and responsible people in the movie, underlying Bergman’s view that a mother never really stops being a mother, even before they become a mother.

- Gunn Wahlgren as Helena Ekdahl, perhaps my favorite performance in

the movie. Her matriarchal presence is intense and revealing, as are her

mercurial moods. It’s easy to see the character was once a lauded stage

actress, because she certainly loves the drama.

- Erland Josephson as Isak Jacobi, the grandmother’s Jewish lover and friend. I always found him an overwhelmingly warm and enchanted force in the film.

- Helena and Isak stealing a kiss after he gives her a Christmas gift, and reminiscing about the time her husband caught them fooling around–“It was like a farce by Feydeau.” I also love how she breaks down, sad about old age and the arrival of “the horrible, dirty life.” Isak tries to kiss away her tears, and she quickly comes to her senses.

- Helena: “Are you sad you’ve grown old?” Isak: “I’m certainly not. Everything’s getting worse. Worse people, worse machines, worse wars… and worse weather. I’m glad I’ll soon be dead.” Right on.

- That superb shot of the grandmother, stepping out on the balcony with Isak, donned in her fur coat, saying with all the love in the world: “There is my family,” as she watches them in the midst of a snowball fight. It’s one of the movie’s richest moments of quiet joy.

- Dinner is served, and the kids bring up the rear of the procession to the dinner table. Alexander surreptitiously sticks a mini Swedish flag into the hair of a favorite aunt, to many giggles.

- The energetic line-dance that the family does around the grandmother’s apartment. The song being sung by the family–a Swedish traditional piece–is extremely catchy and you might leave the theater singing it. I always found it amusing, too, that Don Herzfeldt used a version of it in one of his cartoons.

- Gustav breaking out of the dance to canoodle with Maj, a comely maid he has designs on, and then breaking back into the line with a big laugh, right next to his wife Alma (Mona Malm). Another scene of childlike male shenanigans.

- More adult childishness: Uncle Carl treating the kids to a show of scatological “fireworks,” and that big zoom-in to his cigar-smoking face as he lets one rip.

- The alternately bored and enthralled looks on the family’s faces as they listen to Oscar read from the Bible.

- The pillow fight, filled with screams and feathers, and the tinkly sounds of a music box.

- Alma offering Maj (whom she knows is messing around with her husband) a Christmas box, and then slapping her. Maj silently accepts this “box.”

- The mothers kiss their kids goodnight, and Emilie Ekdahl confesses to Alma an impression she has of Alma’s son; “Putte kisses like a real man.” They both find this uproarious.

- As this is an autobiographical memory piece by Bergman, of course we have a scene where (presumed) future filmmaker Alexander treats his sister and cousins to a show of shadows on the wall, as slides in a kerosene lamp tell the prophetic story of a woman being visited by a white ghost. The family will soon have a “white ghost” of their own. The scene ends in spirited screams, and a bemused admonition from Emilie for the kids to hit the sack.

- Maj’s midnight visitation to Alexander, confessing that he can’t sleep in her bed tonight, to which he angrily shuts down. I’d be mad, too: Pernilla August is ravishing as this slightly plump but very sexy maid.

- That goofy sex scene between Gustav and Maj, with the bed collapsing from underneath them.

- Gustav arriving home to chilly stares from his daughter and wife; of course, that doesn’t stop him from trying to get a little more sex in. Another hilarious scene, filled with a rainbow of emotions.

- Carl’s near nervous breakdown at being destitute and beholden to his mother, wondering about the moment where his fortunes turned and his reputation was ruined, culminating in a crippling scene of depression, with Carl clutching his own face in abject despair.

- Bertil Guve’s blacker-than-black eyes and hair, and Pernilla Alwin’s perfectly blonde, blue-eyed Fanny.

- Oscar playing the White Ghost in Hamlet, with his elderly producer (Bergman veteran Gunnar Bjornstrand) looking down at an enraptured Alexander, perhaps spotting the artist the child will eventually become.

- After Oscar collapses, Alexander is again paralyzed with fear for

the future, even after his father’s stricken body has been carted out of

the theater. Only Maj can rouse him to face the inevitable.

- Even at home, Alexander is beset by depression–almost collapsed with grief. Talk of getting a puppy can’t raise his spirits, and neither can molasses sandwiches. Fanny–always steadfast–pokes at him, and he simply says “Leave me alone.” This is his first real experience with death–a subject that would obsess Bergman as a filmmaker for decades to come.

- Oscar’s last words to Emilie, telling her that in death, they will become even closer than they were in life.

- Alexander and Fanny being led to their father’s bedroom, heads bowed down. Alexander gives an almost contemptuous look to the rest of the family as he enters the room; he hates having his emotions on display.

- At the death bed, Fanny dutifully pays tribute to her father, but Alexander tries to hide under the bed. He’s dragged out and, in a horrifying moment, his father clutches his hand, hard, and struggles to speak, his tongue roiling to find the right words before he expires.

- Fanny and Alexander, awoken in the middle of the night to the sounds

of their mother screaming in misery. Bergman and his cinematographer

Sven Nykvist frame this so cleverly, through barely open doors that

reveal only Oscar’s dead body and Emilie walking slowly to and fro,

across the room, screaming and screaming, with the camera cutting back

to the terrified look on the children’s faces.

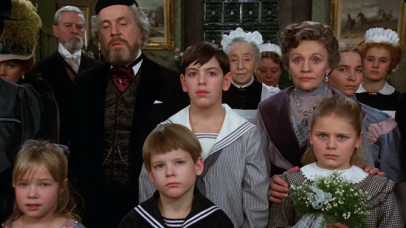

- A stunning funeral procession–the most opulent scene in the movie (filmed without Bergman’s participation, as he was sick at the time–he was beset by hypochondria during the film’s production, a sign that he REALLY cared about it). The scene is spectacularly set to Benjamin Britten’s ominous Funeral March for Queen Victoria.

- And Alexander, walking in the procession, reciting obscenities quietly to himself. Fanny gives him a quick and understanding glance.

- At the post-funeral dinner, Alexander glances at the Bishop offering condolences to his mother. You can see the disgust on his face (Bertil Guve is great at conveying emotions without uttering a sound; for a movie with two children as lead characters, Bergman gives them very few words to say, instead relying mostly on their expressive eyes to tell the story.)

- A great shot concludes this segment: Fanny leads Alexander outside their room, having heard something–three ominous notes being played on a harpsichord. Sitting at the instrument, in a white suit: their now-ghostly father. Edwall’s silent peer into the camera is chilling.

- At the beginning of the second act, a scene where Alexander arrives home to a cold reception, and the other kids are gossiping to each other, presumably about how he’s now in big trouble.

- The introduction of this piece’s villain: Jan Malmsjo as the Bishop Vergerus, who’s been charged with getting the truth out of Alexander. This first battle of wills between the boy and the Bishop is fairly striking–a portent of things to come, and one of my favorite scenes in the film, as it talks about the difference between a lie and the truth. As we come to see, some lies lead TO the truth–that, after all, is the meaning of art. Malmsjo is pretty thrilling in the film–immensely despicable, despite being more famous in Sweden as a song-and-dance man.

- The revelation of the Bishop’s austere home–a stark change from the abundance of the Ekdahl residences, and more superb art direction from set designer Anna Asp.

- And then there’s his ghastly mother and sisters, including one very

obese one, shut away in her room, living life as a freakish pariah.

Bergman’s commentary on such disingenuous religious figures could not be

more clear, or more damning.

- Ewa Froling as Emilie. Her performance really comes into full flower here as she faces more challenges once she makes the fateful decision to marry the Bishop. Utterly powerful is the scene where she argues quietly with him about having to ask the children if they approve of his plan to have them shed their past life completely.

- The wedding scene where, as the vows are being recited, Alexander departs and throws himself dispiritedly upon a full kitchen table, gave me the biggest laugh in the movie. Ridiculously creative!

- Emilie asking her children to include the Bishop in their nightly prayers. Only Fanny complies and the Bishop notices this. He takes this opportunity to needle Alexander some more, finally discovering that he’s also disobeyed the Bishop’s order to leave everything behind. The one thing Alexander brings: his teddy bear. Childhood cannot be denied such small comforts.

- A nearly unrecognizable Harriett Andersson–a long way from Summer With Monika–as the Bishop’s nervous, superstitious maid Justina, with her bandaged hand.

- The scene where Alexander’s imagination takes flight, as he tells

the terrible story of what happened to the Bishop’s former wife and

their two daughters. I remember first seeing this in the theater and you

could feel the audience being silently enraptured by this tale, just as

Fanny and Justina are.

- Another great scene, this time with the Bishop and Alexander squaring off firmly, with the Bishop angry at Alexander’s tale (which we sense might very well be true). Fanny backs her up her brother’s efforts to deny, but eventually, some punishing whacks with a cane are administered.

- That wonderful close-up of the mother’s hand, with a thimble coldly still on a finger, clutching the back of Alexander’s head as he prepares to take his punishment. There’s something so haunting about this shot (it’s the thimble that does it).

- After the punishment and the confession, Alexander gets a few swipes in. “Alexander does not wish the Bishop a good night,” he says. After being forced to kiss the Bishop’s ring, he’s told he’ll be sleeping in the attic until morning. Alexander defiantly screams “YES, YOUR GRACE!”

- Seeking a bit of understanding from Fanny, the Bishop lovingly holds out his hand, and Fanny indignantly turns her head away. This is my favorite moment from Ms. Allwin–a real emotional victory, from a character that seems immanently forgiving.

- The fight for the attic key between Emilie and the Bishop’s bitchy mother is spectacular.

- The Bishop owns a fluffy black cat, so he can’t be ALL bad…

- On a rainy afternoon at a springtime country estate, the grandmother dozes and awakens to a visit from her dead son. He’s apologetic for everything that has happened to the family since his death; meanwhile, she remembers his beauty as a child. Again, a mother is always a mother, even in old age, and even after a child has passed away.

- That great tracking shot as Isak leaves his curiosity shop, dropping a coin into a fiddler’s cup as he heads over to the Bishop’s estate.

- Magic is introduced fully into the film, as Uncle Isak attempts to

buy a chest from the Bishop, but secretly plans to sneak the children

out of the house. Foiled by the Bishop, who slaps the hat of Isak’s head

and screams anti-semitic insults, Isak summons all the power of

illusion and screams to the heavens in order to make this plan work.

This is an extremely memorable moment, and for some viewers new to

Bergman, maybe a head-scratching one.

- I love the scene that has Alexander, under the pretense of looking for a chamber pot, first exploring Isak’s endlessly fascinating house, filled with tons of stuff a kid would love. The smoky photography here is particularly luminous, and I adore that moment where Alexander disappears downstage and then quickly reappears upstage, emphasizing the place’s maze-like features.

- Those superbly creepy shots of Oscar, wandering around in the background, framed by Isak’s collection of chandeliers, as Alexander admonishes him to go back to heaven “because there’s nothing that you can do here.” This is the final time we see the father’s ghost, by the way.

- Alexander, finding the radically unsettling houseboy Aron (Mats Bergman) sleeping with his eyes open.

- A visitation by God, hidden behind a doorway, might be the film’s scariest moment (and this IS a quasi-horror film, in some ways). “Is this the end of me?” The revelation, too, is a hoot.

- Another of the film’s superb scenes has Emilie bidding goodbye to the Bishop, having slipped six sleeping pills into his tea. It’s the one scene where we feel some compassion for the Bishop who, after all, is probably the product of an unloving household. Malmsjo is absolutely brilliant here. “I’m horribly awake,” he says, before crying out in agony to a defiant Emilie.

- The breathing mummy that Aron shows to Alexander. This is Bergman’s personal favorite image in the movie.

- Alexander (to Aron): “If there is a god, then he’s a shit, and I’d like to kick him in the butt.”

- The casting of actress Stina Ekblad as Aron’s locked-away brother Ishmael is particularly inspired, and it really throws your brain into loopty-loops.

- Alexander’s scene with his “guardian angel” is both sublimely comforting and wholly unsettling.

- The sight of the Bishop’s obese sister, writhing in slow-motion flames, is unforgettable.

- …as are the Bishop’s final moments.

- The glorious denouement, where the Eckdahl’s are back together

again. Fanny and Alexander feast on desserts as two new babies–born to

Gustav and Emilie–lie in frilly bassinets. Clearly moved, Gustav happily

regales the guests with a celebration of “the little world, and of

love, kindness, and compassion.

- Meanwhile, the women in family realize that they, now, are in full control of the Eckdahl’s future, with Emilie offering a part in a play by Strindberg to her mother-in-law, who hasn’t been on stage in years, but who seems to be fully considering a possible return, even though she doesn’t like Strindberg (whom she calls “a misogynist”). This is an inside joke, as Gunn Wallgren began her career as one of the premier stage interpreters of Strindberg.

- The extremely eerie re-appearance of our villain, fully underlining Bergman’s film as a kind of horror tale, and a reiteration of the notion that the past is never quite done with us.

- The final moment of the movie brings it around to its beginning: As the grandmother retires to read the Strindberg play, Alexander at last curls up in her lap, once again giving himself over to the power of imagination.

- I love that Lena Olin and Peter Stormare have early roles in Fanny and Alexander. Upon my last viewing, I finally located Stormare (he’s one of the guys that helps Isak with the Bishop’s chest), but I still cannot spot Olin (who is more in evidence in the longer Swedish TV cut).

- The final Bergman touch–those iconic, bright red closing credits, as always, unfolding in silence.

- It was Bergman’s first film made in Sweden after the legendary filmmaker’s four-year tax exile in Germany.

- It’s great that, as one of Bergman’s last film’s, the movie emerged

as a hit, making nearly $7 million at the US box office. (The filmmaker

would go on to make a few TV productions, and a true final theatrical film, 2003’s Saraband with Liv Ullmann and Erland Josephson reprising their Scenes from a Marriage roles).

- In 1983, it hit a record at the Oscars as the non-English language film with the most nominations–six. It ended up winning four: Art Direction, Costume Design, Cinematography, and Foreign Language Film. Sadly, it lost out in Best Director (to James L. Brooks’ Terms of Endearment–a travesty–and Best Original Screenplay (to Horton Foote’s Tender Mercies–less of a travesty).

- It also won the 1983 Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language Film.

- In the 2012 Sight and Sound poll as to the best films of all time, it placed 84th–way too low.

- I adore that, as with many Bergman films, it’s almost completely devoid of music except in key stings and subtle accents.

- It was shot in chronological order–a feat nearly unheard of in modern cinema.

- The larger Criterion Collection version of it (five discs) includes a one-hour “making of” documentary.

- Gorgeous Sven Nykvist photography–absolutely some of his best work.

- The costuming, by Marik Vos Lundh, is resolutely exquisite.

- The makeup and hairstyling are equally lovely.

- Very crisply edited by Sylvia Ingemarsson; despite its length, it speeds by with great haste, and when it’s all over, you feel like you’ve truly been taken on a journey.

- I love its Dickensian quality–it’s a Bergman movie that feels like a

tribute to another great storyteller (which Bergman admitted was so).

- The sound of the Swedish language, particularly as delivered so precisely and with verve by these actors, is absolutely musical. It’s a movie that actually makes me want to learn and speak the language.

- The quick glimpses of the Swedish city streets, or the countrysides, or the flowing rivers and icy thoroughfares–all are completely delicious.

- I even like the film’s elegant movie poster–one of my favorites of all time. I still own and treasure it.

- I can watch it again and again, and never be bored with it.

- I love that it was actually done for Swedish TV, with 2 hours and 12 minutes added to to its theatrical running time. If I ever get tired of the theatrical cut–the one I’ve kind of imprinted on–I can re-experience the piece again anew by watching the TV cut, which is even better, of course. (I apologize to fans in advance for not reviewing that version, but honestly, it's the theatrical version that made me fall in love with it.)

- But, amazingly, the theatrical cut loses none of its power. How was Bergman able to do this? It’s a wonder! (Still, he says, in order to achieve this, he had to “cut into the nerves and lifeblood of the film”). The action clearly troubled him. I can't understand how he was able to do it so perfectly and still keep its power intact.

- Back in ’83, I took one of my first and favorite girlfriends to see the movie, and she loved it; it remains one of my favorite moviegoing experiences (though she now remembers that she absentmindedly talked through part of the film--I think I was so engrossed with it that I've forgotten this). Fanny and Alexander also played at an Atlanta 99-cent second-run house I worked at as a teenager, and I remember the projectionist getting the reels mixed up because it was such an uncommonly long movie; I had to clue him in about his mistake, and it took all night to fix. The film did exceedingly well at the Toco Hills Theater, drawing in big crowds for four weeks--an amazing feat for a three-hour Swedish film in such an locale.

- Finally, I adore that it’s a movie with such wonderful, never

overdone or sentimentalized insights into the filmmaker’s own troubled

yet vibrant childhood as the son of a strict Episcopal pastor. It’s both

a perfect Christmas film and a justifiable entry into the horror

pantheon, and there are not many movies that can boast of that

distinction. And I can deeply feel the care Bergman and his team put

into every frame. I love that it’s a film so many other people adore,

and as such, it will live forever. It's a movie that resolutely explores and enriches my heart. I hope you know now how much I adore it.

NOTE: this review originally appeared in 2015 as part of WONDERS IN THE DARK's genre overview called THE CINEMA OF CHILDHOOD. Check the whole lineup out here: