In responding enthusiastically to MovieMan's wildfire-like

Reading the Movies meme over at The Dancing Image, I've come up with my top forty movie books. Listed roughly in order of importance, they are as such (and I've recently added notations where I gather these books are OUT OF PRINT and thus need special pursuit):

1) The Cult Movies series (1,2, & 3) by Danny Peary (Delta 1981, 1984, 1989)

1) The Cult Movies series (1,2, & 3) by Danny Peary (Delta 1981, 1984, 1989)

2) Guide for the Film Fanatic by Danny Peary (Simon and Schuster, LTD, 1987)

3) Alternate Oscars by Danny Peary (Delta 1993)

For my money, Peary is the finest film writer out there. He transmits passion, knowledge and originality of thinking without ever becoming pretentious or unintelligible. He's funny, engaging, and has seen a whole lotta stuff. He's obviously an authority that deserves to be read again and again--and with his breezy style, it's easy to do so. The

Cult Movies books are the best-looking non-color film books out there, too--each of the series' 200 entries come complete with credits, full synopses, 5 or so pages of analysis, and a few well-chosen photos; the movies he chooses to cover come from all genres and eras (Peary is a truly democratic film writer).

Guide for the Film Fanatic is the book I run to before or after I've seen something notable; I must have burned through four copies of the tome over the years. And

Alternate Oscars does brilliantly what we'd all like to do: mete out justice to the movies and actors that deserved the awards; his choices here are sometimes unfailingly personal, but the author always makes convincing arguments. He's now concentrating on sports writing but as a movie aficionado, Danny Peary is the

best! No contest! (all are out of print)

4) Kiss Kiss Bang Bang by Pauline Kael (Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd, 1970)

5) Taking It All In by Pauline Kael (Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd, 1986))

6) 5001 Nights at the Movies by Pauline Kael (Holt Paperbacks, 1991)

I could list many more works by this legend, but I kept it down to these three--the first two were my teenaged introduction to the former

New Yorker film writer, and the latter is the three-inch-thick guide to movies that also, to this day, is a regular reading stop for me. Kael often disappoints me with what she thinks of my favorite movies (she called

2001 "the biggest amateur movie ever made"), but her writing is so hard-scrabble vivid that I can forgive her 1000 times over for making me feel like a fool (though her opinions have rarely changed my mind). My circa-1989 NYC roommate Gary Sherwood once received a call from her in response to a letter he wrote regarding her favorable review of Tim Burton's

Batman; through him, she asked me what my favorite movie thus far of 1989 was, and I responded

sex, lies and videotape. She was not pleased, but I still love Soderburgh's movie. And, may I say, it's held up better than Burton's bloated epic has.

7) The Stanley Kubrick Archives by Alison Castle (TASCHEN America Llc, 2008)

The mindbending publishing company Taschen released this massive $200 look into Stanley Kubrick's purview in 2008, and it promptly took first place status in the Kubrick book sweepstakes. Its overwhelming first half consists of frame blowups of images from each of Kubrick's works, from

Killer's Kiss to

Eyes Wide Shut (the source being Kubrick's prints of his own movies). And the extremely exacting latter half covers the ins and outs of each film's making, replete with Kubrick script pages, memos, and photographs. The book even covers his short films, his little-seen first feature

Fear and Desire, his early photographic output for high school and

Look magazine, and failed projects

Napoleon, The Aryan Papers, and

A.I. Stunningly designed and colored, this would be my choice for the nicest-looking, most revealing film book available. I note, happily, that my copy is signed by Malcolm McDowell on the full-page repro of his first

Clockwork Orange close-up

8) Hitchcock/Truffaut by Francois Truffaut (Simon and Schuster - Touchstone Books, 1967)

8) Hitchcock/Truffaut by Francois Truffaut (Simon and Schuster - Touchstone Books, 1967)

The ultimate in classic conversation between fine filmmakers. Its revelatory quality is absolutely unmatched.

9) Inside Oscar (10th Anniversary Edition) and Inside Oscar 2 by Damien Bona and Mason Wiley (Ballantine Books 1996; Ballantine Books 2002)

An apologetically reverent look at film history, as seen through each year's politically-driven race for the Academy Awards. You'd think it'd be an easy thing to list all the conglomeration's nominees and winners, as this book does perfectly in its final section, but so many Oscar books screw things up with typos and just-plain-wrong information. Not this one.

Inside Oscar is the definitive Academy Award overview.

(out of print)

10) Joe Bob Goes To The Drive-In by Joe Bob Briggs (Delacorte Press 1986/1987, with intro by Stephen King)

10) Joe Bob Goes To The Drive-In by Joe Bob Briggs (Delacorte Press 1986/1987, with intro by Stephen King)

Joe Bob (aka John Bloom) brings his unbridled joy to the discussion of bad (and good) filmmaking. His chunky, without-boundaries film writing reminds us of why we like movies: it's cuz they're fun. You know...fun? Remember that? It was on the basis of this book that I chimed in with my bosses at TNT in the mid-90s in recommending him as the host of that network's memorable

Monstervision franchise. I'm not bragging--I'm just sayin'...

(out of print)

11) This is Orson Welles by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (Harper Collins 1992)

Reading this, one realizes that Welles' reward as a cinematic genius wasn't necessarily in the making of often (but not always) great movies, but rather in the living of an always rich life. If we could have an earthly existence that held 1/1000th of the excitement that Orson felt, we'd be very lucky indeed.

12) Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of a New Hollywood by Mark Harris (Penguin (Non-Classics), 2009)

The best film book of recent years takes a gander at the five movies nominated for Best Picture at the 1967 Oscars:

Bonnie and Clyde, Doctor Doolittle, The Graduate, Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, and

In The Heat of the Night. Harris follows the gestation of these movies right up to their release and acclaim (or lack thereof). In doing so, he chronicles the late 60s seachange that led to the last golden era of movies, the 1970s. It reads like a masterful suspense novel--that's how engrossing it is.

13) Making Movies by Sidney Lumet (Vintage, 1996)

This is one book that deserves to rank as the future's #1 textbook for budding filmmakers. Lumet's attention to detail even extends to the direction of extras (he rightfully says that NYC extras are better than LA extras, because the NYC participants are real actors rather than fame-seeking hot-doggers). It's an extraordinary late-career contribution to film writing from one of cinema's greatest craftsmen.

14) The Making of Kubrick's 2001 by Jerome Agel (Signet; First Edition 1970)

14) The Making of Kubrick's 2001 by Jerome Agel (Signet; First Edition 1970)

I've had a copy of this book on my person ever since I saw

2001 when I was 11 (in 1977). I've only ever seen it as a pocket paperback, but it was clearly printed a lot, because I've never had any trouble finding a copy after my last one had fallen apart. Agel was a nimble media writer who'd worked closely with Marshall McLuhan on a number of tiny-but-dense paperbacks like

The Medium is the Massage and

Is Tomorrow Today? It's not surprising, but is nonetheless a miracle that he devoted time to compiling this incredible overview of one clearly groundbreaking movie. An Agel book is unmistakable in it layout, typeface, and bouncy form of organization. Here, along with that unique print voice, you will find numerous Kubrick interviews, talks with almost everyone associated with the film, critical reactions (often printed in full), fan (and non-fan) reactions, film quotes, and an amazing 96-page photo compilation that features cut scenes, behind-the-camera views, and frame blowups, all meticulously captioned. The best book ever produced dealing with a single title.

(WAY out of print)

15) The Ingmar Bergman Archives by Paul Duncan and Bengt Wanselius (TASCHEN America Llc; Har/DVD/Fl edition 2008)

Like its Kubrick-centric predecessor, Taschen's richly illustrated analysis of the great Swedish filmmaker's career is essential to our understanding of Bergman's immutable worth.

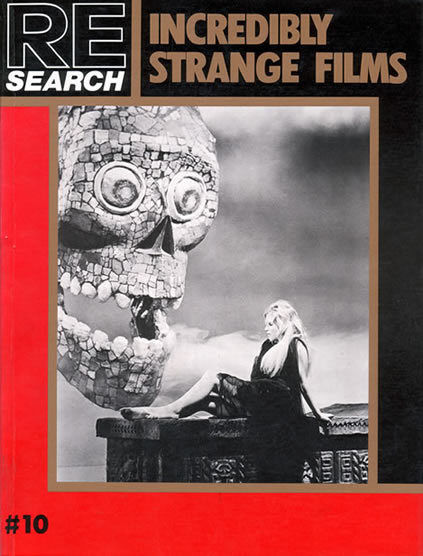

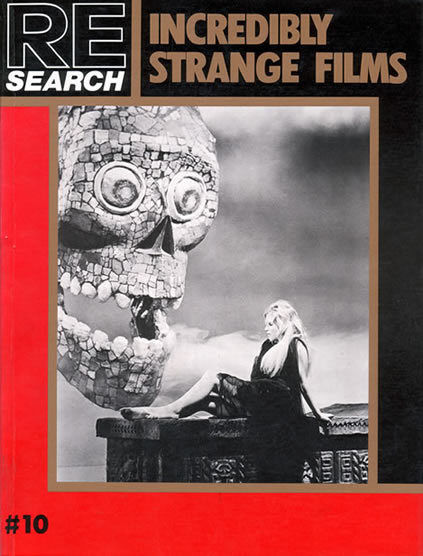

16) RE/Search #10: Incredibly Strange Films by Vivian Vale and Andrea Juno (RE/Search, 1986)

16) RE/Search #10: Incredibly Strange Films by Vivian Vale and Andrea Juno (RE/Search, 1986)

The idiosyncratic San Francisco publishing company RE/Search threw into the film book race with this loving look at outside-the-mainstream filmmakers like Russ Meyer, Ted V. Mikels, Doris Wishman, Larry Cohen, Dave Friedman, Hershell Gordon Lewis, and Ray Dennis Steckler. A compilation of interviews and essays, as well as rare photos and movie ads, it's essential reading for filmfans looking for something different.

(out of print)

17) Hollywood on the Riviera: The Inside Story of the Cannes Film Festival by Cari Beauchamp and Henri Behar (William Morrow & Co; 1992)

There've been scads of books written about the Oscars. But only one has been penned about the equally (if not more so) political machinations surrounding the world's leading film festival. This is that unmatchable book.

(out of print)

18) The Motion Picture Guide by Stanley Ralph Ross and Jay Robert Nash (CineBooks, 1983)

In 1983, L.A. actors/writers Ross and Nash released this photo-less 17-volume set which examines, apparently, every movie ever made. Pre-IMDB, it was the go-to spot in learning the participants in any film you could think of. What was Peter Lorre's character's name in

Beat The Devil? Who photographed

Heaven With A Gun? Who wrote

A Hatful of Rain? And what songs were used in

American Graffiti? You could find the answers here. WARNING: the authors often synopsize the greatest movies in rash detail (their entry for

Gone With the Wind lasts five pages, and that's in incredibly tiny type), so if you are sensitive to spoilers, don't read everything. And, I must say, my opinions of movies don't often jibe with theirs (they give

Taxi Driver a half a star--they clearly like older movies). But, even if these guys sometimes seem as if they don't know what they're talking about,

The Motion Picture Guide is a still a breathtaking achievement. The authors continued with yearly annuals until the 1990s, when they were replaced by Edmond Grant and Ken Fox.

(WAY out of print)

19) Scorsese on Scorsese by David Thomson (Faber and Faber, 1989)

Another completist overview of a great filmmaker's career, told with utter honesty by the man himself. Regularly updated.

20) Reel Facts by Cobbett Steinberg (Penguin Books LTD; Rev Ed edition, 1981)

Reel Facts was a book that I picked up in an early edition when I was 10, in 1976. It clued this kid in to all major film festival and critics groups awards. There have been other books that have done what it does (including the later-cited

The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards by Michael Gebert), but Steinberg's book is the only one that generously includes, in full, 35 years of the Harvard Lampoon's hilarious worst-movie awards (which takes up, thankfully, about 70 of 500-plus pages).

(WAY out of print)

21) The Whole Equation: A History of Hollywood by David Thomson (Little, Brown; 2005)

A dazzling, and essentially personal view of film history that takes into account budgets, box-office, executive predilictions, decade zeitgeists, and filmic quality. It boggles the mind, really, in terms of its pervasive overview, and deserves to be a textbook mainstay.

22) In The Blink of an Eye by Walter Murch (Silman-James Press; 2 Revised edition, 2001)

The essential tome on film editing and sound work, written by a master of the crafts.

23) The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968 by Andrew Sarris (Da Capo Press, 1969)

The immutable 60s classic that first posited the auteur theory.

24) A Short History of the Movies by Bruce Kawin and Gerald Mast (Longman; 9th edition, 2005)

The eternal movie textbook, detailed and loving.

25) 50 Years of the Academy Awards (1977 edition) by Robert Osborne (Abbeville Press, 1977)

I got this 1977 book for Christmas that year, and its no-nonsense style, plus its copious illustrations, spurred me on to examine all major Oscar players. It's been updated repeatedly by the distinguished TCM host--up to the 80th year of the awards--but I have a fondness for this edition, particularly.

(out of print)

26) Horror Movies: Tales of Terror in the Cinema by Alan G. Frank (Book Sales, 1974)

26) Horror Movies: Tales of Terror in the Cinema by Alan G. Frank (Book Sales, 1974)

I received

this book for Christmas in 1975. I was a horror movie fan and a regular reader of Forrest J. Ackerman's

Famous Monsters of Filmland, but I had never seen anything like this British-based horror movie book decorated with scads of fascinating photos. It's out-of-print now, but it should be in the library of any self-respecting horror movie fan (along with the more complete

Nightmare Movies: A Critical Guide to Horror Movies by Kim Newman, which just missed making my top 40).

(out of print)

27) The Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film (Vols. 1 & 2) by Michael Weldon (Ballantine Books, 1983, 1994)

Weldon--the master viewer of B-Movies, and the editor of the absolutely essential

Psychotronic magazine, weighs in on all fronts, with great humor, passion and precision.

28) Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide by Leonard Maltin et. al (2000 edition published by Signet on September 1, 1999; published yearly)

The perennial movie guide is difiicult to determine in origin. I seem to remember it appearing on bookshelves as early as 1976 (along with Steven Schafner's now-forgotten

TV Movies). Staunchly mainstream, it's always does well for a quick look at a movie you're about to watch, but as years progress, older titles are deleted. So, beware...

29) Scenes from the City: Filmmaking in New York by James Sanders (Rizzoli, 2006)

This amazing volume focuses in on movies shot on the greatest soundstage in movie history: New York City. Wholly backed by the New York City Mayor's Office of Film and Television, it features a pleathora of fantastic behind-the-scenes photos of all your favorite NYC-shot movies, complete with exacting locations (the scene from

Annie Hall you like? Filmed at 67th and 2nd). It's an incredible work that's as much a travel guide as film book.

30) Stanley Kubrick Directs by Alexander Walker (Harcourt Brace Co; 1972)

Originally published in the early 70s (and recently updated in the 90s in order to cover the director's entire career), this critical dissection of Kubrick's works comes from a close personal friend of the director. As a kid, I referred to this book--which had incredibly valuable frame blow-ups and Walker's rich insights--many, many times. Its pages are instant nostalgia.

31) Defining Moments in Movies: The Greatest Films, Stars, Scenes and Events that Made Movie Magic, edited by Chris Fujiwara (Cassell Illustrated, 2007)

31) Defining Moments in Movies: The Greatest Films, Stars, Scenes and Events that Made Movie Magic, edited by Chris Fujiwara (Cassell Illustrated, 2007)

The most recent book on my list reads like a printed version of the web's most impassioned blogposts. Through the words of over 100 internationally-reknowned film writers, it recounts the major moments in film history, from 1899 to 2007. Beautifully illustrated and written, it makes me feel like an absolute dumbkopf--which I love, because I'm always looking to learn more.

(out of print?)

32) Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho by Richard Anobile (Macmillan, 1974)

With this book, Anobile pioneered the now-dead fotonovel. He painstakingly looked at each of the key frames of Hitchcock's masterpiece and reproduced them in book form. This, of course, happened before each of us had VCRS and DVD players in our homes. So arriving into classrooms, as I once did with his books, was something of an achievement. He went on to do fotonovels for

Ninotchka, Alien, Casablanca, The Maltese Falcon, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Dr. Jeckyl and Mr. Hyde, and

Frankenstein, but Anobile's look at

Psycho would remain his most valuable contribution to film publishing.

(out of print)

33) Final Cut: Art, Money, and Ego in the Making of Heaven's Gate, the Film That Sank United Artists by Steven Bach (Newmarket Press; Revised edition, 1999)

Bach's unsparing look at Michael Cimino's studio-toppling making of

Heaven's Gate--still, to me, a vastly underrated movie that popped up wrong-place-wrong-time--stands as a cautionary tale for young filmmakers who, tainted with a taste of success, think they can do anything under the sun.

34) Off-Hollywood Movies: A Film Lovers Guide by Richard Skorman (Harmony, 1989)

A guilty pleasure. The writing isn't notably superb, but the films cited are.

(out of print)

35) The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards by Michael Gebert (St. Martins Mass Market Paper, 1996)

Gebart's vastly personal take on the history of movie awards is too vehement to be ignored. A great pocket-sized book to carry with you anywhere, if you're a movie lover. But I wish it were more complete, and twice as thick.

(out of print)

36) Hollywood Rock, edited by Marshall Crenshaw and Ted Mico (Harper Collins; 1994)

The history of rock n' roll and all other related music genres, via movies. Crenshaw does little writing here, but his editing is unparalleled. If you like movies AND music--as I suspect many movie writers do--this is essential perusing.

(out of print)

37) The Film Encyclopedia by Ephraim Katz (Collins; 6 edition, 2008)

The unquestionably ultimate source for biographical film information. Even in this age, it often trumps the IMDB for insanely accurate information about any film worker's career.

38) Film Forum: Thirty-Five Top Filmmakers Discuss Their Craft by Ellen Oumano (St Martins Press, 1985)

Godard, Altman, De Palma, Silver, and many more world filmmaker nitpick every single aspect of filmmaking in this singular hardback. A must.

(out of print)

39) Directors in Action: Selections from Action, The Official Magazine of the Directors Guild of America by Bob Thomas (Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1973)

This very rare tome collects interviews with a bunch of forgotten (read: Paul Williams) and unforgotten (read: Hal Ashby and James Bridges) filmmakers, and really gets into the niggling details. A treasure.

(WAY out of print)

40) Picture Shows: The Life and Films of Peter Bogdanovich by Andrew Yule (New York, NY Limelight Editions, 1992)

Only his close personal friend Orson Welles has come close to the life lived by this incredible moviemaker/film writer, who's made his way from print to Corman to filmmaking greatness to tragedy and

The Sopranos in a remarkably colorful career. Though the book doesn't cover Bogdanovich's complete output, it does point to key decades radically experienced.

(out of print)

I should note that I love the writings of

J. Hoberman and

Roger Ebert, but I've relied on their daily writings rather than their books. And I'm ashamed to say: I've read little by

James Agee. Gotta get on that!

ART DIRECTION: THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN, Fiddler on the

Roof, The Boy Friend, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, Nicholas and Alexandra

ART DIRECTION: THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN, Fiddler on the

Roof, The Boy Friend, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, Nicholas and Alexandra