Saturday, June 20, 2009

MASTER LIST #13: The 101 Best Films of the 1970s

In response to the current poll being held at the magnificent Wonders in the Dark, I decided to commit to posterity my 101 favorite films from the 1970s. I came of age in the 1970s, so I saw about 65% of these titles in first-run theaters (it was an unbelievable time to be a budding film lover--so much so that I haven't enough words to describe it here). So, in order, based on (1) influence, (2) personal affection, and (3) overall quality, here's my list, with short commentary:

1) The Godfather and The Godfather Part II (Francis Ford Coppola, 72/74)

2) Annie Hall (Woody Allen, 77)

3) A Little Romance (George Roy Hill, 79 (France/USA))

4) Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 74)

5) Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 76)

6) All That Jazz (Bob Fosse, 79)

7) Eraserhead (David Lynch, 77)

8) Days of Heaven (Terrence Malick, 78)

9) The Last Picture Show (Peter Bogdanovich, 71)

10) Nashville (Robert Altman, 75)

11) Manhattan (Woody Allen, 79)

12) Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 79)

13) Aguirre The Wrath of God (Werner Herzog, 72 (Germany))

14) Deliverance (John Boorman, 72)

15) Network (Sidney Lumet, 76)

16) Gimme Shelter (Albert Maysles, David Maysles, Charlotte Zwerlin, 71)

17) One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest (Milos Forman, 75)

18) The Day of the Locust (John Schlesinger, 75)

19) O Lucky Man! (Lindsay Anderson, 73 (Britain))

20) Seven Beauties (Lina Wertmuller, 76 (Italy))

21) Breaking Away (Peter Yates, 79)

22) Best Boy (Ira Wohl, 79)

23) Barry Lyndon (Stanley Kubrick, 75 (Britain))

24) M.A.S.H. (Robert Altman, 70)

25) Punishment Park (Peter Watkins, 71 (Britain))

26) Badlands (Terrence Malick, 73)

27) McCabe and Mrs. Miller (Robert Altman, 71)

28) Dog Day Afternoon (Sidney Lumet, 76)

29) The Deer Hunter (Michael Cimino, 78)

30) The Outlaw Josey Wales (Clint Eastwood, 76)

31) Oblomov (Nikita Mikhalov, 79 (Russia))

32) Small Change (Francois Truffaut, 76 (France))

33) American Graffiti (George Lucas, 73)

34) Mean Streets (Martin Scorsese, 73)

35) Claire’s Knee (Eric Rohmer, 71 (France))

36) The Tin Drum (Volker Schlondorff, 79 (Germany))

37) Alien (Ridley Scott, 79)

38) All The President’s Men (Alan J. Pakula, 76)

39) The Black Stallion (Carroll Ballard, 79)

40) Being There (Hal Ashby, 79)

41) The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 74)

42) Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Steven Spielberg, 77)

43) The Honeymoon Killers (Leonard Kastle, 70)

44) Straight Time (Ulu Grosbard, 78)

45) Paper Moon (Peter Bogdanovich, 74)

46) The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 73)

47) Young Frankenstein (Mel Brooks, 74)

48) Special Delivery (John Weldon and Eunice MacCauley, 78)

49) A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 71 (Britain))

50) The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 74)

51) Images (Robert Altman, 72)

52) Tommy (Ken Russell, 75 (Britain))

53) Interiors (Woody Allen, 78)

54) A Woman Under the Influence (John Cassavetes, 74)

55) The Last Waltz (Martin Scorsese, 78)

56) Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 71)

57) Five Easy Pieces (Bob Rafelson, 71)

58) Harold and Maude (Hal Ashby, 71)

59) An Unmarried Woman (Paul Mazursky, 78)

60) Grey Gardens (Maysles/Hovde/Maysles/Meyer, 75)

61) Scenes from a Marriage (Ingmar Bergman, 76 (Sweden))

62) Halloween (John Carpenter, 78)

63) The Candidate (Michael Richie, 72)

64) Picnic at Hanging Rock (Peter Weir, 75 (Australia))

65) Dawn of the Dead (George A. Romero, 79)

66) Husbands (John Cassavetes, 70)

67) The Parallax View (Alan J. Pakula, 74)

68) Carnal Knowledge (Mike Nichols, 71)

70) Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky, 72 (Russia))

71) 3 Women (Robert Altman, 77)

72) Gates of Heaven (Errol Morris, 78)

73) Over The Edge (Jonathan Kaplan, 79)

74) F for Fake (Orson Welles, 74)

75) Frank Film (Frank Mouris, 73)

76) Kramer Vs. Kramer (Robert Benton, 79)

77) Electra Glide in Blue (James William Guercio, 73)

78) THX-1138 (Director’s Cut) (George Lucas, 71/2001)

79) The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (Luis Bunuel, 72 (Spain))

80) Harry and Tonto (Paul Mazursky, 74)

81) Monty Python and the Holy Grail (Jones/Gilliam, 75 (Britain))

82) Two-Lane Blacktop (Monte Hellman, 71)

83) Who’ll Stop The Rain? (Karel Reitz, 78)

84) Fiddler on the Roof (Norman Jewison, 71)

85) The Bad News Bears (Michael Richie, 76)

86) Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 75)

87) The Poseidon Adventure (Ronald Neame, 72)

88) What's Up Doc? (Peter Bogdanovich, 72)

89) The Man Who Would Be King (John Huston, 75)

90) Citizen’s Band / Handle With Care (Jonathan Demme, 77)

91) Ryan’s Daughter (David Lean, 70 (Britain))

92) Night Moves (Arthur Penn, 75)

93) The Silent Partner (Darryl Dukes, 79)

94) Edvard Munch (Peter Watkins, 74 (Britain/Norway))

95) The Front (Martin Ritt, 76)

96) Richard Pryor Live in Concert (Jeff Margolin, 79)

97) Bad Company (Robert Benton, 72)

98) Going in Style (Martin Brest, 79)

99) Wanda (Barbara Loden, 70)

100) Blazing Saddles (Mel Brooks, 74)

101) Sorcerer (William Friedkin, 78)

Monday, June 8, 2009

MASTER LIST #12: The 40 Best Film Books

In responding enthusiastically to MovieMan's wildfire-like Reading the Movies meme over at The Dancing Image, I've come up with my top forty movie books. Listed roughly in order of importance, they are as such (and I've recently added notations where I gather these books are OUT OF PRINT and thus need special pursuit):

1) The Cult Movies series (1,2, & 3) by Danny Peary (Delta 1981, 1984, 1989)

1) The Cult Movies series (1,2, & 3) by Danny Peary (Delta 1981, 1984, 1989)

2) Guide for the Film Fanatic by Danny Peary (Simon and Schuster, LTD, 1987)

3) Alternate Oscars by Danny Peary (Delta 1993)

For my money, Peary is the finest film writer out there. He transmits passion, knowledge and originality of thinking without ever becoming pretentious or unintelligible. He's funny, engaging, and has seen a whole lotta stuff. He's obviously an authority that deserves to be read again and again--and with his breezy style, it's easy to do so. The Cult Movies books are the best-looking non-color film books out there, too--each of the series' 200 entries come complete with credits, full synopses, 5 or so pages of analysis, and a few well-chosen photos; the movies he chooses to cover come from all genres and eras (Peary is a truly democratic film writer). Guide for the Film Fanatic is the book I run to before or after I've seen something notable; I must have burned through four copies of the tome over the years. And Alternate Oscars does brilliantly what we'd all like to do: mete out justice to the movies and actors that deserved the awards; his choices here are sometimes unfailingly personal, but the author always makes convincing arguments. He's now concentrating on sports writing but as a movie aficionado, Danny Peary is the best! No contest! (all are out of print)

4) Kiss Kiss Bang Bang by Pauline Kael (Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd, 1970)

5) Taking It All In by Pauline Kael (Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd, 1986))

6) 5001 Nights at the Movies by Pauline Kael (Holt Paperbacks, 1991)

I could list many more works by this legend, but I kept it down to these three--the first two were my teenaged introduction to the former New Yorker film writer, and the latter is the three-inch-thick guide to movies that also, to this day, is a regular reading stop for me. Kael often disappoints me with what she thinks of my favorite movies (she called 2001 "the biggest amateur movie ever made"), but her writing is so hard-scrabble vivid that I can forgive her 1000 times over for making me feel like a fool (though her opinions have rarely changed my mind). My circa-1989 NYC roommate Gary Sherwood once received a call from her in response to a letter he wrote regarding her favorable review of Tim Burton's Batman; through him, she asked me what my favorite movie thus far of 1989 was, and I responded sex, lies and videotape. She was not pleased, but I still love Soderburgh's movie. And, may I say, it's held up better than Burton's bloated epic has.

I could list many more works by this legend, but I kept it down to these three--the first two were my teenaged introduction to the former New Yorker film writer, and the latter is the three-inch-thick guide to movies that also, to this day, is a regular reading stop for me. Kael often disappoints me with what she thinks of my favorite movies (she called 2001 "the biggest amateur movie ever made"), but her writing is so hard-scrabble vivid that I can forgive her 1000 times over for making me feel like a fool (though her opinions have rarely changed my mind). My circa-1989 NYC roommate Gary Sherwood once received a call from her in response to a letter he wrote regarding her favorable review of Tim Burton's Batman; through him, she asked me what my favorite movie thus far of 1989 was, and I responded sex, lies and videotape. She was not pleased, but I still love Soderburgh's movie. And, may I say, it's held up better than Burton's bloated epic has.

7) The Stanley Kubrick Archives by Alison Castle (TASCHEN America Llc, 2008)

The mindbending publishing company Taschen released this massive $200 look into Stanley Kubrick's purview in 2008, and it promptly took first place status in the Kubrick book sweepstakes. Its overwhelming first half consists of frame blowups of images from each of Kubrick's works, from Killer's Kiss to Eyes Wide Shut (the source being Kubrick's prints of his own movies). And the extremely exacting latter half covers the ins and outs of each film's making, replete with Kubrick script pages, memos, and photographs. The book even covers his short films, his little-seen first feature Fear and Desire, his early photographic output for high school and Look magazine, and failed projects Napoleon, The Aryan Papers, and A.I. Stunningly designed and colored, this would be my choice for the nicest-looking, most revealing film book available. I note, happily, that my copy is signed by Malcolm McDowell on the full-page repro of his first Clockwork Orange close-up

8) Hitchcock/Truffaut by Francois Truffaut (Simon and Schuster - Touchstone Books, 1967)

8) Hitchcock/Truffaut by Francois Truffaut (Simon and Schuster - Touchstone Books, 1967)

The ultimate in classic conversation between fine filmmakers. Its revelatory quality is absolutely unmatched.

9) Inside Oscar (10th Anniversary Edition) and Inside Oscar 2 by Damien Bona and Mason Wiley (Ballantine Books 1996; Ballantine Books 2002)

An apologetically reverent look at film history, as seen through each year's politically-driven race for the Academy Awards. You'd think it'd be an easy thing to list all the conglomeration's nominees and winners, as this book does perfectly in its final section, but so many Oscar books screw things up with typos and just-plain-wrong information. Not this one. Inside Oscar is the definitive Academy Award overview. (out of print)

10) Joe Bob Goes To The Drive-In by Joe Bob Briggs (Delacorte Press 1986/1987, with intro by Stephen King)

Joe Bob (aka John Bloom) brings his unbridled joy to the discussion of bad (and good) filmmaking. His chunky, without-boundaries film writing reminds us of why we like movies: it's cuz they're fun. You know...fun? Remember that? It was on the basis of this book that I chimed in with my bosses at TNT in the mid-90s in recommending him as the host of that network's memorable Monstervision franchise. I'm not bragging--I'm just sayin'... (out of print)

11) This is Orson Welles by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (Harper Collins 1992)

Reading this, one realizes that Welles' reward as a cinematic genius wasn't necessarily in the making of often (but not always) great movies, but rather in the living of an always rich life. If we could have an earthly existence that held 1/1000th of the excitement that Orson felt, we'd be very lucky indeed.

12) Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of a New Hollywood by Mark Harris (Penguin (Non-Classics), 2009)

The best film book of recent years takes a gander at the five movies nominated for Best Picture at the 1967 Oscars: Bonnie and Clyde, Doctor Doolittle, The Graduate, Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, and In The Heat of the Night. Harris follows the gestation of these movies right up to their release and acclaim (or lack thereof). In doing so, he chronicles the late 60s seachange that led to the last golden era of movies, the 1970s. It reads like a masterful suspense novel--that's how engrossing it is.

13) Making Movies by Sidney Lumet (Vintage, 1996)

This is one book that deserves to rank as the future's #1 textbook for budding filmmakers. Lumet's attention to detail even extends to the direction of extras (he rightfully says that NYC extras are better than LA extras, because the NYC participants are real actors rather than fame-seeking hot-doggers). It's an extraordinary late-career contribution to film writing from one of cinema's greatest craftsmen.

14) The Making of Kubrick's 2001 by Jerome Agel (Signet; First Edition 1970)

14) The Making of Kubrick's 2001 by Jerome Agel (Signet; First Edition 1970)

I've had a copy of this book on my person ever since I saw 2001 when I was 11 (in 1977). I've only ever seen it as a pocket paperback, but it was clearly printed a lot, because I've never had any trouble finding a copy after my last one had fallen apart. Agel was a nimble media writer who'd worked closely with Marshall McLuhan on a number of tiny-but-dense paperbacks like The Medium is the Massage and Is Tomorrow Today? It's not surprising, but is nonetheless a miracle that he devoted time to compiling this incredible overview of one clearly groundbreaking movie. An Agel book is unmistakable in it layout, typeface, and bouncy form of organization. Here, along with that unique print voice, you will find numerous Kubrick interviews, talks with almost everyone associated with the film, critical reactions (often printed in full), fan (and non-fan) reactions, film quotes, and an amazing 96-page photo compilation that features cut scenes, behind-the-camera views, and frame blowups, all meticulously captioned. The best book ever produced dealing with a single title. (WAY out of print)

15) The Ingmar Bergman Archives by Paul Duncan and Bengt Wanselius (TASCHEN America Llc; Har/DVD/Fl edition 2008)

Like its Kubrick-centric predecessor, Taschen's richly illustrated analysis of the great Swedish filmmaker's career is essential to our understanding of Bergman's immutable worth.

16) RE/Search #10: Incredibly Strange Films by Vivian Vale and Andrea Juno (RE/Search, 1986)

16) RE/Search #10: Incredibly Strange Films by Vivian Vale and Andrea Juno (RE/Search, 1986)

The idiosyncratic San Francisco publishing company RE/Search threw into the film book race with this loving look at outside-the-mainstream filmmakers like Russ Meyer, Ted V. Mikels, Doris Wishman, Larry Cohen, Dave Friedman, Hershell Gordon Lewis, and Ray Dennis Steckler. A compilation of interviews and essays, as well as rare photos and movie ads, it's essential reading for filmfans looking for something different. (out of print)

17) Hollywood on the Riviera: The Inside Story of the Cannes Film Festival by Cari Beauchamp and Henri Behar (William Morrow & Co; 1992)

There've been scads of books written about the Oscars. But only one has been penned about the equally (if not more so) political machinations surrounding the world's leading film festival. This is that unmatchable book. (out of print)

18) The Motion Picture Guide by Stanley Ralph Ross and Jay Robert Nash (CineBooks, 1983)

In 1983, L.A. actors/writers Ross and Nash released this photo-less 17-volume set which examines, apparently, every movie ever made. Pre-IMDB, it was the go-to spot in learning the participants in any film you could think of. What was Peter Lorre's character's name in Beat The Devil? Who photographed Heaven With A Gun? Who wrote A Hatful of Rain? And what songs were used in American Graffiti? You could find the answers here. WARNING: the authors often synopsize the greatest movies in rash detail (their entry for Gone With the Wind lasts five pages, and that's in incredibly tiny type), so if you are sensitive to spoilers, don't read everything. And, I must say, my opinions of movies don't often jibe with theirs (they give Taxi Driver a half a star--they clearly like older movies). But, even if these guys sometimes seem as if they don't know what they're talking about, The Motion Picture Guide is a still a breathtaking achievement. The authors continued with yearly annuals until the 1990s, when they were replaced by Edmond Grant and Ken Fox. (WAY out of print)

19) Scorsese on Scorsese by David Thomson (Faber and Faber, 1989)

Another completist overview of a great filmmaker's career, told with utter honesty by the man himself. Regularly updated.

20) Reel Facts by Cobbett Steinberg (Penguin Books LTD; Rev Ed edition, 1981)

Reel Facts was a book that I picked up in an early edition when I was 10, in 1976. It clued this kid in to all major film festival and critics groups awards. There have been other books that have done what it does (including the later-cited The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards by Michael Gebert), but Steinberg's book is the only one that generously includes, in full, 35 years of the Harvard Lampoon's hilarious worst-movie awards (which takes up, thankfully, about 70 of 500-plus pages). (WAY out of print)

21) The Whole Equation: A History of Hollywood by David Thomson (Little, Brown; 2005)

A dazzling, and essentially personal view of film history that takes into account budgets, box-office, executive predilictions, decade zeitgeists, and filmic quality. It boggles the mind, really, in terms of its pervasive overview, and deserves to be a textbook mainstay.

22) In The Blink of an Eye by Walter Murch (Silman-James Press; 2 Revised edition, 2001)

The essential tome on film editing and sound work, written by a master of the crafts.

23) The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968 by Andrew Sarris (Da Capo Press, 1969)

The immutable 60s classic that first posited the auteur theory.

24) A Short History of the Movies by Bruce Kawin and Gerald Mast (Longman; 9th edition, 2005)

The eternal movie textbook, detailed and loving.

25) 50 Years of the Academy Awards (1977 edition) by Robert Osborne (Abbeville Press, 1977)

I got this 1977 book for Christmas that year, and its no-nonsense style, plus its copious illustrations, spurred me on to examine all major Oscar players. It's been updated repeatedly by the distinguished TCM host--up to the 80th year of the awards--but I have a fondness for this edition, particularly. (out of print)

26) Horror Movies: Tales of Terror in the Cinema by Alan G. Frank (Book Sales, 1974)

26) Horror Movies: Tales of Terror in the Cinema by Alan G. Frank (Book Sales, 1974)

I received this book for Christmas in 1975. I was a horror movie fan and a regular reader of Forrest J. Ackerman's Famous Monsters of Filmland, but I had never seen anything like this British-based horror movie book decorated with scads of fascinating photos. It's out-of-print now, but it should be in the library of any self-respecting horror movie fan (along with the more complete Nightmare Movies: A Critical Guide to Horror Movies by Kim Newman, which just missed making my top 40). (out of print)

27) The Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film (Vols. 1 & 2) by Michael Weldon (Ballantine Books, 1983, 1994)

Weldon--the master viewer of B-Movies, and the editor of the absolutely essential Psychotronic magazine, weighs in on all fronts, with great humor, passion and precision.

28) Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide by Leonard Maltin et. al (2000 edition published by Signet on September 1, 1999; published yearly)

The perennial movie guide is difiicult to determine in origin. I seem to remember it appearing on bookshelves as early as 1976 (along with Steven Schafner's now-forgotten TV Movies). Staunchly mainstream, it's always does well for a quick look at a movie you're about to watch, but as years progress, older titles are deleted. So, beware...

29) Scenes from the City: Filmmaking in New York by James Sanders (Rizzoli, 2006)

This amazing volume focuses in on movies shot on the greatest soundstage in movie history: New York City. Wholly backed by the New York City Mayor's Office of Film and Television, it features a pleathora of fantastic behind-the-scenes photos of all your favorite NYC-shot movies, complete with exacting locations (the scene from Annie Hall you like? Filmed at 67th and 2nd). It's an incredible work that's as much a travel guide as film book.

30) Stanley Kubrick Directs by Alexander Walker (Harcourt Brace Co; 1972)

Originally published in the early 70s (and recently updated in the 90s in order to cover the director's entire career), this critical dissection of Kubrick's works comes from a close personal friend of the director. As a kid, I referred to this book--which had incredibly valuable frame blow-ups and Walker's rich insights--many, many times. Its pages are instant nostalgia.

31) Defining Moments in Movies: The Greatest Films, Stars, Scenes and Events that Made Movie Magic, edited by Chris Fujiwara (Cassell Illustrated, 2007)

31) Defining Moments in Movies: The Greatest Films, Stars, Scenes and Events that Made Movie Magic, edited by Chris Fujiwara (Cassell Illustrated, 2007)

The most recent book on my list reads like a printed version of the web's most impassioned blogposts. Through the words of over 100 internationally-reknowned film writers, it recounts the major moments in film history, from 1899 to 2007. Beautifully illustrated and written, it makes me feel like an absolute dumbkopf--which I love, because I'm always looking to learn more. (out of print?)

32) Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho by Richard Anobile (Macmillan, 1974)

With this book, Anobile pioneered the now-dead fotonovel. He painstakingly looked at each of the key frames of Hitchcock's masterpiece and reproduced them in book form. This, of course, happened before each of us had VCRS and DVD players in our homes. So arriving into classrooms, as I once did with his books, was something of an achievement. He went on to do fotonovels for Ninotchka, Alien, Casablanca, The Maltese Falcon, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Dr. Jeckyl and Mr. Hyde, and Frankenstein, but Anobile's look at Psycho would remain his most valuable contribution to film publishing. (out of print)

33) Final Cut: Art, Money, and Ego in the Making of Heaven's Gate, the Film That Sank United Artists by Steven Bach (Newmarket Press; Revised edition, 1999)

Bach's unsparing look at Michael Cimino's studio-toppling making of Heaven's Gate--still, to me, a vastly underrated movie that popped up wrong-place-wrong-time--stands as a cautionary tale for young filmmakers who, tainted with a taste of success, think they can do anything under the sun.

34) Off-Hollywood Movies: A Film Lovers Guide by Richard Skorman (Harmony, 1989)

A guilty pleasure. The writing isn't notably superb, but the films cited are. (out of print)

35) The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards by Michael Gebert (St. Martins Mass Market Paper, 1996)

Gebart's vastly personal take on the history of movie awards is too vehement to be ignored. A great pocket-sized book to carry with you anywhere, if you're a movie lover. But I wish it were more complete, and twice as thick. (out of print)

36) Hollywood Rock, edited by Marshall Crenshaw and Ted Mico (Harper Collins; 1994)

The history of rock n' roll and all other related music genres, via movies. Crenshaw does little writing here, but his editing is unparalleled. If you like movies AND music--as I suspect many movie writers do--this is essential perusing. (out of print)

37) The Film Encyclopedia by Ephraim Katz (Collins; 6 edition, 2008)

The unquestionably ultimate source for biographical film information. Even in this age, it often trumps the IMDB for insanely accurate information about any film worker's career.

38) Film Forum: Thirty-Five Top Filmmakers Discuss Their Craft by Ellen Oumano (St Martins Press, 1985)

Godard, Altman, De Palma, Silver, and many more world filmmaker nitpick every single aspect of filmmaking in this singular hardback. A must. (out of print)

39) Directors in Action: Selections from Action, The Official Magazine of the Directors Guild of America by Bob Thomas (Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1973)

This very rare tome collects interviews with a bunch of forgotten (read: Paul Williams) and unforgotten (read: Hal Ashby and James Bridges) filmmakers, and really gets into the niggling details. A treasure. (WAY out of print)

40) Picture Shows: The Life and Films of Peter Bogdanovich by Andrew Yule (New York, NY Limelight Editions, 1992)

Only his close personal friend Orson Welles has come close to the life lived by this incredible moviemaker/film writer, who's made his way from print to Corman to filmmaking greatness to tragedy and The Sopranos in a remarkably colorful career. Though the book doesn't cover Bogdanovich's complete output, it does point to key decades radically experienced. (out of print)

I should note that I love the writings of J. Hoberman and Roger Ebert, but I've relied on their daily writings rather than their books. And I'm ashamed to say: I've read little by James Agee. Gotta get on that!

1) The Cult Movies series (1,2, & 3) by Danny Peary (Delta 1981, 1984, 1989)

1) The Cult Movies series (1,2, & 3) by Danny Peary (Delta 1981, 1984, 1989)2) Guide for the Film Fanatic by Danny Peary (Simon and Schuster, LTD, 1987)

3) Alternate Oscars by Danny Peary (Delta 1993)

For my money, Peary is the finest film writer out there. He transmits passion, knowledge and originality of thinking without ever becoming pretentious or unintelligible. He's funny, engaging, and has seen a whole lotta stuff. He's obviously an authority that deserves to be read again and again--and with his breezy style, it's easy to do so. The Cult Movies books are the best-looking non-color film books out there, too--each of the series' 200 entries come complete with credits, full synopses, 5 or so pages of analysis, and a few well-chosen photos; the movies he chooses to cover come from all genres and eras (Peary is a truly democratic film writer). Guide for the Film Fanatic is the book I run to before or after I've seen something notable; I must have burned through four copies of the tome over the years. And Alternate Oscars does brilliantly what we'd all like to do: mete out justice to the movies and actors that deserved the awards; his choices here are sometimes unfailingly personal, but the author always makes convincing arguments. He's now concentrating on sports writing but as a movie aficionado, Danny Peary is the best! No contest! (all are out of print)

4) Kiss Kiss Bang Bang by Pauline Kael (Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd, 1970)

5) Taking It All In by Pauline Kael (Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd, 1986))

6) 5001 Nights at the Movies by Pauline Kael (Holt Paperbacks, 1991)

I could list many more works by this legend, but I kept it down to these three--the first two were my teenaged introduction to the former New Yorker film writer, and the latter is the three-inch-thick guide to movies that also, to this day, is a regular reading stop for me. Kael often disappoints me with what she thinks of my favorite movies (she called 2001 "the biggest amateur movie ever made"), but her writing is so hard-scrabble vivid that I can forgive her 1000 times over for making me feel like a fool (though her opinions have rarely changed my mind). My circa-1989 NYC roommate Gary Sherwood once received a call from her in response to a letter he wrote regarding her favorable review of Tim Burton's Batman; through him, she asked me what my favorite movie thus far of 1989 was, and I responded sex, lies and videotape. She was not pleased, but I still love Soderburgh's movie. And, may I say, it's held up better than Burton's bloated epic has.

I could list many more works by this legend, but I kept it down to these three--the first two were my teenaged introduction to the former New Yorker film writer, and the latter is the three-inch-thick guide to movies that also, to this day, is a regular reading stop for me. Kael often disappoints me with what she thinks of my favorite movies (she called 2001 "the biggest amateur movie ever made"), but her writing is so hard-scrabble vivid that I can forgive her 1000 times over for making me feel like a fool (though her opinions have rarely changed my mind). My circa-1989 NYC roommate Gary Sherwood once received a call from her in response to a letter he wrote regarding her favorable review of Tim Burton's Batman; through him, she asked me what my favorite movie thus far of 1989 was, and I responded sex, lies and videotape. She was not pleased, but I still love Soderburgh's movie. And, may I say, it's held up better than Burton's bloated epic has.The mindbending publishing company Taschen released this massive $200 look into Stanley Kubrick's purview in 2008, and it promptly took first place status in the Kubrick book sweepstakes. Its overwhelming first half consists of frame blowups of images from each of Kubrick's works, from Killer's Kiss to Eyes Wide Shut (the source being Kubrick's prints of his own movies). And the extremely exacting latter half covers the ins and outs of each film's making, replete with Kubrick script pages, memos, and photographs. The book even covers his short films, his little-seen first feature Fear and Desire, his early photographic output for high school and Look magazine, and failed projects Napoleon, The Aryan Papers, and A.I. Stunningly designed and colored, this would be my choice for the nicest-looking, most revealing film book available. I note, happily, that my copy is signed by Malcolm McDowell on the full-page repro of his first Clockwork Orange close-up

8) Hitchcock/Truffaut by Francois Truffaut (Simon and Schuster - Touchstone Books, 1967)

8) Hitchcock/Truffaut by Francois Truffaut (Simon and Schuster - Touchstone Books, 1967)The ultimate in classic conversation between fine filmmakers. Its revelatory quality is absolutely unmatched.

9) Inside Oscar (10th Anniversary Edition) and Inside Oscar 2 by Damien Bona and Mason Wiley (Ballantine Books 1996; Ballantine Books 2002)

An apologetically reverent look at film history, as seen through each year's politically-driven race for the Academy Awards. You'd think it'd be an easy thing to list all the conglomeration's nominees and winners, as this book does perfectly in its final section, but so many Oscar books screw things up with typos and just-plain-wrong information. Not this one. Inside Oscar is the definitive Academy Award overview. (out of print)

10) Joe Bob Goes To The Drive-In by Joe Bob Briggs (Delacorte Press 1986/1987, with intro by Stephen King)

Joe Bob (aka John Bloom) brings his unbridled joy to the discussion of bad (and good) filmmaking. His chunky, without-boundaries film writing reminds us of why we like movies: it's cuz they're fun. You know...fun? Remember that? It was on the basis of this book that I chimed in with my bosses at TNT in the mid-90s in recommending him as the host of that network's memorable Monstervision franchise. I'm not bragging--I'm just sayin'... (out of print)

11) This is Orson Welles by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (Harper Collins 1992)

Reading this, one realizes that Welles' reward as a cinematic genius wasn't necessarily in the making of often (but not always) great movies, but rather in the living of an always rich life. If we could have an earthly existence that held 1/1000th of the excitement that Orson felt, we'd be very lucky indeed.

12) Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of a New Hollywood by Mark Harris (Penguin (Non-Classics), 2009)

The best film book of recent years takes a gander at the five movies nominated for Best Picture at the 1967 Oscars: Bonnie and Clyde, Doctor Doolittle, The Graduate, Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, and In The Heat of the Night. Harris follows the gestation of these movies right up to their release and acclaim (or lack thereof). In doing so, he chronicles the late 60s seachange that led to the last golden era of movies, the 1970s. It reads like a masterful suspense novel--that's how engrossing it is.

13) Making Movies by Sidney Lumet (Vintage, 1996)

This is one book that deserves to rank as the future's #1 textbook for budding filmmakers. Lumet's attention to detail even extends to the direction of extras (he rightfully says that NYC extras are better than LA extras, because the NYC participants are real actors rather than fame-seeking hot-doggers). It's an extraordinary late-career contribution to film writing from one of cinema's greatest craftsmen.

14) The Making of Kubrick's 2001 by Jerome Agel (Signet; First Edition 1970)

14) The Making of Kubrick's 2001 by Jerome Agel (Signet; First Edition 1970)I've had a copy of this book on my person ever since I saw 2001 when I was 11 (in 1977). I've only ever seen it as a pocket paperback, but it was clearly printed a lot, because I've never had any trouble finding a copy after my last one had fallen apart. Agel was a nimble media writer who'd worked closely with Marshall McLuhan on a number of tiny-but-dense paperbacks like The Medium is the Massage and Is Tomorrow Today? It's not surprising, but is nonetheless a miracle that he devoted time to compiling this incredible overview of one clearly groundbreaking movie. An Agel book is unmistakable in it layout, typeface, and bouncy form of organization. Here, along with that unique print voice, you will find numerous Kubrick interviews, talks with almost everyone associated with the film, critical reactions (often printed in full), fan (and non-fan) reactions, film quotes, and an amazing 96-page photo compilation that features cut scenes, behind-the-camera views, and frame blowups, all meticulously captioned. The best book ever produced dealing with a single title. (WAY out of print)

15) The Ingmar Bergman Archives by Paul Duncan and Bengt Wanselius (TASCHEN America Llc; Har/DVD/Fl edition 2008)

Like its Kubrick-centric predecessor, Taschen's richly illustrated analysis of the great Swedish filmmaker's career is essential to our understanding of Bergman's immutable worth.

16) RE/Search #10: Incredibly Strange Films by Vivian Vale and Andrea Juno (RE/Search, 1986)

16) RE/Search #10: Incredibly Strange Films by Vivian Vale and Andrea Juno (RE/Search, 1986)The idiosyncratic San Francisco publishing company RE/Search threw into the film book race with this loving look at outside-the-mainstream filmmakers like Russ Meyer, Ted V. Mikels, Doris Wishman, Larry Cohen, Dave Friedman, Hershell Gordon Lewis, and Ray Dennis Steckler. A compilation of interviews and essays, as well as rare photos and movie ads, it's essential reading for filmfans looking for something different. (out of print)

17) Hollywood on the Riviera: The Inside Story of the Cannes Film Festival by Cari Beauchamp and Henri Behar (William Morrow & Co; 1992)

There've been scads of books written about the Oscars. But only one has been penned about the equally (if not more so) political machinations surrounding the world's leading film festival. This is that unmatchable book. (out of print)

18) The Motion Picture Guide by Stanley Ralph Ross and Jay Robert Nash (CineBooks, 1983)

In 1983, L.A. actors/writers Ross and Nash released this photo-less 17-volume set which examines, apparently, every movie ever made. Pre-IMDB, it was the go-to spot in learning the participants in any film you could think of. What was Peter Lorre's character's name in Beat The Devil? Who photographed Heaven With A Gun? Who wrote A Hatful of Rain? And what songs were used in American Graffiti? You could find the answers here. WARNING: the authors often synopsize the greatest movies in rash detail (their entry for Gone With the Wind lasts five pages, and that's in incredibly tiny type), so if you are sensitive to spoilers, don't read everything. And, I must say, my opinions of movies don't often jibe with theirs (they give Taxi Driver a half a star--they clearly like older movies). But, even if these guys sometimes seem as if they don't know what they're talking about, The Motion Picture Guide is a still a breathtaking achievement. The authors continued with yearly annuals until the 1990s, when they were replaced by Edmond Grant and Ken Fox. (WAY out of print)

19) Scorsese on Scorsese by David Thomson (Faber and Faber, 1989)

Another completist overview of a great filmmaker's career, told with utter honesty by the man himself. Regularly updated.

20) Reel Facts by Cobbett Steinberg (Penguin Books LTD; Rev Ed edition, 1981)

Reel Facts was a book that I picked up in an early edition when I was 10, in 1976. It clued this kid in to all major film festival and critics groups awards. There have been other books that have done what it does (including the later-cited The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards by Michael Gebert), but Steinberg's book is the only one that generously includes, in full, 35 years of the Harvard Lampoon's hilarious worst-movie awards (which takes up, thankfully, about 70 of 500-plus pages). (WAY out of print)

21) The Whole Equation: A History of Hollywood by David Thomson (Little, Brown; 2005)

A dazzling, and essentially personal view of film history that takes into account budgets, box-office, executive predilictions, decade zeitgeists, and filmic quality. It boggles the mind, really, in terms of its pervasive overview, and deserves to be a textbook mainstay.

22) In The Blink of an Eye by Walter Murch (Silman-James Press; 2 Revised edition, 2001)

The essential tome on film editing and sound work, written by a master of the crafts.

23) The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968 by Andrew Sarris (Da Capo Press, 1969)

The immutable 60s classic that first posited the auteur theory.

24) A Short History of the Movies by Bruce Kawin and Gerald Mast (Longman; 9th edition, 2005)

The eternal movie textbook, detailed and loving.

25) 50 Years of the Academy Awards (1977 edition) by Robert Osborne (Abbeville Press, 1977)

I got this 1977 book for Christmas that year, and its no-nonsense style, plus its copious illustrations, spurred me on to examine all major Oscar players. It's been updated repeatedly by the distinguished TCM host--up to the 80th year of the awards--but I have a fondness for this edition, particularly. (out of print)

26) Horror Movies: Tales of Terror in the Cinema by Alan G. Frank (Book Sales, 1974)

26) Horror Movies: Tales of Terror in the Cinema by Alan G. Frank (Book Sales, 1974)I received this book for Christmas in 1975. I was a horror movie fan and a regular reader of Forrest J. Ackerman's Famous Monsters of Filmland, but I had never seen anything like this British-based horror movie book decorated with scads of fascinating photos. It's out-of-print now, but it should be in the library of any self-respecting horror movie fan (along with the more complete Nightmare Movies: A Critical Guide to Horror Movies by Kim Newman, which just missed making my top 40). (out of print)

27) The Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film (Vols. 1 & 2) by Michael Weldon (Ballantine Books, 1983, 1994)

Weldon--the master viewer of B-Movies, and the editor of the absolutely essential Psychotronic magazine, weighs in on all fronts, with great humor, passion and precision.

28) Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide by Leonard Maltin et. al (2000 edition published by Signet on September 1, 1999; published yearly)

The perennial movie guide is difiicult to determine in origin. I seem to remember it appearing on bookshelves as early as 1976 (along with Steven Schafner's now-forgotten TV Movies). Staunchly mainstream, it's always does well for a quick look at a movie you're about to watch, but as years progress, older titles are deleted. So, beware...

29) Scenes from the City: Filmmaking in New York by James Sanders (Rizzoli, 2006)

This amazing volume focuses in on movies shot on the greatest soundstage in movie history: New York City. Wholly backed by the New York City Mayor's Office of Film and Television, it features a pleathora of fantastic behind-the-scenes photos of all your favorite NYC-shot movies, complete with exacting locations (the scene from Annie Hall you like? Filmed at 67th and 2nd). It's an incredible work that's as much a travel guide as film book.

30) Stanley Kubrick Directs by Alexander Walker (Harcourt Brace Co; 1972)

Originally published in the early 70s (and recently updated in the 90s in order to cover the director's entire career), this critical dissection of Kubrick's works comes from a close personal friend of the director. As a kid, I referred to this book--which had incredibly valuable frame blow-ups and Walker's rich insights--many, many times. Its pages are instant nostalgia.

31) Defining Moments in Movies: The Greatest Films, Stars, Scenes and Events that Made Movie Magic, edited by Chris Fujiwara (Cassell Illustrated, 2007)

31) Defining Moments in Movies: The Greatest Films, Stars, Scenes and Events that Made Movie Magic, edited by Chris Fujiwara (Cassell Illustrated, 2007)The most recent book on my list reads like a printed version of the web's most impassioned blogposts. Through the words of over 100 internationally-reknowned film writers, it recounts the major moments in film history, from 1899 to 2007. Beautifully illustrated and written, it makes me feel like an absolute dumbkopf--which I love, because I'm always looking to learn more. (out of print?)

32) Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho by Richard Anobile (Macmillan, 1974)

With this book, Anobile pioneered the now-dead fotonovel. He painstakingly looked at each of the key frames of Hitchcock's masterpiece and reproduced them in book form. This, of course, happened before each of us had VCRS and DVD players in our homes. So arriving into classrooms, as I once did with his books, was something of an achievement. He went on to do fotonovels for Ninotchka, Alien, Casablanca, The Maltese Falcon, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Dr. Jeckyl and Mr. Hyde, and Frankenstein, but Anobile's look at Psycho would remain his most valuable contribution to film publishing. (out of print)

33) Final Cut: Art, Money, and Ego in the Making of Heaven's Gate, the Film That Sank United Artists by Steven Bach (Newmarket Press; Revised edition, 1999)

Bach's unsparing look at Michael Cimino's studio-toppling making of Heaven's Gate--still, to me, a vastly underrated movie that popped up wrong-place-wrong-time--stands as a cautionary tale for young filmmakers who, tainted with a taste of success, think they can do anything under the sun.

34) Off-Hollywood Movies: A Film Lovers Guide by Richard Skorman (Harmony, 1989)

A guilty pleasure. The writing isn't notably superb, but the films cited are. (out of print)

35) The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards by Michael Gebert (St. Martins Mass Market Paper, 1996)

Gebart's vastly personal take on the history of movie awards is too vehement to be ignored. A great pocket-sized book to carry with you anywhere, if you're a movie lover. But I wish it were more complete, and twice as thick. (out of print)

36) Hollywood Rock, edited by Marshall Crenshaw and Ted Mico (Harper Collins; 1994)

The history of rock n' roll and all other related music genres, via movies. Crenshaw does little writing here, but his editing is unparalleled. If you like movies AND music--as I suspect many movie writers do--this is essential perusing. (out of print)

37) The Film Encyclopedia by Ephraim Katz (Collins; 6 edition, 2008)

The unquestionably ultimate source for biographical film information. Even in this age, it often trumps the IMDB for insanely accurate information about any film worker's career.

38) Film Forum: Thirty-Five Top Filmmakers Discuss Their Craft by Ellen Oumano (St Martins Press, 1985)

Godard, Altman, De Palma, Silver, and many more world filmmaker nitpick every single aspect of filmmaking in this singular hardback. A must. (out of print)

39) Directors in Action: Selections from Action, The Official Magazine of the Directors Guild of America by Bob Thomas (Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1973)

This very rare tome collects interviews with a bunch of forgotten (read: Paul Williams) and unforgotten (read: Hal Ashby and James Bridges) filmmakers, and really gets into the niggling details. A treasure. (WAY out of print)

40) Picture Shows: The Life and Films of Peter Bogdanovich by Andrew Yule (New York, NY Limelight Editions, 1992)

Only his close personal friend Orson Welles has come close to the life lived by this incredible moviemaker/film writer, who's made his way from print to Corman to filmmaking greatness to tragedy and The Sopranos in a remarkably colorful career. Though the book doesn't cover Bogdanovich's complete output, it does point to key decades radically experienced. (out of print)

I should note that I love the writings of J. Hoberman and Roger Ebert, but I've relied on their daily writings rather than their books. And I'm ashamed to say: I've read little by James Agee. Gotta get on that!

Saturday, June 6, 2009

Film #132: An American Werewolf in London

In the early 1980s, there were few American directors whose style was as crunchy as John Landis'. It's difficult to explain what I mean by the term "crunchy"--I just know it's the correct word to describe many of the movies Landis made from 1977 to 1992. The only times he failed us were with the unbearable Spies Like Us, the equally awful Sly Stallone vehicle Oscar and his merely bland but hugely costly episode for Twilight Zone: The Movie. But the period's good stuff far outweighs the bad: Kentucky Fried Movie, National Lampoon's Animal House, The Blues Brothers, An American Werewolf in London, Trading Places, Michael Jackson's Thriller, Into the Night, Three Amigos, Coming to America, and Innocent Blood. All are primo American comedies of the 1970s and 80s. Actually, along with Woody Allen, Mel Brooks, Albert Brooks and maybe Zucker/Abrams/Zucker (Airplane, Top Secret) and Ivan Reitman (Meatballs, Ghostbusters), he's one of the era's top comedy autuers. But, honestly, if we're to look closely at Landis' work, he's as much a director of musicals as comedies. Of course, Michael Jackson's Thriller is his purest musical, and now with the death of the King of Pop, it may be his most pored-over film. But then consider Otis Day (in real life, he's Lloyd Williams) and the Knights singing "Shama-Lama-Ding-Dong" and "Shout" in Animal House; James Brown rocking the cathedral, Aretha Franklin tearing apart her diner, and Ray Charles moving the crowds in The Blues Brothers; the tuneful Randy Newman numbers Steve Martin, Martin Short, and Chevy Chase perform in Three Amigos; and the energetic African dance number in Coming to America. With this, and the colorful music-based sequences in many of his other films (including American Werewolf), Landis is very much a musically-minded director.

Night, Three Amigos, Coming to America, and Innocent Blood. All are primo American comedies of the 1970s and 80s. Actually, along with Woody Allen, Mel Brooks, Albert Brooks and maybe Zucker/Abrams/Zucker (Airplane, Top Secret) and Ivan Reitman (Meatballs, Ghostbusters), he's one of the era's top comedy autuers. But, honestly, if we're to look closely at Landis' work, he's as much a director of musicals as comedies. Of course, Michael Jackson's Thriller is his purest musical, and now with the death of the King of Pop, it may be his most pored-over film. But then consider Otis Day (in real life, he's Lloyd Williams) and the Knights singing "Shama-Lama-Ding-Dong" and "Shout" in Animal House; James Brown rocking the cathedral, Aretha Franklin tearing apart her diner, and Ray Charles moving the crowds in The Blues Brothers; the tuneful Randy Newman numbers Steve Martin, Martin Short, and Chevy Chase perform in Three Amigos; and the energetic African dance number in Coming to America. With this, and the colorful music-based sequences in many of his other films (including American Werewolf), Landis is very much a musically-minded director.

I guess if I'm to look into my heart, the word "crunchy" really refers primarily to Landis' cutting methods. Whether working with editors George Folsey Jr. or Malcolm Campbell, his films always display the unmistakable branding of post-production expertise. Landis' editing, more so than that of most directors, has a palpably mathematical quality about it. It swiftly gets us in and out of scenes, often with a barely registered punchline or an extra shock to the system before we go. And it thrives on juxtaposing chaos with calm. Look at the insane ending to The Blues Brothers--that off-screen clicking of a hundred guns, and then we cut to that quiet shot of Jake and Elwood at the firing end of an impossibly well-placed number of gun barrels. Or look at Animal House, where we have all this wackiness ensuing outside and then we get a quick, calm look at Flounder (Stephen Furst) asking a store cashier "Can I have a thousand marbles, please?" Or how, right in the middle of the horrifying transformation scene in American Werewolf, Landis humorously cuts to a short insert of the scene's only witness: a grinning Mickey Mouse figurine.

There are a lot more moments like this in American Werewolf, a movie that registers as Landis' best. It's funny, but it's also extremely terrifying--often very much in the same frame. Length-wise, at 97 minutes, it's the director's most economical work (his movies tend to run a little longer than necessary). American Werewolf tells a simple story, effectively, and then gets right on out of there. With its dismaying final shot, and the bouncily-scored credit crawl that instantaneously follows it up, it's a movie that delightedly sucker-punches us and then darts laughing down the street. Perhaps American Werewolf's most surprising element is its sweetness. In fact, one could say that Landis movies often take us aback with moments of unexpected sentiment. My favorite scene in The Blues Brothers has Jake, recently released from prison, falling instantly asleep on Elwood's tenement bed. Elwood hollers "Hey, you sleaze! That's my bed." And then Elwood, glad to see his brother again, covers him up and continues cooking toast over a Sterno flame. And I'm always soothed by how much I adore the romantic elements in Animal House, Coming to America, and Trading Places. However, even within this pantheon, the connection enjoyed by the American Werewolf leads is really something special.

Perhaps American Werewolf's most surprising element is its sweetness. In fact, one could say that Landis movies often take us aback with moments of unexpected sentiment. My favorite scene in The Blues Brothers has Jake, recently released from prison, falling instantly asleep on Elwood's tenement bed. Elwood hollers "Hey, you sleaze! That's my bed." And then Elwood, glad to see his brother again, covers him up and continues cooking toast over a Sterno flame. And I'm always soothed by how much I adore the romantic elements in Animal House, Coming to America, and Trading Places. However, even within this pantheon, the connection enjoyed by the American Werewolf leads is really something special.

Former Dr. Pepper spokesman and star of ABC's disco-themed sitcom Makin' It David Naughton plays an average guy wandering through the British countryside with his best friend Jack (Griffin Dunne). They're first seen getting off a truck with a bunch of sheep on it ("Goodbye, girls!" Jack says as the truck pulls off). It's telling--thought the boys sadly don't get it--that the only establishment they spot to duck into is called The Slaughtered Lamb. Taking refuge from the cold moors, David and Jack instantly suss out that they're unwelcome outsiders here, particularly when they ask about the creepy pentagram painted on the walls. This stuns the rowdy crowd of British townies into silence, and the two friends feel prodded into escape (after they're gone, the pub's patrons argue about whether they should have insisted they stay, even though they DO warn them to keep to the roads).

It's after they start hearing pained howls underneath the light of a full moon that David and Jack notice they haven't stayed on the roads ("Oops," Jack says). In a sickening, disorienting sequence, the friends run round directionless for a few minutes before realizing they've been spotted by something (the camera eerily sets itself in front of them). And then the carnage begins. For a movie that's billed as a comedy, this scene--like many more that will follow it--is brutal and unsettling, and gamely lets the horror movie element take hold. (SPOILER ALERT!) Jack's death is sudden, bloody, and frantic. But David survives, passing out after the townies pump buckshot into this gigantic wolf that's attacked them.

David wakes up in a London hospital with Alex (Jenny Agutter) as his instantly smitten nurse. He is feverish and slashed up, and drifts in and out of fitful sleeps where he has some potent nightmares (these are some of the film's best scenes, and if you haven't seen it, I'll do you a favor by shutting up). David also starts getting visits from the dead and decaying Jack (to me, Rick Baker's oozing, meaty work on Dunne's once-pretty face is really what won him the Oscar, the first competitive one for makeup, in 1981). Jack pleads with David to off himself, to spare the lives of others he's bound to kill, because now he is a werewolf, and we all know what that means. But David thinks he's merely going crazy, and he doesn't take Jack's advise to heart. In fact, upon his release, David finds he has something more to live for when Alex saucily invites him to stay with her for a while. This sparks a relationship that's tender and sexy--we like these two people together--and this inclusion of a bit of heart in the story pays off later in unexpectedly touching ways. David Naughton only appeared in a few more forgettable movies after American Werewolf, but he makes an brave impression here as a complete innocent to whom fate has been unkind. This may be the best portrayal of a lycanthrope ever (his piercing screams during the demanding transformation scene--set incongruously to Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Bad Moon Rising"--convince us that turning into a werewolf is quite a bit more painful than the serene lap-dissolves we were once familiar with from movies like the Lon Chaney Jr. Wolf Man of the 1940s). Of course, Baker's work here is magnificent, and inventive (the close up of the hair sprouting from David's skin was achieved by pulling on the strands from behind the patch of flesh-like latex and then running the footage backwards). But it's Naughton's performance that terrifies us (I love it when, in mid-transformation, David's human side makes a final appearance when he apologizes to the dead Jack for calling him "a walking meat loaf").

David Naughton only appeared in a few more forgettable movies after American Werewolf, but he makes an brave impression here as a complete innocent to whom fate has been unkind. This may be the best portrayal of a lycanthrope ever (his piercing screams during the demanding transformation scene--set incongruously to Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Bad Moon Rising"--convince us that turning into a werewolf is quite a bit more painful than the serene lap-dissolves we were once familiar with from movies like the Lon Chaney Jr. Wolf Man of the 1940s). Of course, Baker's work here is magnificent, and inventive (the close up of the hair sprouting from David's skin was achieved by pulling on the strands from behind the patch of flesh-like latex and then running the footage backwards). But it's Naughton's performance that terrifies us (I love it when, in mid-transformation, David's human side makes a final appearance when he apologizes to the dead Jack for calling him "a walking meat loaf").  There are many amazing set pieces strewn about here: the stalking of a London businessman in a deserted tube station; the lovely, lathery shower David and Alex take together, set to Van Morrison's "Moondance"; the convention of the dead in a Leicester Square porno house (which plays a funny sex film called "See You Next Wednesday," a title phrase that's strangely appeared in numerous Landis movies); the aformentioned nightmares; the morning after, when David finds himself in the buff and penned up with a pack of wolves at the London Zoo (a scene that culminates with the immortal line "A naked American man stole my balloons"); and, perhaps most stultifying, the visceral car-crash chaos that erupts when the werewolf hits the busy British streets. These scenes, plus the perturbing, over-too-quick finale and the gorily amusing moments featuring the rapidly rotting Dunne (who should have gotten a Supporting Actor Oscar nomination), help insure An American Werewolf in London won't be sinking into obscurity any time soon.

There are many amazing set pieces strewn about here: the stalking of a London businessman in a deserted tube station; the lovely, lathery shower David and Alex take together, set to Van Morrison's "Moondance"; the convention of the dead in a Leicester Square porno house (which plays a funny sex film called "See You Next Wednesday," a title phrase that's strangely appeared in numerous Landis movies); the aformentioned nightmares; the morning after, when David finds himself in the buff and penned up with a pack of wolves at the London Zoo (a scene that culminates with the immortal line "A naked American man stole my balloons"); and, perhaps most stultifying, the visceral car-crash chaos that erupts when the werewolf hits the busy British streets. These scenes, plus the perturbing, over-too-quick finale and the gorily amusing moments featuring the rapidly rotting Dunne (who should have gotten a Supporting Actor Oscar nomination), help insure An American Werewolf in London won't be sinking into obscurity any time soon.

Night, Three Amigos, Coming to America, and Innocent Blood. All are primo American comedies of the 1970s and 80s. Actually, along with Woody Allen, Mel Brooks, Albert Brooks and maybe Zucker/Abrams/Zucker (Airplane, Top Secret) and Ivan Reitman (Meatballs, Ghostbusters), he's one of the era's top comedy autuers. But, honestly, if we're to look closely at Landis' work, he's as much a director of musicals as comedies. Of course, Michael Jackson's Thriller is his purest musical, and now with the death of the King of Pop, it may be his most pored-over film. But then consider Otis Day (in real life, he's Lloyd Williams) and the Knights singing "Shama-Lama-Ding-Dong" and "Shout" in Animal House; James Brown rocking the cathedral, Aretha Franklin tearing apart her diner, and Ray Charles moving the crowds in The Blues Brothers; the tuneful Randy Newman numbers Steve Martin, Martin Short, and Chevy Chase perform in Three Amigos; and the energetic African dance number in Coming to America. With this, and the colorful music-based sequences in many of his other films (including American Werewolf), Landis is very much a musically-minded director.

Night, Three Amigos, Coming to America, and Innocent Blood. All are primo American comedies of the 1970s and 80s. Actually, along with Woody Allen, Mel Brooks, Albert Brooks and maybe Zucker/Abrams/Zucker (Airplane, Top Secret) and Ivan Reitman (Meatballs, Ghostbusters), he's one of the era's top comedy autuers. But, honestly, if we're to look closely at Landis' work, he's as much a director of musicals as comedies. Of course, Michael Jackson's Thriller is his purest musical, and now with the death of the King of Pop, it may be his most pored-over film. But then consider Otis Day (in real life, he's Lloyd Williams) and the Knights singing "Shama-Lama-Ding-Dong" and "Shout" in Animal House; James Brown rocking the cathedral, Aretha Franklin tearing apart her diner, and Ray Charles moving the crowds in The Blues Brothers; the tuneful Randy Newman numbers Steve Martin, Martin Short, and Chevy Chase perform in Three Amigos; and the energetic African dance number in Coming to America. With this, and the colorful music-based sequences in many of his other films (including American Werewolf), Landis is very much a musically-minded director. I guess if I'm to look into my heart, the word "crunchy" really refers primarily to Landis' cutting methods. Whether working with editors George Folsey Jr. or Malcolm Campbell, his films always display the unmistakable branding of post-production expertise. Landis' editing, more so than that of most directors, has a palpably mathematical quality about it. It swiftly gets us in and out of scenes, often with a barely registered punchline or an extra shock to the system before we go. And it thrives on juxtaposing chaos with calm. Look at the insane ending to The Blues Brothers--that off-screen clicking of a hundred guns, and then we cut to that quiet shot of Jake and Elwood at the firing end of an impossibly well-placed number of gun barrels. Or look at Animal House, where we have all this wackiness ensuing outside and then we get a quick, calm look at Flounder (Stephen Furst) asking a store cashier "Can I have a thousand marbles, please?" Or how, right in the middle of the horrifying transformation scene in American Werewolf, Landis humorously cuts to a short insert of the scene's only witness: a grinning Mickey Mouse figurine.

There are a lot more moments like this in American Werewolf, a movie that registers as Landis' best. It's funny, but it's also extremely terrifying--often very much in the same frame. Length-wise, at 97 minutes, it's the director's most economical work (his movies tend to run a little longer than necessary). American Werewolf tells a simple story, effectively, and then gets right on out of there. With its dismaying final shot, and the bouncily-scored credit crawl that instantaneously follows it up, it's a movie that delightedly sucker-punches us and then darts laughing down the street.

Former Dr. Pepper spokesman and star of ABC's disco-themed sitcom Makin' It David Naughton plays an average guy wandering through the British countryside with his best friend Jack (Griffin Dunne). They're first seen getting off a truck with a bunch of sheep on it ("Goodbye, girls!" Jack says as the truck pulls off). It's telling--thought the boys sadly don't get it--that the only establishment they spot to duck into is called The Slaughtered Lamb. Taking refuge from the cold moors, David and Jack instantly suss out that they're unwelcome outsiders here, particularly when they ask about the creepy pentagram painted on the walls. This stuns the rowdy crowd of British townies into silence, and the two friends feel prodded into escape (after they're gone, the pub's patrons argue about whether they should have insisted they stay, even though they DO warn them to keep to the roads).

It's after they start hearing pained howls underneath the light of a full moon that David and Jack notice they haven't stayed on the roads ("Oops," Jack says). In a sickening, disorienting sequence, the friends run round directionless for a few minutes before realizing they've been spotted by something (the camera eerily sets itself in front of them). And then the carnage begins. For a movie that's billed as a comedy, this scene--like many more that will follow it--is brutal and unsettling, and gamely lets the horror movie element take hold. (SPOILER ALERT!) Jack's death is sudden, bloody, and frantic. But David survives, passing out after the townies pump buckshot into this gigantic wolf that's attacked them.

David wakes up in a London hospital with Alex (Jenny Agutter) as his instantly smitten nurse. He is feverish and slashed up, and drifts in and out of fitful sleeps where he has some potent nightmares (these are some of the film's best scenes, and if you haven't seen it, I'll do you a favor by shutting up). David also starts getting visits from the dead and decaying Jack (to me, Rick Baker's oozing, meaty work on Dunne's once-pretty face is really what won him the Oscar, the first competitive one for makeup, in 1981). Jack pleads with David to off himself, to spare the lives of others he's bound to kill, because now he is a werewolf, and we all know what that means. But David thinks he's merely going crazy, and he doesn't take Jack's advise to heart. In fact, upon his release, David finds he has something more to live for when Alex saucily invites him to stay with her for a while. This sparks a relationship that's tender and sexy--we like these two people together--and this inclusion of a bit of heart in the story pays off later in unexpectedly touching ways.

David Naughton only appeared in a few more forgettable movies after American Werewolf, but he makes an brave impression here as a complete innocent to whom fate has been unkind. This may be the best portrayal of a lycanthrope ever (his piercing screams during the demanding transformation scene--set incongruously to Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Bad Moon Rising"--convince us that turning into a werewolf is quite a bit more painful than the serene lap-dissolves we were once familiar with from movies like the Lon Chaney Jr. Wolf Man of the 1940s). Of course, Baker's work here is magnificent, and inventive (the close up of the hair sprouting from David's skin was achieved by pulling on the strands from behind the patch of flesh-like latex and then running the footage backwards). But it's Naughton's performance that terrifies us (I love it when, in mid-transformation, David's human side makes a final appearance when he apologizes to the dead Jack for calling him "a walking meat loaf").

David Naughton only appeared in a few more forgettable movies after American Werewolf, but he makes an brave impression here as a complete innocent to whom fate has been unkind. This may be the best portrayal of a lycanthrope ever (his piercing screams during the demanding transformation scene--set incongruously to Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Bad Moon Rising"--convince us that turning into a werewolf is quite a bit more painful than the serene lap-dissolves we were once familiar with from movies like the Lon Chaney Jr. Wolf Man of the 1940s). Of course, Baker's work here is magnificent, and inventive (the close up of the hair sprouting from David's skin was achieved by pulling on the strands from behind the patch of flesh-like latex and then running the footage backwards). But it's Naughton's performance that terrifies us (I love it when, in mid-transformation, David's human side makes a final appearance when he apologizes to the dead Jack for calling him "a walking meat loaf").  There are many amazing set pieces strewn about here: the stalking of a London businessman in a deserted tube station; the lovely, lathery shower David and Alex take together, set to Van Morrison's "Moondance"; the convention of the dead in a Leicester Square porno house (which plays a funny sex film called "See You Next Wednesday," a title phrase that's strangely appeared in numerous Landis movies); the aformentioned nightmares; the morning after, when David finds himself in the buff and penned up with a pack of wolves at the London Zoo (a scene that culminates with the immortal line "A naked American man stole my balloons"); and, perhaps most stultifying, the visceral car-crash chaos that erupts when the werewolf hits the busy British streets. These scenes, plus the perturbing, over-too-quick finale and the gorily amusing moments featuring the rapidly rotting Dunne (who should have gotten a Supporting Actor Oscar nomination), help insure An American Werewolf in London won't be sinking into obscurity any time soon.

There are many amazing set pieces strewn about here: the stalking of a London businessman in a deserted tube station; the lovely, lathery shower David and Alex take together, set to Van Morrison's "Moondance"; the convention of the dead in a Leicester Square porno house (which plays a funny sex film called "See You Next Wednesday," a title phrase that's strangely appeared in numerous Landis movies); the aformentioned nightmares; the morning after, when David finds himself in the buff and penned up with a pack of wolves at the London Zoo (a scene that culminates with the immortal line "A naked American man stole my balloons"); and, perhaps most stultifying, the visceral car-crash chaos that erupts when the werewolf hits the busy British streets. These scenes, plus the perturbing, over-too-quick finale and the gorily amusing moments featuring the rapidly rotting Dunne (who should have gotten a Supporting Actor Oscar nomination), help insure An American Werewolf in London won't be sinking into obscurity any time soon.

Thursday, June 4, 2009

Love Theme from Halloween (R.I.P. Patrick Flynn 1961-2009)

My very best friend Patrick Flynn passed away on May 20th, and as John Carpenter's Halloween was one of his favorite movies, I thought I'd write these bad-taste lyrics for Carpenter's eerie electronic theme for the movie. Hey, it's silly, but Patrick would have dug it. Thanks to Bill Tomey for the idea, and you can hear the theme below!

LOVE THEME FROM HALLOWEEN

(BACKGROUND MELODY)

Jab jab jab

Stab stab stab

Kill kill kill

Jab jab jab

Still I go and

Stalk stalk stalk

Walk walk walk

Die die die

Fall down and die

And get up again

Up again, up again, up again

Then I go after you

After you, after you, after you

You and those brats of yours

Brats of yours, brats of yours, brats of yours

Friends are total idiots

Idiots, idiots, idiots

They will feel my shiny blade

Shiny blade, shiny blade, shiny blade

Certainly the boogey man

boogey man, boogey man, boogey man

Glide around and

(repeat ad nauseum)

(MAIN MELODY)

Halloween night

Taste my fright

Run all night

Without light

Dropping the knife

Disbelieving

Always greiving

Finding friends dead

Headstone on bed

Donald Pleasence

Fancy presence

Scardy head shrink

while in the klink

But I'm free now

Wear a mask now

William Shatner

What's it matter?

Where's my sister?

How I missed her

Want to tell her

Stab and smell her

Jamie Lee, you're

Chaste and clean, you're

All I wanted

To send to hell on...

(repeat)

Wednesday, June 3, 2009

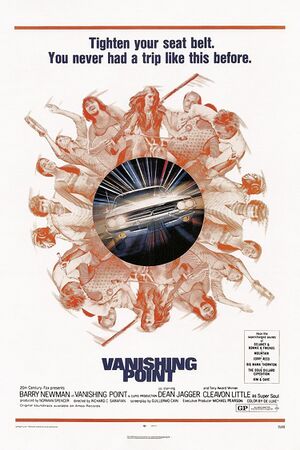

Film #131: Vanishing Point

With a plaintive, desert-baked guitar acting as soundtrack, Richard C. Sarafian's existential action epic Vanishing Point begins at its end, with rust-speckled bulldozers rumbling through the morning light of a funereal California town apparently populated only by doddering old men with ancient hats. As helicopters dot the air, these earth-movers situate themselves imposingly in Main Street's middle as a makeshift roadblock. They're the law's last stab at halting a determined, enigmatic force named Kowalski (Barry Newman), who's about to spend the rest of this melancholy, pepped-up movie muscling towards San Francisco in high-speed flashback.

With a plaintive, desert-baked guitar acting as soundtrack, Richard C. Sarafian's existential action epic Vanishing Point begins at its end, with rust-speckled bulldozers rumbling through the morning light of a funereal California town apparently populated only by doddering old men with ancient hats. As helicopters dot the air, these earth-movers situate themselves imposingly in Main Street's middle as a makeshift roadblock. They're the law's last stab at halting a determined, enigmatic force named Kowalski (Barry Newman), who's about to spend the rest of this melancholy, pepped-up movie muscling towards San Francisco in high-speed flashback.From the outset, Vanishing Point's then-retro framing and locale is a devoted tip of the brim to the western. After Peckinpah and Leone blew the genre up in the late 1960s, it had nowhere to go but here. Spotted palaminos were replicated by similarly-named cars--in this case, the key one being a blindingly white 1970 Dodge Challenger, piloted by a nearly empty-hearted, tow-headed Colorado cowboy who must deliver it to the California coastline in record time (as in Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch--a welcome influence--wide-eyed children are constantly documented as witnesses to the action). Jazzed by handfuls of Bennies, Kowalski is unshakingly single-minded and, like all great cowboys, has little to say about his task except through unfettered dash. His crotchety old boss admonishes him early on: "You're gonna kill yourself one day, do ya know?" "Yeah, I know" is Kowalski's tired reply.

Vanishing Point was one of the cinema's prime offerings to the drive-in gods in the 1970s. I must have sat in the back seat, with my parents up front, watching this adrenaline-pumper (often as a second feature) at least ten times that decade. I vividly remember it being paired often with another searching 1971 car movie, Monte Hellman's Two Lane Blacktop, and also in re-release as part of a much-touted 1974 20th-Century Fox-powered double bill with another key drive-in car-chase classic, Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry, starring Peter Fonda and Susan George (I can also recall its appearing with Floyd Mutrix's like-minded auto-centric romance Aloha Bobby and Rose). Watching Vanishing Point recently, I realized its immutable impact on me when, ten minutes in, Kowalski's speeding car is at once stopped in freeze-frame, and then disappears from the screen. Even as a kid, I thought: "What is THIS?!" In its own way, it's as indelible a moment as Truffaut's freeze-frame climax to The 400 Blows.

Vanishing Point was one of the cinema's prime offerings to the drive-in gods in the 1970s. I must have sat in the back seat, with my parents up front, watching this adrenaline-pumper (often as a second feature) at least ten times that decade. I vividly remember it being paired often with another searching 1971 car movie, Monte Hellman's Two Lane Blacktop, and also in re-release as part of a much-touted 1974 20th-Century Fox-powered double bill with another key drive-in car-chase classic, Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry, starring Peter Fonda and Susan George (I can also recall its appearing with Floyd Mutrix's like-minded auto-centric romance Aloha Bobby and Rose). Watching Vanishing Point recently, I realized its immutable impact on me when, ten minutes in, Kowalski's speeding car is at once stopped in freeze-frame, and then disappears from the screen. Even as a kid, I thought: "What is THIS?!" In its own way, it's as indelible a moment as Truffaut's freeze-frame climax to The 400 Blows.Kowalski's not a bad guy. He may be a bifurcated speed addict through and through, but he has a job to do and he does it well. Stodgy badge-wearers retreat to radios, roads and sky to keep the man from doing his chore, but they amount to little more than housefly-scaled irritants. Even with his lawlessness, Kowalski's careful to ensure the safety of the civilian and non-civilian drivers he deftly runs off the dusty western byways. Differently from the heroes of a host of 1970s films, this vigorous man--an unappreciated Vietnam vet and former racetrack loser--is always thoughtful regarding those he's bested. In return, the fates hand him the victory/homecoming he always desired. This character, in his most dire moment, gets assistance from Dean Jagger (the Supporting Actor Oscar-winnner for 1949's WWII saga Twelve O'Clock High, portrays a desert-wisened snake charmer who teaches Kowalski how to truly become invisible). Amidst this movie's screeching, dust-cloud bedlam--as with the whole of the clip-clopping western genre--one of the glitziest adornments to Vanishing Point is its portraiture of the rocky, brush-covered countryside, though here the boonies are slashed not by towering buttes, but by the horizontally-angular intrusion of asphalt and white lines.

Sarafian's studied camera is captained by cinematographer John A. Alonzo, who'd later extend his grainy, rarely-showy talent to classics like Harold and Maude, Sounder, Chinatown, The Bad News Bears, Norma Rae, Scarface and George Clooney's black-and-white live-TV remake of Fail Safe (2000). Alonzo broke through to the A-list with Vanishing Point and it's no mystery why: his agile camera keeps up with that raging Dodge Challenger like a battle-scarred trooper. It zooms in slightly, seemingly desirous to become one with the automobile's metallic body, spotting the white demon in long shot through the astral prism of the wavy desert heat, and then capturing it in disorienting, motion-filled close-ups as the sandy sunshine reflecting off Kowalski's windshield blinds us to this dude's actual motivations (the worst scene in the movie, which should have hit the post-production floor, mawkishly refers to Kowalski's seaside past with a long-haired blonde, who's mirrored often amongst the movie's few women; as it's inferred, she disappears in a surfing mishap). This thankfully brief moment--along with one involving an adoring, nude lady hog rider--confuses and bores the viewer, since we already know Kowalski's uber-practical aims. We don't need ladles of sentiment to satify here.