Remakes make me so angry. Let's take the redo of 1975's Rollerball. When one deigns to mention this, yes, over-the-top but still entertaining and meaningful film to people who don't know about IT, but DO know about John McTiernan's missed-the-whole-point, Razzie-nominated 2002 remake, you inevitably hear a groan. And then you have to explain "No, not that one---the GOOD one..." I must have wasted two hours of my life saying that phrase.

Remakes make me so angry. Let's take the redo of 1975's Rollerball. When one deigns to mention this, yes, over-the-top but still entertaining and meaningful film to people who don't know about IT, but DO know about John McTiernan's missed-the-whole-point, Razzie-nominated 2002 remake, you inevitably hear a groan. And then you have to explain "No, not that one---the GOOD one..." I must have wasted two hours of my life saying that phrase. Now that my rant is done, I can go on and rant about how much I love Norman Jewison's original film--it's a real memorable treat from my childhood, so I can't be swayed on this matter. Anyway, Jewison's an interesting director--the guy has done comedies (The Russians Are Coming The Russians Are Coming, Moonstruck, Best Friends), musicals (Jesus Christ Superstar, Fiddler on the Roof), mysteries (In The Heat of the Night, Agnes of God, A Soldier's Story), heavy dramas (The Hurricane, In Country), heist movies (The Thomas Crown Affair--sigh...THE ORIGINAL, withe Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway) and with Rollerball, science fiction. I can't say he has any discernible style as a filmmaker except in the choices he makes story-wise--all of his films have a certain "message," for lack of a better word--y'know, racism is bad, respect war veterans, understand each other, and so on. Sounds like I have a problem with that, but I don't; I like Jewison's liberalism. And I like that one never knows what to expect from his movies, except that they're going to be expertly produced (he often acts as his own producer, too).

With Rollerball, he sends us a stark missive about the savage quality of sports and its fans that, like Dr. Strangelove and Network, is coming more true with each passing year (cage match, anyone?). James Caan stars as Jonathan E., the reigning superstar of a future sport that combines roller derby, motorcross racing, football, basketball, and all-out warfare. This X-tremely gory pastime has in fact replaced warfare between nations by slaking the bloodthirst of its maniacal fan base. So this ongoing World Cup, with games between international cities, marches on with Jonathan as its poster boy. However, what Rollerball REALLY represents is not a battle between countries, but between the omnipotent corporate entities that own each franchise (here represented by John Houseman's blustery Mr. Bartholomew).

With Rollerball, he sends us a stark missive about the savage quality of sports and its fans that, like Dr. Strangelove and Network, is coming more true with each passing year (cage match, anyone?). James Caan stars as Jonathan E., the reigning superstar of a future sport that combines roller derby, motorcross racing, football, basketball, and all-out warfare. This X-tremely gory pastime has in fact replaced warfare between nations by slaking the bloodthirst of its maniacal fan base. So this ongoing World Cup, with games between international cities, marches on with Jonathan as its poster boy. However, what Rollerball REALLY represents is not a battle between countries, but between the omnipotent corporate entities that own each franchise (here represented by John Houseman's blustery Mr. Bartholomew). What this ultimately means is "There is no 'I' in 'team'." Jonathan and his mates aren't allowed a personality; their job is only to win at all costs. Problem is, Jonathan is becoming a little too famous. And his best friend, Moonpie (John Beck), is letting the Dallas team's Rollerball superiority go to his head. It's Moonpie's head, in fact, that gets needlessly cracked (at Houseman's go-ahead) after he insults his boss in the locker room. With his best friend now in a coma, Jonathan begins to see the wizard behind the curtain, and it feeds into his distaste for a game he used to love.

As a person who has always been at odds with the blind love of sports to which most seem to cling, I find Rollerball's anti-sports-violence stance not only to be brave but actually singular. I can find no other movie, except for maybe North Dallas Forty (the football movie with Nick Nolte and Mac Davis) and Oliver Stone's Any Given Sunday, that has such a low opinion of its subject. But Rollerball goes way further than those movies do in illustration (mainly because the genre to which it belongs allows such hyperbole). Here we have a populace that erupts into chaos with each metal-knuckled punch, hairy motorcycle wipe-out, and pointless goal (the steely 10-pound ball makes an aggressive CLANG every time a point is scored). And the film's notion of corporations taking over in the sporting world has become all too prescient. We all know who wins most of the time these days: it's the team with the most money in its coffers.

As a person who has always been at odds with the blind love of sports to which most seem to cling, I find Rollerball's anti-sports-violence stance not only to be brave but actually singular. I can find no other movie, except for maybe North Dallas Forty (the football movie with Nick Nolte and Mac Davis) and Oliver Stone's Any Given Sunday, that has such a low opinion of its subject. But Rollerball goes way further than those movies do in illustration (mainly because the genre to which it belongs allows such hyperbole). Here we have a populace that erupts into chaos with each metal-knuckled punch, hairy motorcycle wipe-out, and pointless goal (the steely 10-pound ball makes an aggressive CLANG every time a point is scored). And the film's notion of corporations taking over in the sporting world has become all too prescient. We all know who wins most of the time these days: it's the team with the most money in its coffers.  That said, there are some problems with Rollerball. For all its sports naysaying, it sure makes the game look great. The Rollerball sequences are some of the most exciting cinematic sports moments you're likely to ever see (Jewison, to his credit, does take the trouble to make us wince occasionally at the on-screen blitzkrieg). James Caan was a former college football star at Michigan State and--get this--a one-time regular on the rodeo circuit with the nickname "The Jewish Cowboy." This athleticism shows up in his committed physicality as Jonathan E. He doesn't just leave it to the stuntmen to do all this stuff; he and his "teammates" are actually skating around in the thick of it. However, how are we really supposed to eventually hate the game along with Jonathan when we're always looking forward to the next on-screen match-up? The film really wants to have it both ways, and it's a problem (though this is cleared up at the climax).

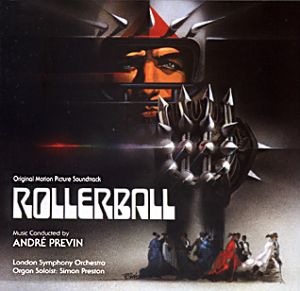

That said, there are some problems with Rollerball. For all its sports naysaying, it sure makes the game look great. The Rollerball sequences are some of the most exciting cinematic sports moments you're likely to ever see (Jewison, to his credit, does take the trouble to make us wince occasionally at the on-screen blitzkrieg). James Caan was a former college football star at Michigan State and--get this--a one-time regular on the rodeo circuit with the nickname "The Jewish Cowboy." This athleticism shows up in his committed physicality as Jonathan E. He doesn't just leave it to the stuntmen to do all this stuff; he and his "teammates" are actually skating around in the thick of it. However, how are we really supposed to eventually hate the game along with Jonathan when we're always looking forward to the next on-screen match-up? The film really wants to have it both ways, and it's a problem (though this is cleared up at the climax).  Also, though I adore way-off 1970s visions of the future, sometimes things go a little overboard here, particularly in a party sequence that pops up in the film's middle. The John Box production design, filled with billowy whites and harsh chromes, is a little embarrassing, and the Julie Harris costume design is the inevitable combo of "futuristic" spandex and gowny '70s awards show regalia. I like it, against my better angels, but others perhaps won't--though the design of the team uniforms is sharp. Neither will some enjoy Andre Previn's annoying futuremusik--electronic squeaks and squiggles done to a disco beat. (However, any

Also, though I adore way-off 1970s visions of the future, sometimes things go a little overboard here, particularly in a party sequence that pops up in the film's middle. The John Box production design, filled with billowy whites and harsh chromes, is a little embarrassing, and the Julie Harris costume design is the inevitable combo of "futuristic" spandex and gowny '70s awards show regalia. I like it, against my better angels, but others perhaps won't--though the design of the team uniforms is sharp. Neither will some enjoy Andre Previn's annoying futuremusik--electronic squeaks and squiggles done to a disco beat. (However, any  movie that begins--as this one strongly does--with an organ rendition of Bach's Toccata and Fugue in D Minor cannot be all bad!) I do love that the partygoers adjourn to nature to blow up trees with a powerful, fireball-spewing gun (I'm sure if one of those were on the market today, they'd be elms bursting into flames all over the place). And there's the occasional dull moment, usually involving Maud Adams as Jonathan's opportunistic lover. But then, to make up for that, there's Houseman (always good), a fine one-scene cameo with Ralph Richardson as a brainy librarian, and an energetic Moses Gunn as Jonathan's coach. So, with all of this, Rollerball is right on the edge of being a sinful pleasure for me. But a pleasure it remains...even if I do have to sometimes remind people it's not the one from 2002.

movie that begins--as this one strongly does--with an organ rendition of Bach's Toccata and Fugue in D Minor cannot be all bad!) I do love that the partygoers adjourn to nature to blow up trees with a powerful, fireball-spewing gun (I'm sure if one of those were on the market today, they'd be elms bursting into flames all over the place). And there's the occasional dull moment, usually involving Maud Adams as Jonathan's opportunistic lover. But then, to make up for that, there's Houseman (always good), a fine one-scene cameo with Ralph Richardson as a brainy librarian, and an energetic Moses Gunn as Jonathan's coach. So, with all of this, Rollerball is right on the edge of being a sinful pleasure for me. But a pleasure it remains...even if I do have to sometimes remind people it's not the one from 2002.

1 comment:

I don't think the film is trying to have it both ways. I think that Jewison wants the viewer to like the Rollerball matches in order for the viewer to understand how easily one can get caught up in the gladatorial spirit.

Then, once one is at his most involved in the match, he pulls some horrific act that implicates the viewer in the evils perpetrated by the corporations. The viewer then understands the sick feeling Jewison is trying to evoke.

Great essay. I'm nominating it for LAMB Chops, but this week was tough with your equally good essays on Pelham and Logan's Run.

Post a Comment