Studio One was an original series of stand-alone dramas that appeared on CBS for a full decade--1948 to 1958. In that time, the show gave the airwaves over to artists that would forever change the movie industry, while leaving TV and Broadway in the dust, standing lonely as mere training grounds for the movies (thus setting each up to be moviedom's minion, a stance which is now finally fading). Among Studio One's veterans: Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson, Charlton Heston, Jack Lemmon, James Dean, Eva Marie Saint, Joanne Woodward, Grace Kelly, Jason Robards, Jack Palance, Dennis Hopper, Peter Falk, Anne Bancroft, and directors Sidney Lumet (Network, Dog Day Afternoon, The Verdict), Robert Mulligan (To Kill a Mockingbird, The Other, Fear Strikes Out), Ralph Nelson (Lilies of the Field, Father Goose, Charly), and Franklin J. Schaffner (Patton, Planet of the Apes, Papillon). Obviously, Studio One was a juggernaut of quality.

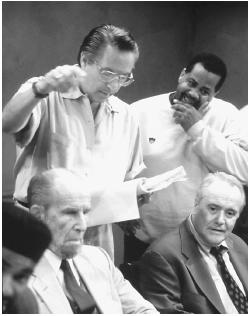

Studio One was an original series of stand-alone dramas that appeared on CBS for a full decade--1948 to 1958. In that time, the show gave the airwaves over to artists that would forever change the movie industry, while leaving TV and Broadway in the dust, standing lonely as mere training grounds for the movies (thus setting each up to be moviedom's minion, a stance which is now finally fading). Among Studio One's veterans: Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson, Charlton Heston, Jack Lemmon, James Dean, Eva Marie Saint, Joanne Woodward, Grace Kelly, Jason Robards, Jack Palance, Dennis Hopper, Peter Falk, Anne Bancroft, and directors Sidney Lumet (Network, Dog Day Afternoon, The Verdict), Robert Mulligan (To Kill a Mockingbird, The Other, Fear Strikes Out), Ralph Nelson (Lilies of the Field, Father Goose, Charly), and Franklin J. Schaffner (Patton, Planet of the Apes, Papillon). Obviously, Studio One was a juggernaut of quality. Writer Reginald Rose (pictured right) originally penned Twelve Angry Men in 1954 as just another episode in the series (a long-lost 16mm kinescope of which has recently been rediscovered). It took a few years, but when star Henry Fonda read Rose's teleplay almost two years later, something clicked. Fonda knew that Marty, another teleplay-turned-movie, had just nabbed the Oscar for Best Picture in 1955 (stealing the award away from another longtime Fonda project Mister Roberts). The critical success of Daniel Mann's film about a lovelorn butcher (Ernest Borgnine) was a clear signal that the movies were learning deeply from TV--to wit: small stories about small people could gain much strength on the big movie screen. And Fonda felt that Twelve Angry Men could be another step in proving this thesis.

So Fonda--as producer--wisely recruited Studio One's Sidney Lumet, a longtime television and stage presence, and trustingly gave him his first big-screen assignment. I now wonder if Henry Fonda felt like he'd just signed Babe Ruth away from his farm team, because the movie Lumet delivered has a solid place in the pantheon of cinema's most astonishing directorial debuts. Obviously a classic, Twelve Angry Men, though, is more than that; it's a film that's utterly entered into our consciousness. I would venture that every American who's ever been on a jury (if they've seen Lumet's film) understandably wonders if they're gonna end up as a hero and/or pariah like Henry Fonda is in the picture.

In it, the stalwart Fonda stars as Juror #8, the only one out of twelve who stubbornly believes in the possible innocence of the accused murderer on which this jury is struggling to pass judgment. Juror #8 (Rose cleverly has all the jurors remain anonymous during deliberation) and his steadfast leanings towards an innocent verdict unleashes a tremor of rotting emotions and hidden motivations amongst the other eleven guys cooped up in that sweltering summer jury room. The harried jurors, in numbered order, are:

In it, the stalwart Fonda stars as Juror #8, the only one out of twelve who stubbornly believes in the possible innocence of the accused murderer on which this jury is struggling to pass judgment. Juror #8 (Rose cleverly has all the jurors remain anonymous during deliberation) and his steadfast leanings towards an innocent verdict unleashes a tremor of rotting emotions and hidden motivations amongst the other eleven guys cooped up in that sweltering summer jury room. The harried jurors, in numbered order, are: Juror #1--level-headed Foreman Martin Balsam

Juror #2--mousy but tenacious John Fiedler

Juror #3--I'm-gonna-punch-yer-lights-out dad Lee J. Cobb

Juror #4--snooty rich guy E.G. Marshall

Juror #5--working guy Jack Klugman

Juror #6--working guy Edward Binns

Juror #7--sports fan Jack Warden

Juror #8--the dutiful Henry Fonda

Juror #9--old man Joseph Sweeney

Juror #10--total bigot Ed Begley

Juror #11--immigrant working guy George Voskovek

Juror #12--hip daddy-o adman Robert Webber

In 1981, when I first saw Twelve Angry Men on WOR-TV out of New York, I was 14 years old. As I first watched these guys heatedly deliberate over the fate of this possible innocent, my heart pounded wildly--it was as if it were my own life hanging in the balance. I'll never forget this feeling. I think this is exactly the way in which all viewers should see Twelve Angry Men. No movie ever has attempted to do what this movie does: here we are, in a democratic society, and we ourselves are entrusted with the guilt or innocence of a person in the dock. Therefore, WE have to live with the freedom or death of the person in question. Nothing in American cinema so effectively informs us of our civic responsibility as vividly as does Lumet's film. Instantly, even in 1957, this movie perfectly delineates the job each American must face--whether it be a shoplifting or a murder charge--once they are called upon to serve on a jury.

As a movie that takes place in one confined space--much like Louis Malle's My Dinner With Andre, Alfred Hitchcock's Lifeboat, Radha Bharadwaj's Closetland, or Giuseppe Tornatore's brilliant

A Pure Formality (with Roman Polanski and Gerard Depardieu as leads)--Twelve Angry Men always impresses us with its cinematic prowness. In particular, I'm reminded of the key scene where only raised hands are pictured casting votes, with a non-raised hand bespeaking a surprise turning of the tide for the tide for the meek young Latino man at bay. Limited in space in which to move around, Lumet's camerawork is nevertheless always fascinating; the man uses close-ups, choreography, light, long takes, shock cuts, and almost every other trick available to keep the film from being awkward, stiff or stagy. It's a real directorial achievement.

A Pure Formality (with Roman Polanski and Gerard Depardieu as leads)--Twelve Angry Men always impresses us with its cinematic prowness. In particular, I'm reminded of the key scene where only raised hands are pictured casting votes, with a non-raised hand bespeaking a surprise turning of the tide for the tide for the meek young Latino man at bay. Limited in space in which to move around, Lumet's camerawork is nevertheless always fascinating; the man uses close-ups, choreography, light, long takes, shock cuts, and almost every other trick available to keep the film from being awkward, stiff or stagy. It's a real directorial achievement.  Every actor in Twelve Angry Men gets his own moment: snobby E.G. Marshall has to adjust his glasses when backed into an unknowing corner; John Fiedler gets to stand up for himself when he realizes that everyone sees him as a creampuff; Lee J. Cobb had a heartbreaking, photo-tearing moment where he realizes that his prejudices stem from the contentious relationship he has with his own son; Jack Warden finally realizes he's been a damn fool for caring about a missed sporting event more than a man's life; Martin Balsam is the one who recognizes Fonda's exacting notions of the truth; Joseph Sweeney gets to realize that Fonda is right about a witnesses' possibly faulty eyesight; and, most notably, Ed Begley (Juror #10) finally sees that he's long been in the wrong blasting forth his hatred for minorities; he ultimately finds himself talking to the backs of everyone in the room in one of the cinema's greatest monologues:

Every actor in Twelve Angry Men gets his own moment: snobby E.G. Marshall has to adjust his glasses when backed into an unknowing corner; John Fiedler gets to stand up for himself when he realizes that everyone sees him as a creampuff; Lee J. Cobb had a heartbreaking, photo-tearing moment where he realizes that his prejudices stem from the contentious relationship he has with his own son; Jack Warden finally realizes he's been a damn fool for caring about a missed sporting event more than a man's life; Martin Balsam is the one who recognizes Fonda's exacting notions of the truth; Joseph Sweeney gets to realize that Fonda is right about a witnesses' possibly faulty eyesight; and, most notably, Ed Begley (Juror #10) finally sees that he's long been in the wrong blasting forth his hatred for minorities; he ultimately finds himself talking to the backs of everyone in the room in one of the cinema's greatest monologues: JUROR 10: I don't understand you people! I mean all these picky little points you keep bringing up. They don't mean nothing. You saw this kid just like I did. You're not gonna tell me you believe that phony story about losing the knife, and that business about being at the movies. Look, you know how these people lie! It's born in them! I mean what the heck? I don't have to tell you. They don't know what the truth is! And lemme tell you, they don't need any real big reason to kill someone, either! No sir! [#5 gets up from his seat] They get drunk... oh, they're real big drinkers, all of 'em - you know that - and bang: someone's lyin' in the gutter. Oh, nobody's blaming them for it. That's the way they are! By nature! You know what I mean? VIOLENT! [#9 rises and crosses to the window] Where're you going? Human life don't mean as much to

them as it does to us! [#11 gets up and walks to the other window]. Look, they're lushing it up and fighting all the time and if somebody gets killed, so somebody gets killed! They don't care! Oh, sure, there are some good things about 'em, too. Look, I'm the first one to say that. [#8 gets up and walks to the nearest wall] I've known a couple who were OK, but that's the exception, y'know what I mean?

them as it does to us! [#11 gets up and walks to the other window]. Look, they're lushing it up and fighting all the time and if somebody gets killed, so somebody gets killed! They don't care! Oh, sure, there are some good things about 'em, too. Look, I'm the first one to say that. [#8 gets up and walks to the nearest wall] I've known a couple who were OK, but that's the exception, y'know what I mean?[#2 and #6 get up from the table. Everyone's back is to #10] Most of 'em, it's like they have no feelings! They can do anything! What's goin' on here? I'm trying to tell you... you're makin' a big mistake, you people! This kid is a liar! I know it. I know all about them! Listen to me! They're no good! There's not a one of 'em who is any good! I mean, what's happening in here? I'm speaking my piece, and you... [the Foreman gets up and walks away. So does #12] Listen to me. We're... This kid on trial here... his type, well, don't you know about them? There's a--there's a danger here. These people are dangerous. They're wild. Listen to me. Listen... [and then, finally, after all this, #10 realizes who he really is, and sits down dejectedly].

In all of American cinema, there has been NOT ONE film that so clearly illustrates what it truly means to be an American as does Twelve Angry Men. Our jury system, for better or worse, is what makes Americans the fair-minded people they ultimately are. Lumet's film is a perfect illustration of such. In every way, it is an unassailable United States document.

PS: in the original version, played on TV in 1954, we had:

Norman Fell -- The Foreman

John Beal -- Juror #2

Franchot Tone -- Juror #3 (the Lee J. Cobb role)

Walter Abel -- Juror #4

Lee Philips -- Juror #5

Bart Burns -- Juror #6

Paul Hartman -- Juror #7

Robert Cummings -- Juror #8 (the Henry Fonda role)

Joseph Sweeney -- Juror #9 (he repeated his role in the movie)

Edward Arnold -- Juror #10

George Voskovec -- Juror #11 (he, too, repeated his role in the movie)

Larkin Ford (as Will West III) -- Juror #12

In William Friedkin's incredibly well-cast 1997 TV remake, we had:

In William Friedkin's incredibly well-cast 1997 TV remake, we had:Courtney B. Vance – the Foreman

Ossie Davis – Juror #2

George C. Scott – Juror #3 (the Lee J. Cobb role)

Armin Mueller-Stahl – Juror #4

Dorian Harewood – Juror #5

James Gandolfini – Juror #6

Tony Danza – Juror #7

Jack Lemmon – Juror #8 (the Henry Fonda role)

Hume Cronyn – Juror #9

Mykelti Williamson – Juror #10

Edward James Olmos – Juror #11

William Petersen – Juror #12

And, from here, Reginald Rose's Twelve Angry Men lives forever on stage and screen. Surely few American scripts deserve immortality more.

1 comment:

Hey dean---I haven't finished this article because I am unsure if you have any spoilers. I am going to be checking this film out soon and will come back and fully read it as soon as I finish it.

Post a Comment