Even before the credits roll, we hear a thin, girlish voice (meant to

recall the young tones of our female ingenue Pamela Franklin, here

playing Flora, though it could also be the voice of the deceased

governess Miss Jessel). Words are put to a vaguely secluded theme that

soon becomes the movie’s niggling, incessant refrain. Written by

composer George Auric and lyricist Paul Dehn, it’s a suitably

ancient-sounding tune called “O Willow Waly,” and it reeks of a

particularly lonely menace as we sit in the dark, waiting for a movie to

begin like we’ve never waited for a movie to begin before or since. And the 20th Century Fox logo happens in silence:

Even before the credits roll, we hear a thin, girlish voice (meant to

recall the young tones of our female ingenue Pamela Franklin, here

playing Flora, though it could also be the voice of the deceased

governess Miss Jessel). Words are put to a vaguely secluded theme that

soon becomes the movie’s niggling, incessant refrain. Written by

composer George Auric and lyricist Paul Dehn, it’s a suitably

ancient-sounding tune called “O Willow Waly,” and it reeks of a

particularly lonely menace as we sit in the dark, waiting for a movie to

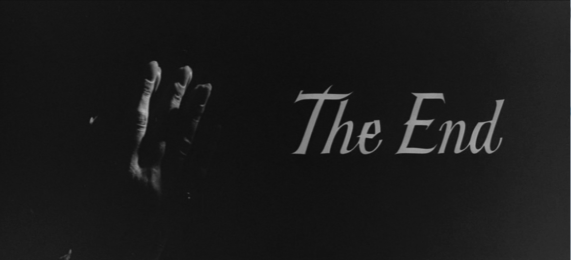

begin like we’ve never waited for a movie to begin before or since. And the 20th Century Fox logo happens in silence:Over the credits, we get a quick glimpse of what we will later learn is the movie’s climax–a clasp of Kerr’s praying hands, over which she breathlessly trembles and sweats, almost in erotic fervor. “I want to save the children, not destroy them,” she confesses in a whisper that flutters amongst twittering night birds. “More than anything, I love children. They need affection, love–someone who’ll belong to them, and to whom they would belong.”

We then eavesdrop on a moderate prologue in which we’re introduced to Michael Redgrave’s coldly profligate uncle as he hires Kerr’s Miss Giddens to take charge of the young rascals foisted upon him (he echoes–or precursors–Miss Giddens’ sentiments about providing them “someone who’ll belong to them, and to whom they would belong”). But he’s upfront about it: he has no time for them, and he’s looking to pay her to love the children for him (tellingly, his first interview question is: “Do you have an imagination?” and we will find Miss Giddens indeed has a fruitful one, of which she’s later a victim). The sheltered daughter of a radically religious country parson, she strikes us as someone of ulterior motives, because as much as she professes to love children, she’s only too willing to let her prospective employer off the hook for leaving his niece and nephew in the lurch as he gallivants carefree, spreading his influence around London. (Of course, she wants the job, so who is she to object?) Giddens clearly develops a crush on this cad, and throughout the rest of the movie, she’s adamant to do his bidding, even if he never appears before her (or us) again. He’s wealthy, but not someone worthy of love, yet she’s been shuttered away for so long, and so past her prime (Kerr is at once too old for the role, and altogether the perfect age for it) that the soulless uncle seems like some kind of perverse hero to her. Maybe, we’re left to conclude, he resembles her own father, who clearly had no room for his own children “mentally or emotionally.”

After being regaled of previous governess's appalling fate (and of its secretive quality–she’s told to never to speak of it, ever), Miss Giddens arrives at the cloistered Bligh estate glorified and fully embraced by Franklin’s Flora, who’s positively giddy at having a new person in her orbit. As if her own name were a call to action, Flora responds most powerfully to the blooming countryside engulfing the mansion (often, the movie’s environment, with its croaking frogs and flittering butterflies, feels like it's pulling us headfirst into its dizzying effulgence). As Miss Giddens first wanders beside the landscape’s mirrored pond, she can hear a far off voice calling “Flora! Flora!” When she's finally faced with the young girl, Miss Giddens is confused–to whom did that distant voice belong? She knows that Miles, the nephew, is off at boarding school. However, her faith in the innocence of children quickly brushes such uncertainty aside. She is caught up with meeting the ebullient Flora (whom we first see as a rippling mirror image in the pond–itself mirroring a later disturbing apparition). She’s immediately introduced into Flora’s vivid inner world, which Miss Giddens first sees as being entirely playful. She’s somewhat shocked when Flora introduces her reptilian best friend Rupert (a hapless tortoise), but otherwise, this feels like easy going.

The lively script, largely written by Truman Capote who adapted William Archibald’s play (Archibald had little to do with the screenplay, though he gets co-writing credit) then introduces us to the only adult character who has even a slippery grasp on what has befallen the children in their isolation. Mrs. Grose (Meg Jenkins) is an affable though ultimately simple-minded presence who at once puts Miss Giddens at ease and then, gradually, sets her upon a course to madness. Prone to superstition and secrets (“Stuff and nonsense,” she repeatedly says), she’s an unreliable voice, and the closer we seem to come to the truth via her accounts, the further the truth seems to drift away. Also drifting away are the niceties that first greet Miss Giddens, who first steps into the house overwhelmed by its opulence, and is quickly taken aback when she reaches out to touch some white roses and finds their leaves shedding away in decay. The young girl’s charms and wandering curiosity are discussed, and then Miss Giddens gets startled anew: It wasn’t Mrs. Grose calling Flora’s name earlier. And Flora, then, seems to know of Miles’ impending return to the estate, even though nothing has been mentioned of it. “Promise you won’t go away,” Flora pleads, and Miss Giddens assures her “I expect to be here a very long time.” And then when she and Mrs. Grose talk about the uncle, and the now-dead governess Miss Jessel, Grose lets it slip: “He had the devil’s own eye.”

As we take our first of many eerie candlelit tours through the labyrinthine house (shot with uncommonly well-choreographed lighting and creative lens choices--this stuff was really executed with proper detail), the film continually ratchets up our unease in subtle ways. Flora continually takes joy in the darkest things, whether it be the notion of being in two places at once, or waking before she dies (she misspeaks in delivering her nightly prayers), or being a soul who walks around after expiring (“Isn’t that what happens to some people?”) or ignoring those screeching, predatory sounds of nature that disturb her governess (“We must pretend we don’t hear it…then we won’t imagine things,” Flora instructs). Continually, we find this world rather billowy and beautiful, and at the same time certainly threatening. And Pamela Franklin’s eyes pierce our soul with their odd combination of knowing and purity, particularly when we find her predictions of Miles’ return come true via a letter informing of his dismissal from school (for a reason that’s never fully spelled out). It’s an unsettling moment but, as with many in the film, we can’t quite put our finger on why it is so (though Franklin’s subsequent line “Oh, look–it’s a lovely spider…and it’s eating a butterfly” place the viewer firmly in ghoulish territory).

Miles is played by Martin Stephens, a young actor who’d reached an apex of creepiness in British cinema only the year before when he appeared as the agile and otherworldly leader of the transfixing, blonde-headed children commanding Wolf Rilla’s Village of the Damned. His showing here surpasses that role in many ways, though it also recalls it: as in Rilla’s film, his Miles is “miles” beyond his years, and seems to know more about the cruel universe than either the viewer or the adults in the film have any ken. Like Flora, he first appears as an adorably rambunctious child, full of vigor. His masculine energy instantly captivates his governess, and she gladly reverts back to her preferred role upon meeting him. But Miss Giddens is then quickly suspicious of his ability to dirty up innocence, and this is the feeling that defines their odd relationship throughout the film (Mrs. Grose cackles at the governess’ distrust: “Are you afraid he’ll corrupt you?”). This notion becomes ever more alarming when we see that Miles resembles his uncle so, with his cravat and pompadoured hair, that he strikes the viewer (wholly subliminally) as a bonafide Mini-Me. The can’t be good for Miss Giddens, we know right from the outset, when he boldly hands her some flowers as introduction (“Charm must run in the family,” she cheerfully says to Mrs. Grose).

As Clayton’s masterfully directed piece progresses, Miles’ peculiarity becomes more disconcerting, and its causes become clearer (though the film, in keeping with the times it was made, is unable to articulate any details beyond furtive suggestion). The Innocents was mildly appreciated upon its first release (it won Best Director from the National Board of Review, but otherwise was ignored by critical voices, unjustifiably so). But it’s recently re-entered the conversation when discussing the most deeply layered of horror films, and as such, it’s received a much vaunted 2014 release as part of the Criterion Collection, so we can fully soak up Francis’ complex lighting schemes and deep focus framing. The cinematographer’s work shines brilliantly, particularly during the stunning dream sequences–complicated, lap-dissolving mosaics that have rarely seen equal (this would be a tremendously satisfying movie to see on the big screen). Director Clayton, as well, seductively applies sound and music to his creation, with moments of chatter and then thudding silences that will freeze your soul. Without revealing too much (lest I spoil its surprises), the film reaches only one of its many peaks when the ominous Miles, after a vigorous game of hide-and-seek, colludes with Flora to put on a show for the governess and Mrs. Grose. By candlelight, with a chintzy crown atop his head, he recites a morbid love poem to the departed–one that feels utterly like something out of Edgar Allen Poe, but which was directly written for the film as a kind of counterpart to Flora’s song (this must be a creation of Truman Capote, a poet of the first order):

What shall I sing to my lord from my window?

What shall I sing, for my lord will not stay?

What shall I sing, for my lord will not listen?

Where shall I go when my lord is away?

Whom shall I love when the moon is arisen?

Gone is my lord, and the grave is his prison.

What shall I say when my lord comes a-calling?

What shall I say when he knocks on my door?

What shall I say when his feet enter softly

Leaving the marks of his grave on my floor?

Enter my lord!

Come from your prison!

Come from your grave, for the moon is arisen

Welcome, my lord…

What shall I sing, for my lord will not stay?

What shall I sing, for my lord will not listen?

Where shall I go when my lord is away?

Whom shall I love when the moon is arisen?

Gone is my lord, and the grave is his prison.

What shall I say when my lord comes a-calling?

What shall I say when he knocks on my door?

What shall I say when his feet enter softly

Leaving the marks of his grave on my floor?

Enter my lord!

Come from your prison!

Come from your grave, for the moon is arisen

Welcome, my lord…

This provokes only one of many alarmed jolts from Kerr’s jittery, unstable governess, who indeed may not be as crazy as she seems (this is the movie's perfect height). Her bedside conversations with Miles become increasingly anxious, and one such encounter leads to a totally wrong-feeling moment between the two–one that couldn’t be shot nowadays without a uproar from concerned parents. Amidst spectral walks through deserted hallways, dusty attics, bug-ridden gardens, and wind-blown bedrooms, Clayton elegantly builds tension, to the point you think you mightn’t be able to stand another minute. The swirling, chaotic climax is the final punch to the gut, a shocking coda to all the dread that’s come before.

As a work about children, this might be the chanciest cinema has to offer, particularly given the time in which it was produced. If it were filmed today, the story might be spelled out too baldly, if it could be filmed at all. As it is, you can feel Clayton and screenwriter Capote dancing so close to the edge that the waltz becomes ridiculously perilous. There are innumerable regal and scuzzy scares in The Innocents. What remains in our consciousness, after the fear is shaken away, is the demarcation of that line between chastity and depravity. That’s exactly what’s so alarming about this movie’s splendid, gorgeously horrifying ambivalence. In the end, it’s concerned with what scurrilous details children might cull from seen and unseen adult sexuality. What can be more disquieting, or less innocent, than that? Yet, I think kids can watch this film and understand it fully.

NOTE: this review originally appeared in 2015 as part of WONDERS IN THE DARK's genre overview called THE CINEMA OF CHILDHOOD. Check the whole lineup out here:

No comments:

Post a Comment