The very concept of the new horror anthology film V/H/S is intriguing enough: a group of thugs, out to sell their video finds to an internet site, have been tipped off that a local house has a tasty stash of VHS tapes to mine for their "business." After running roughshod over the place, the guys come across a long-dead body in a room filled with television monitors. Even though the corpse supposedly stinks, one guy is commanded--for some ridiculous reason--to stay in the room while the others search the place for the tapes. This is a good way to split up the group because, you know...this is what horror movies do. So, in the meantime, this guy whiles time away by popping in a few tapes to review, and here we get into the bloody meat of the movie:

Episode one, "Amateur Night," is directed by Atlanta's David Brucker, one of three at the helm of 2007's quasi-zombiefest The Signal, and he's lucky he gets the first spot here because, as we get into V/H/S, we realize most of its stories are strikingly similar, so this first outing begins at a point of freshness. A group of hard-partying guys hit some Atlanta nightspots (including the legendary Star Bar), with plans to pick up a couple of girls and whist them away to a hotel room where they can videotape each having sex with them. The footage here is supposedly being shot through a pair of spy glasses that one reluctant predator is wearing. You can predict that things won't turn out so well for them, but I'm trying mighty hard to avoid spoilers here. Let's just say that this extremely well-edited segment stands as one of V/H/S' most entertaining (if rarely scary) offerings. Performance-wise (as with most of the acting in the film), there's not much to be said. All throughout V/H/S, we only see white, mostly male twentysomethings, so all the actors tend to blend together as they hit two notes: annoying wise-ass and screaming freak-out. On the other hand, the actresses in the movie tend to stand out, and here, one of the film's wide-eyed female victims (Hanna Fierman) seems like obvious trouble from the start. It's a fun if thinly-written piece, with an extremely short but memorable series of culminating shots that very well may be V/H/S's most frightening images.

Mumblecore progenitor Joe Swanberg stars in the next segment (but does not direct--this is a Ti West production). Titled "Second Honeymoon," it stars Swanberg and Sophia Takal as a troubled couple out to re-spark their romance via a trip to the Grand Canyon. This is one of V/H/S' most fascinating segments precisely because its horror elements are introduced rather late in the game. For me, though, the push-me/pull-you sexual dynamics at play here are the segment's greatest asset. Swanberg and Takal are pretty much perfect, especially in one scene that has Swanberg humorously admit to a scantilly-clad Takal that, as the man with a video camera, he has "a great idea" (we know what THAT is). Takal's piercing reaction is a fun moment of stinging non-horror joy. This is the one segment that could be considered more of a noir piece than a member of the horror genre.

The third segment is the least effective. Directed by I Sell The Dead's Glenn McQuaid, "Tuesday the 17th" is nothing more than a variation on a kids-in-the-woods slasher movie, with its only truly inventive element being a killer who can only be seen through the camera's viewfinder. The well-worn video effects here are smart, but that's its only positive (the acting in this segment is, also, quite pedestrian, which at least gives the viewer some way to judge the acting in the rest of V/H/S).

Swanberg reappears as the director of the fourth and unquestionably best of the bunch. "The Sick Thing That Happened To Emily When She Was Young" is posited as a series of Skype-like conferences between a wide-eyed innocent (a superb Helen Rogers) and her far-away boyfriend (who appears, of course, only in a little box in the bottom right corner of the frame). She's in a house that she insists is haunted, and she appeals to her guy to accompany her in finding out if she is indeed right. Not only is this the most frightening of the stories, it's the most filmically inventive (one complaint: who would transfer a Skype conversation to VHS in this day and age?). Still, it's no surprise that this piece is as good as it is; while Swanberg's not really known for his horror output, he's still the most accomplished director here. Whatever complaints one might have with the unfairly-named mumblecore movement, his collaborations with Greta Gerwig Nights and Weekends and Hannah Takes The Stairs are nonetheless laudible films. This segment also proves to be a welcome break from the hyperactive shaky-cam antics in V/H/S (Warning: this is EXTREMELY shaky shaky-cam territory here, which would probably account for the misleading reports of viewers throwing up during screenings).

Finally, after an unfortunate intrusion by Adam Wingard's largely useless wraparound piece, we get "10/31/98," which feels like an urban myth set to film. Yet ANOTHER group of asshole guys go out in costume to a Halloween party and find themselves at exactly the wrong address. Blended into this overlong piece is a climax which features extended digital effects that look quite fetching blended in with all the low-fi stuff. Still, by the time the filmmaking collective Radio Silence contributes this tale, my patience with V/H/S had worn away. The movie, at nearly 2 hours, is easily 20 minutes too long. There are only so many cookie-cutter shitty dudes I can watch in one sitting, even if most of them meet violent ends. This gimmicky gross-out has some notable moments and scares, but don't believe the hype: cripplingly light in the screenplay department, V/H/S hasn't reinvented a genre that, I feel, offers returns that diminish with each title released. But what the hell does it matter what I say? Horror fans will nonetheless scarf up this outing, as well as every other average-to-below genre title that's thrown their way.

Friday, March 30, 2012

Thursday, March 29, 2012

More Self-Promotion, thanks to Rich Gedney

I've met a new friend named Rich Gedney. I did so through a completely world-famous artist named Lisa Falour, who spearheaded one of the premiere early 80s Lower East Side NYC punk zines--and therefore the progenitor of the modern blog--called BIKINI GIRL. Through my friendship with her, I've connected with Rich, who does a fabulous YouTube blog about travel called RICH VOYAGES. He's extremely smart with a camera, and even without that thing, he's resolved himself to convincing people to get out of their comfort zone and connect not only with their neighbors but with their worldwide friends. Anyway, he and I have forged a new friendship, and I have to thank him for constructing this interesting little mini-resume, which lets y'all know what I'm into. Again, thanks, Rich!

What do you think? Am I okay on camera? Okay, I get another shot...here's my first food review, with Rich himself as host, as we talk about Atlanta's tasty BBQ joint The Mustard Seed.

What do you think? Am I okay on camera? Okay, I get another shot...here's my first food review, with Rich himself as host, as we talk about Atlanta's tasty BBQ joint The Mustard Seed.

2012 Atlanta Film Festival review: SWEET OLD WORLD

David Zeiger's somewhat gritty Sweet Old World might not seem so sweet on its surface (even until the very end, which features a needless, not-so-sweet death), but it's an expertly performed character piece that plays fair with almost all of its characters. Zeiger's background is as a documentary filmmaker who's trained his camera mostly on high school students, having done The Band for the PBS series POV, Senior Year, and the Indie Spirit award-winning Sir! No Sir!, about the efforts of Vietnam vets to contest the war they themselves fought in. This is Zeiger's first foray into narrative filmmaking, and in a rare move on my part, I defer to the director's own synopsis of his movie, because sometime said synopsis (with some editing, by me) is just perfect enough:

Sweet Old World is inspired by my personal documentary film, The Band (PBS series P.O.V., 1998), in which I followed my son through his junior year in high school as we both struggled with the death of his brother seven years earlier. It tells the fictional story of a father (Brian, played by John Nielsen) and his teenage son (Ethan, played by newcomer Jacques Colimon), both of whose lives were shattered when the son's brother was killed in an accident seven years earlier. Each trapped in their own private grief and pain, their relationship has grown strained and cold over the years. But the return of the dead son's best friend (Eric Peter-Kaiser), who left town after the accident, causes Brian and Ethan's carefully constructed protective shells to shatter, bringing them both to the brink of disaster and the potential for a new life and relationship. Throughout, the story is driven by Ethan, whose seemingly uncharacteristic willingness to flirt with danger under the influence of his brother's friend forces his father to confront his own buried grief. The story unfolds amidst a typical year in the life of Calfornia's South Pasadena High School Marching Band as a hundred disparate teenagers--including Ethan--and their teachers start from scratch to mold a complex program of music and motion.

Zeiger's documentary roots show spectacularly through in Sweet Old World's finest moments, as it follows co-lead Jacques Colimon (a mindful young actor who's terrific in his debut) as he travels through his high-school-band world (the scenes with the band are completely exquisite). John Nielsen--who thankfully gets as much screen time as Coliman--is also moving and extremely believable as Colimon's troubled father. These days, it's unusual to see a movie about a kid that pays an equal amount of respect to his parents; the mother, who gets less screen time, is also well-played by Gwendolyn Oliver. The film's most vivid performance comes from a supporting player, Julia Rose, who's cast as one of Ethan's teachers, an astute and compassionate educator who strikes up a tentative romantic dalliance with Ethan's father.

One of the things I love most about looking at ultra-indie films is trying to figure out who in the cast is going on to great things; with Sweet Old World, I had trouble deciding between the wide-eyed newcomer Colimon, the David Straithain-like weathered dad Nielsen (who has many excellent moments), and the harried mother Oliver. But (and this isn't a contest here) I had to internally side with Julia Rose, who had relatively little screen time but who totally convinced me in regard to her character. Everyone in Sweet Old World is worth giving more than a second look to, but Rose is absolutely on the mark in every one of her very difficult sequences. Here, though, I must return also to Colimon, who strike the proper balance between being innately intelligent and resolutely cool. His performance does what the screenplay can't do.

My one complaint with Sweet Old World is one that can be leveled against many festival-level indie features: It gets too bogged down in plot, and some of the screenplay machinations register as a no-go, mainly because they're based on what other movies do. For instance, when drug dealers are introduced into a story like this, you know where it's going. Unfortunately, that means that Eric Peter-Kaiser's long-haired wild thing--while personable enough--is cast down as the story's thankless villain. Though he tries mightily, Zeiger doesn't do enough to make this character completely sympathetic and as a result, we can see where the movie is heading plot-wise. As well, the idea of the photographer father's ham-handed retreat into his own past, as he secretively takes photos of his estranged son, seems a bit tired.

Even so, as a one-time film festival programmer, I can understand why Sweet Old World was included in the Atlanta Film Festival lineup. Even if a movie isn't perfect, sometime you want to root for its players (who might have only this one chance to show what they can do), and here we cheer for the film's passionate and little-seen cast and for its clearly devoted and experienced writer/director. I can't say I agree with every one of the latter's choices; in a post-screening Q&A, Zeiger admitted he's a fan of Belgium's Palme D'or-winning Dardenne brothers, but he obviously cannot replicate their disregard for the traditional screenplay (which really means that he hails from a market-driven America and, honestly, who out there can make films like the esteemed Dardennes?). That said, I nonetheless find myself totally on his side and, moreover, on the side of his well-chosen cast.

Sweet Old World is inspired by my personal documentary film, The Band (PBS series P.O.V., 1998), in which I followed my son through his junior year in high school as we both struggled with the death of his brother seven years earlier. It tells the fictional story of a father (Brian, played by John Nielsen) and his teenage son (Ethan, played by newcomer Jacques Colimon), both of whose lives were shattered when the son's brother was killed in an accident seven years earlier. Each trapped in their own private grief and pain, their relationship has grown strained and cold over the years. But the return of the dead son's best friend (Eric Peter-Kaiser), who left town after the accident, causes Brian and Ethan's carefully constructed protective shells to shatter, bringing them both to the brink of disaster and the potential for a new life and relationship. Throughout, the story is driven by Ethan, whose seemingly uncharacteristic willingness to flirt with danger under the influence of his brother's friend forces his father to confront his own buried grief. The story unfolds amidst a typical year in the life of Calfornia's South Pasadena High School Marching Band as a hundred disparate teenagers--including Ethan--and their teachers start from scratch to mold a complex program of music and motion.

Zeiger's documentary roots show spectacularly through in Sweet Old World's finest moments, as it follows co-lead Jacques Colimon (a mindful young actor who's terrific in his debut) as he travels through his high-school-band world (the scenes with the band are completely exquisite). John Nielsen--who thankfully gets as much screen time as Coliman--is also moving and extremely believable as Colimon's troubled father. These days, it's unusual to see a movie about a kid that pays an equal amount of respect to his parents; the mother, who gets less screen time, is also well-played by Gwendolyn Oliver. The film's most vivid performance comes from a supporting player, Julia Rose, who's cast as one of Ethan's teachers, an astute and compassionate educator who strikes up a tentative romantic dalliance with Ethan's father.

One of the things I love most about looking at ultra-indie films is trying to figure out who in the cast is going on to great things; with Sweet Old World, I had trouble deciding between the wide-eyed newcomer Colimon, the David Straithain-like weathered dad Nielsen (who has many excellent moments), and the harried mother Oliver. But (and this isn't a contest here) I had to internally side with Julia Rose, who had relatively little screen time but who totally convinced me in regard to her character. Everyone in Sweet Old World is worth giving more than a second look to, but Rose is absolutely on the mark in every one of her very difficult sequences. Here, though, I must return also to Colimon, who strike the proper balance between being innately intelligent and resolutely cool. His performance does what the screenplay can't do.

My one complaint with Sweet Old World is one that can be leveled against many festival-level indie features: It gets too bogged down in plot, and some of the screenplay machinations register as a no-go, mainly because they're based on what other movies do. For instance, when drug dealers are introduced into a story like this, you know where it's going. Unfortunately, that means that Eric Peter-Kaiser's long-haired wild thing--while personable enough--is cast down as the story's thankless villain. Though he tries mightily, Zeiger doesn't do enough to make this character completely sympathetic and as a result, we can see where the movie is heading plot-wise. As well, the idea of the photographer father's ham-handed retreat into his own past, as he secretively takes photos of his estranged son, seems a bit tired.

Even so, as a one-time film festival programmer, I can understand why Sweet Old World was included in the Atlanta Film Festival lineup. Even if a movie isn't perfect, sometime you want to root for its players (who might have only this one chance to show what they can do), and here we cheer for the film's passionate and little-seen cast and for its clearly devoted and experienced writer/director. I can't say I agree with every one of the latter's choices; in a post-screening Q&A, Zeiger admitted he's a fan of Belgium's Palme D'or-winning Dardenne brothers, but he obviously cannot replicate their disregard for the traditional screenplay (which really means that he hails from a market-driven America and, honestly, who out there can make films like the esteemed Dardennes?). That said, I nonetheless find myself totally on his side and, moreover, on the side of his well-chosen cast.

Wednesday, March 28, 2012

2012 Atlanta Film Festival review: CLOUDBURST

Oscar-winning actresses Olympia Dukakis and Brenda Fricker are, not surprisingly, literally and figuratively the heroines of Thom Fitzgerald's good-hearted Cloudburst. They're the primary reason to see this very Canadian-flavored movie, which casts them as aging lesbians (who've been a couple for 30 years) as they escape their close-minded Maine community to travel to a Canuck territory where they can legally get married. The political ramifications of such a story are obvious but, to its credit, Cloudburst doesn't spend much time preaching about the rights issues here. It hopes you understand.

Instead, when this honeyed little movie focuses in on character only, it's delicious--as long as the characters we're seeing are Dukakis' stern and butch Stella, and Fricker's sweet and infirmed Dot. They make a beautiful team and, though the scenes that involve ONLY these two are few, these moments are spectacular--yet the movie could have used more of them. You can really feel these two women leaping into these roles head first. Dukakis, especially, posits a transformative performance in which NONE of her previous film work can be seen; this is new ground for her. Dressed in well-worn western wear, with a ridiculously funny foul mouth, a short-cropped and parted grey head of hair, and a wincing scowl that breaks into unimpeded laughter in all the best places, Dukakis is uniformly perfect in the film. If you're paying money or time to see this movie, you're paying for Olympia Dukakis.

Fricker, playing a blind woman whose health is failing (you can see what's coming here), is also quite fetching, though less is really demanded of her here. Yet, I have to say, I wish more of Cloudburst portrayed, only, the relationship between these chipper women. The finest scenes in the film have them both at the center: an amazing diner confrontation in which an unusually logical (and romantic, in its own way) marriage proposal is offered by Dukakis, and is accepted with hysterical conditions by Fricker; and the most touching scene in Fitzgerald's film--a seaside and rainswept profession of love between the two that culminates in the most eloquent movie kiss I've seen in a long, long time.

The problems with Cloudburst come with its supporting players, who are simply no match for the leads. Their roles aren't written all that well, and the actors cast just can't muster up. Chief among them is Ryan Doucette, a hunky young hitchhiker adopted by the couple while on the road. He plays a well-toned dancer who uses his good looks to get what he wants (which, admittedly, makes the situation he finds himself in with these committed lesbians sometimes touching and hilarious). But Doucette, as an actor, is good but just not notably AS good as the veterans he's cast against. He has a wonderful scene towards the end where he dances with clunky grace to a Tony Orlando and Dawn song (Dukakis helps here with her mirthful reaction). But the introduction of his character momentarily veers the focus of the movie towards him (there's even a stop at his family's home, which yields a wild scene of physical comedy involving wacky male nudity, but really doesn't transmit much beyond that). Cloudburst should have been about its two female leads almost only, but Fitzgerald obviously felt they needed to include more, which means that he lacked confidence in the story's true power (to be fair, maybe the tyranny of the movie marketplace made him alter his true ambitions).

There's a lot of choice dialogue in Cloudburst, mostly handed to Dukakis' character, in which she regales on about the tastiness of k.d. lang (whose songs generously appear here), the quality of the word "cunt," the proper way to refer to a "flock of lesbians," and offers possibly the greatest "fuck you" ever delivered by a lesbian to a straight guy. And Fitzgerald (with cinematographer Tom Harting) captures the Canadian countryside with much care and love, while wisely avoiding the trope of ramming an accompanying soundtrack into your ears (the music is there, but it's mixed with extreme wisdom). However, the film avoids greatness by pandering to plot via its less effective characters and, perhaps, its filmmakers' perceived audience needs. Yet nothing can erase the achievements of Olympia Dukakis and Brenda Fricker, both of whom obviously saw opportunities to stretch here. If you know that these stellar ladies are the stars, and even if you don't have an open mind, hell, you need to see this movie. It's not entirely perfect, but it likely will graze your sense of understanding if you're approaching it blind, and if you're with it from the outset, it'll probably rock your world.

Instead, when this honeyed little movie focuses in on character only, it's delicious--as long as the characters we're seeing are Dukakis' stern and butch Stella, and Fricker's sweet and infirmed Dot. They make a beautiful team and, though the scenes that involve ONLY these two are few, these moments are spectacular--yet the movie could have used more of them. You can really feel these two women leaping into these roles head first. Dukakis, especially, posits a transformative performance in which NONE of her previous film work can be seen; this is new ground for her. Dressed in well-worn western wear, with a ridiculously funny foul mouth, a short-cropped and parted grey head of hair, and a wincing scowl that breaks into unimpeded laughter in all the best places, Dukakis is uniformly perfect in the film. If you're paying money or time to see this movie, you're paying for Olympia Dukakis.

Fricker, playing a blind woman whose health is failing (you can see what's coming here), is also quite fetching, though less is really demanded of her here. Yet, I have to say, I wish more of Cloudburst portrayed, only, the relationship between these chipper women. The finest scenes in the film have them both at the center: an amazing diner confrontation in which an unusually logical (and romantic, in its own way) marriage proposal is offered by Dukakis, and is accepted with hysterical conditions by Fricker; and the most touching scene in Fitzgerald's film--a seaside and rainswept profession of love between the two that culminates in the most eloquent movie kiss I've seen in a long, long time.

The problems with Cloudburst come with its supporting players, who are simply no match for the leads. Their roles aren't written all that well, and the actors cast just can't muster up. Chief among them is Ryan Doucette, a hunky young hitchhiker adopted by the couple while on the road. He plays a well-toned dancer who uses his good looks to get what he wants (which, admittedly, makes the situation he finds himself in with these committed lesbians sometimes touching and hilarious). But Doucette, as an actor, is good but just not notably AS good as the veterans he's cast against. He has a wonderful scene towards the end where he dances with clunky grace to a Tony Orlando and Dawn song (Dukakis helps here with her mirthful reaction). But the introduction of his character momentarily veers the focus of the movie towards him (there's even a stop at his family's home, which yields a wild scene of physical comedy involving wacky male nudity, but really doesn't transmit much beyond that). Cloudburst should have been about its two female leads almost only, but Fitzgerald obviously felt they needed to include more, which means that he lacked confidence in the story's true power (to be fair, maybe the tyranny of the movie marketplace made him alter his true ambitions).

There's a lot of choice dialogue in Cloudburst, mostly handed to Dukakis' character, in which she regales on about the tastiness of k.d. lang (whose songs generously appear here), the quality of the word "cunt," the proper way to refer to a "flock of lesbians," and offers possibly the greatest "fuck you" ever delivered by a lesbian to a straight guy. And Fitzgerald (with cinematographer Tom Harting) captures the Canadian countryside with much care and love, while wisely avoiding the trope of ramming an accompanying soundtrack into your ears (the music is there, but it's mixed with extreme wisdom). However, the film avoids greatness by pandering to plot via its less effective characters and, perhaps, its filmmakers' perceived audience needs. Yet nothing can erase the achievements of Olympia Dukakis and Brenda Fricker, both of whom obviously saw opportunities to stretch here. If you know that these stellar ladies are the stars, and even if you don't have an open mind, hell, you need to see this movie. It's not entirely perfect, but it likely will graze your sense of understanding if you're approaching it blind, and if you're with it from the outset, it'll probably rock your world.

Sunday, March 25, 2012

2012 Atlanta Film Festival: Day 2

Ahh, here's where reality sets in...

After a satisfying opening night, the Atlanta Film Festival's faults are showing through in its second day. Most chief of those faults is the tendency (like many film festivals have) to put the needs of corporate sponsors, local filmmakers, and undemanding audiences ahead of a mission which, to my mind, should ONLY be about showing the best of the best to attending film fans. What I'm trying to say is: I had a hard time finding anything I loved at the fest on Saturday. Here are my reviews:

The oddly-titled feature documentary Flat Daddy deals with four families and how they've been affected by the absence of loved ones who are off fighting the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. The filmmakers follow mothers in North Dakota and New York City, a Minnesota grandmother taking care of the children of her deployed son and daughter-in-law, and a Nevada parent grieving over the loss of her son. The title, which is bizarre mainly because it's not germane to the film, refers to the lifesize cardboard-cutout photos that serve as family member stand-ins (which one of the mothers has made a business out of producing). Really, though, Flat Daddy is about nothing more than giving an uncritical 90-minute rah-rah to the troops and their families. And I guess that's all well and good, but never is an examining eye given to what these families think of these wars or the crippling, excessively repeated deployments that have stolen these soldiers away. To a frame, the film just falls into too-familiar territory, like bittersweetly cute scenes of the kids talking about daddies they've never really known, or shattering scenes of mothers crying over coffins. The film's heart is in the right place, but its brain (or at least its sense of curiosity) has checked out; there's nothing here you haven't seen on a hundred local news war-veteran-related profile pieces.

Everyone knows clowns aren't really funny, and Brazil's The Clown isn't likely to change any minds. Suffering from an overdose of Coen Brothers-inspired quirks that fail to charm, The Clown follows the morose leader of a travelling circus who, midway through the movie, reveals a wish for a blander life. The director/co-writer/star Selton Mello is blessed with expert art directors and costumers who help make the movie pop visually. And his casting director has an eye for idiosyncratic faces, this is true. But Mello stumbles in that he can't reproduce the sort of driving narrative that hallmarks the best Coen Brothers movies. Instead, The Clown is leaden with scenes of mirth that aren't all that funny (the clown scenes leave us particularly cold, even though audiences in the film are directed to react like they're seeing the very invention of comedy), scenes of sentiment that don't earn the tears they so crave, and a plot that reveals itself way after our patience with the film has worn down to a nub. Particularly annoying here is a plunk-plunky musical score and a odd directorial insistence on overusing the ultra-slow-zoom, a technique usually reserved for scenes with some import but here used in almost every shot (which can really give one a headache). On the up side, at least the cast is relatively easy-to-watch and the countryside is pretty.

The Drama Shorts program included the following:

Los Angeles 10101 - 3 AM is a very slight piece detailing a booty call between people who ultimately have nothing to say to each other. This is another example of a film that's too short to be complete; two scenes (one of which focused solely on a 2-min POV shot of a phone being used for texting) does not a movie make. That said, I did appreciate its uncomfortable and extended final shot.

Winter Frog, a slightly flawed film from France's Slony Sow, has the big-time benefit of having a seasoned star like Gerard Depardieu in its corner. The acting legend (who now is Marlon Brando-like in girth) shows finesse and attention to detail as he portrays a emotionally devastated recent widower who finds inspiration from a young Japanese wine enthusiast invited to the vineyard by his late wife. The film could use another pass at editing, but it's nicely shot, smartly written, and effectively sentimental without being cloying.

A Hard Day's Pay follows the reluctant reunion between a financially desperate man and the gruff grandfather he hasn't seen in 10 years. Will Davies is good as the hardnosed oldster, but the film feels like well-worn country-noir territory and never really surprises. It's a movie that's just sort of...blah.

The third film in a row to combine drinking with the use of shotguns, Father/Son is the ridiculous tale of a son bringing his girlfriend to meet his decadent father, who develops designs on the girl. This one has the laughing-at-it, not with-it, kind of funniness (but I assume the filmmakers want us to take this tripe seriously, since the movie is programmed in the Drama Shorts block). The worst kind of indie film, Father/Son loves pressing our "ewwww" buttons. But, really, nothing could be a bigger waste of time...

Even worse is 4:00 AM, an Atlanta film spearheaded by local theater troupe Push Push Theater. All I can say is: stick to the stage, guys. This incomprehensible nonsense, inspired by the mysterious and schizo "Toynbee Tiles," sets a Toynbee-worshipping cult member against a cliched late-night talk show host who tries to talk sense but instead ends up sounding just as scatter-brained (the script sounds like it was either written by a extreme stoner or lifted from Eric Bogosian's overrated Talk Radio, though the film's credits include the card "Words by David Mamet"). The fit-inducing frame-fucking here includes fleeting, illegally-used scenes from numerous movies including 2001, The Elephant Man, and Night of the Living Dead. Note to all filmmakers: try not to remind viewers of other BETTER movies they could be watching instead of the shitty one you've made.

Landon Zakheim's Another Bullet Dodged is a ruthless poison-penned piece that, thankfully, broke the festival's losing streak with me. A callous boyfriend is late to pick up a girl, who's going for in for the abortion of their baby, and we follow this emotionless, morally-suspect guy through what should be a traumatic event. This is a nearly perfect short drama--well-paced, controlled, with a concise thesis, terrific acting by its two leads, and a daring sense of frankness. Harsh and unforgiving, Another Bullet Dodged made the audience I was with uncomfortable as hell, probably because many of the hipster guys in attendance saw a lot of themselves in it. The applause that followed it (and usually followed all entries) was notably reluctant and guilty, which I found to be hilarious.

I wish I could just gloss over another Atlanta film, called Terminus, but I can't. It just had no business being in the festival. If you've seen John Hillcoat's version of Cormac McCarthy's The Road, you'll recognize everything this movie has to offer. I mean, why make a film if it's merely a direct lift of a few scenes from another movie (only this time it's a kid and his sister wandering the lonely post-apocalyptic road)? The fact that this was programmed is the worst sort of mutual masturbation practiced between the Atlanta Film Festival and local filmmakers and, even though each get to shoot their loads, they're not really doing each other (or audiences) any favors in the long run.

Ben Sharony's magnificent Last Words of the Holy Ghost was another welcome relief from the badness. Adapted from a short story by Michael Cashion, it breaks from the previous shorts by being visually bright and colorful (apparently, for most filmmakers, drama means murky darkness). The 20-minute film also feature the very best writing so far at the AFF, telling of a horny rural teenager who has his sights set on a particular sensuous beauty...but the girl won't date him because he hasn't been "saved" by Jesus. This movie get everything right: the dialogue and situations are fun and then turn infuriating, the acting is expert, the emotions are real (the sense of understanding that infuses the film's climax is brilliantly surprising), the editing is exact, and the direction dynamic. Decorated with some positively lyrical narration, the lovely Last Words of the Holy Ghost is currently my favorite narrative film of the festival.

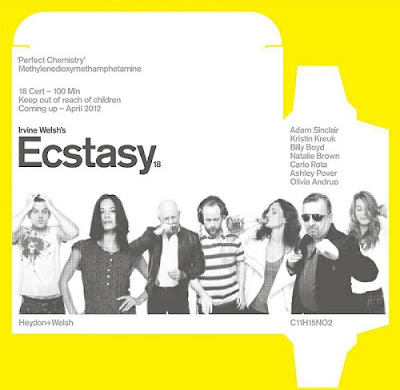

I ended the night by reluctantly sitting through Scottish director Rob Heydon's feature-length adaptation of Irvine Welsh's Ecstasy. If you can't tell from the poster pictured above, the movie owes almost everything to Danny Boyle's much-loved Trainspotting, also based on a Welsh novel. In fact, if you just replace heroin with ecstasy, and then take out most of Trainspotting's great acting, stunning visuals and soundtrack gems, you pretty much have this film. I mean, Ecstasy even features scenes where the main characters are introduced with name-emblazoned freeze frames. Heydon's film is all about such unoriginal pandering, though there IS a sex scene in it that's unlike any I've ever seen, mainly because the two lovers are listening to separate Ipods while they fuck. (Do people really DO that? That's fucking creepy--literally!) Still, this is a movie made for Trainspotting fans who want to see Trainspotting all over again, but...y'know...different. But, for a movie about partying hard, I found it quite dull, not well-observed (you never get a sense of how the drug ecstasy FEELS), preachy, and rather safe.

After a satisfying opening night, the Atlanta Film Festival's faults are showing through in its second day. Most chief of those faults is the tendency (like many film festivals have) to put the needs of corporate sponsors, local filmmakers, and undemanding audiences ahead of a mission which, to my mind, should ONLY be about showing the best of the best to attending film fans. What I'm trying to say is: I had a hard time finding anything I loved at the fest on Saturday. Here are my reviews:

The oddly-titled feature documentary Flat Daddy deals with four families and how they've been affected by the absence of loved ones who are off fighting the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. The filmmakers follow mothers in North Dakota and New York City, a Minnesota grandmother taking care of the children of her deployed son and daughter-in-law, and a Nevada parent grieving over the loss of her son. The title, which is bizarre mainly because it's not germane to the film, refers to the lifesize cardboard-cutout photos that serve as family member stand-ins (which one of the mothers has made a business out of producing). Really, though, Flat Daddy is about nothing more than giving an uncritical 90-minute rah-rah to the troops and their families. And I guess that's all well and good, but never is an examining eye given to what these families think of these wars or the crippling, excessively repeated deployments that have stolen these soldiers away. To a frame, the film just falls into too-familiar territory, like bittersweetly cute scenes of the kids talking about daddies they've never really known, or shattering scenes of mothers crying over coffins. The film's heart is in the right place, but its brain (or at least its sense of curiosity) has checked out; there's nothing here you haven't seen on a hundred local news war-veteran-related profile pieces.

Everyone knows clowns aren't really funny, and Brazil's The Clown isn't likely to change any minds. Suffering from an overdose of Coen Brothers-inspired quirks that fail to charm, The Clown follows the morose leader of a travelling circus who, midway through the movie, reveals a wish for a blander life. The director/co-writer/star Selton Mello is blessed with expert art directors and costumers who help make the movie pop visually. And his casting director has an eye for idiosyncratic faces, this is true. But Mello stumbles in that he can't reproduce the sort of driving narrative that hallmarks the best Coen Brothers movies. Instead, The Clown is leaden with scenes of mirth that aren't all that funny (the clown scenes leave us particularly cold, even though audiences in the film are directed to react like they're seeing the very invention of comedy), scenes of sentiment that don't earn the tears they so crave, and a plot that reveals itself way after our patience with the film has worn down to a nub. Particularly annoying here is a plunk-plunky musical score and a odd directorial insistence on overusing the ultra-slow-zoom, a technique usually reserved for scenes with some import but here used in almost every shot (which can really give one a headache). On the up side, at least the cast is relatively easy-to-watch and the countryside is pretty.

The Drama Shorts program included the following:

Los Angeles 10101 - 3 AM is a very slight piece detailing a booty call between people who ultimately have nothing to say to each other. This is another example of a film that's too short to be complete; two scenes (one of which focused solely on a 2-min POV shot of a phone being used for texting) does not a movie make. That said, I did appreciate its uncomfortable and extended final shot.

Winter Frog, a slightly flawed film from France's Slony Sow, has the big-time benefit of having a seasoned star like Gerard Depardieu in its corner. The acting legend (who now is Marlon Brando-like in girth) shows finesse and attention to detail as he portrays a emotionally devastated recent widower who finds inspiration from a young Japanese wine enthusiast invited to the vineyard by his late wife. The film could use another pass at editing, but it's nicely shot, smartly written, and effectively sentimental without being cloying.

A Hard Day's Pay follows the reluctant reunion between a financially desperate man and the gruff grandfather he hasn't seen in 10 years. Will Davies is good as the hardnosed oldster, but the film feels like well-worn country-noir territory and never really surprises. It's a movie that's just sort of...blah.

The third film in a row to combine drinking with the use of shotguns, Father/Son is the ridiculous tale of a son bringing his girlfriend to meet his decadent father, who develops designs on the girl. This one has the laughing-at-it, not with-it, kind of funniness (but I assume the filmmakers want us to take this tripe seriously, since the movie is programmed in the Drama Shorts block). The worst kind of indie film, Father/Son loves pressing our "ewwww" buttons. But, really, nothing could be a bigger waste of time...

Even worse is 4:00 AM, an Atlanta film spearheaded by local theater troupe Push Push Theater. All I can say is: stick to the stage, guys. This incomprehensible nonsense, inspired by the mysterious and schizo "Toynbee Tiles," sets a Toynbee-worshipping cult member against a cliched late-night talk show host who tries to talk sense but instead ends up sounding just as scatter-brained (the script sounds like it was either written by a extreme stoner or lifted from Eric Bogosian's overrated Talk Radio, though the film's credits include the card "Words by David Mamet"). The fit-inducing frame-fucking here includes fleeting, illegally-used scenes from numerous movies including 2001, The Elephant Man, and Night of the Living Dead. Note to all filmmakers: try not to remind viewers of other BETTER movies they could be watching instead of the shitty one you've made.

Landon Zakheim's Another Bullet Dodged is a ruthless poison-penned piece that, thankfully, broke the festival's losing streak with me. A callous boyfriend is late to pick up a girl, who's going for in for the abortion of their baby, and we follow this emotionless, morally-suspect guy through what should be a traumatic event. This is a nearly perfect short drama--well-paced, controlled, with a concise thesis, terrific acting by its two leads, and a daring sense of frankness. Harsh and unforgiving, Another Bullet Dodged made the audience I was with uncomfortable as hell, probably because many of the hipster guys in attendance saw a lot of themselves in it. The applause that followed it (and usually followed all entries) was notably reluctant and guilty, which I found to be hilarious.

I wish I could just gloss over another Atlanta film, called Terminus, but I can't. It just had no business being in the festival. If you've seen John Hillcoat's version of Cormac McCarthy's The Road, you'll recognize everything this movie has to offer. I mean, why make a film if it's merely a direct lift of a few scenes from another movie (only this time it's a kid and his sister wandering the lonely post-apocalyptic road)? The fact that this was programmed is the worst sort of mutual masturbation practiced between the Atlanta Film Festival and local filmmakers and, even though each get to shoot their loads, they're not really doing each other (or audiences) any favors in the long run.

Ben Sharony's magnificent Last Words of the Holy Ghost was another welcome relief from the badness. Adapted from a short story by Michael Cashion, it breaks from the previous shorts by being visually bright and colorful (apparently, for most filmmakers, drama means murky darkness). The 20-minute film also feature the very best writing so far at the AFF, telling of a horny rural teenager who has his sights set on a particular sensuous beauty...but the girl won't date him because he hasn't been "saved" by Jesus. This movie get everything right: the dialogue and situations are fun and then turn infuriating, the acting is expert, the emotions are real (the sense of understanding that infuses the film's climax is brilliantly surprising), the editing is exact, and the direction dynamic. Decorated with some positively lyrical narration, the lovely Last Words of the Holy Ghost is currently my favorite narrative film of the festival.

I ended the night by reluctantly sitting through Scottish director Rob Heydon's feature-length adaptation of Irvine Welsh's Ecstasy. If you can't tell from the poster pictured above, the movie owes almost everything to Danny Boyle's much-loved Trainspotting, also based on a Welsh novel. In fact, if you just replace heroin with ecstasy, and then take out most of Trainspotting's great acting, stunning visuals and soundtrack gems, you pretty much have this film. I mean, Ecstasy even features scenes where the main characters are introduced with name-emblazoned freeze frames. Heydon's film is all about such unoriginal pandering, though there IS a sex scene in it that's unlike any I've ever seen, mainly because the two lovers are listening to separate Ipods while they fuck. (Do people really DO that? That's fucking creepy--literally!) Still, this is a movie made for Trainspotting fans who want to see Trainspotting all over again, but...y'know...different. But, for a movie about partying hard, I found it quite dull, not well-observed (you never get a sense of how the drug ecstasy FEELS), preachy, and rather safe.

Saturday, March 24, 2012

2012 Atlanta Film Festival: Opening Night

Many die-hard film fans might not guess this, but the Atlanta Film Festival is one of the oldest events of its kind in America. Wikipedia says it was started in 1976, but I seem to remember that it's even older than that. I remember reading once that it was started in 1972, with famed Georgia-stamped picture Deliverance as its opening night offering (which would make the fest 40 this year). But I have to go by what it's being labelled as now, which would put its birth date smack dab in the nation's Bicentennial. The only U.S. fests that're older and still running are the San Francisco Film Festival (b. 1957), the New York Film Festival (b. 1963, and to my mind, the greatest of all American film fests), and Colorado's Telluride (b. 1974). It never ceases to amaze me that I live in a town that is a pioneer of the now-ubiquitous film festival circuit.

I have, of course, attained tickets to the Atlanta Film Festival in the past; most memorably, I attended 2003's opening night film, Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini's adaptation of Harvey Pekar's genius-infused comic American Splendor, which went on to win an award at Cannes and an Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay. I was so excited that night because I had been a longtime fan of Pekar's, and had interviewed him way back in 1987. Being good friends with that year's Programming Director Brian Newman (whom I last saw working for Robert De Niro's TriBeCa Film Festival when I attended that in 2008), I took it upon myself to hand out to some lucky attendees ONLY 100 copies of my original 4-page 1987 interview, which was printed for Georgia State University's newspaper The Signal back when they had a separate magazine section (which I edited for four years) called Tuesday Magazine. (By the way, that's where I got my start as a film reviewer in 1984, at age 17; my first piece was on Alex Cox's Repo Man and can be read here.)

The closest I've ever come to working for the Atlanta Film Festival was in 2006, when my friend Jake Jacobson (officially the only person I've ever known personally who knows more about movies than I do) was the Programming Director. Knowing that I had been a festival programmer myself (for the long-gone Dahlonega International Film Festival, b. 2000 - d. 2004), he enlisted me as a screener. This means I took home almost 300 entries for the festival, and I again took it upon myself to write mini-reviews for each of the films I was charged with reviewing. Jake and his Assistant Programmer Mike Malloy (who has an exciting film in this year's fest called Eurocrime! The Italian Cop and Gangster Films That Ruled the 70s) even had me in the room with them as they were finding slots for each of the films accepted that year, and I like to think I had a major influence there as an unpaid volunteer expert. Our opening film that year was Morgan Nichol's neo-noir film The Little Death--a controversial choice, as it had no stars in it and no pre-advance buzz. But we all decided it was the best of the fest, and didn't back down from our choice. I still think that's a brilliant movie, and am sorry it's so hard to see now.

But this year is the first in which I'm attending the festival as press, thanks primarily to my involvement with Jamey Duvall's estimable Movie Geeks United podcast and, secondarily, as the the writer of this here blog (which is more popular than I know, I suppose). In fact, this is only the fifth annual film fest I've been at as a media guy (I've been to three editions of the New York Film Festival this decade, and 2008's TriBeCa Film Festival, and you can see my reports on each here on FILMICABILITY).

Now that I'm back in Atlanta, after a long sojourn in the Big Apple, I am proud to say that I've been accepted as press here at this year's Atlanta Film Festival, so I'm going to give it my all and report on as many films as I can here. I might not give them all the attention I gave to Shame, The Artist, Once Upon A Time in Anatolia, Martha Marcy Mae Marlene, Melancholia, Footnote, and a few others that I saw at 2011's New York Film Festival, but I certainly will give each film I see an honest (and I mean HONEST) review here over the coming week. I owe this to the city I call home, and to the filmmakers who're contributing to it.

Here are the perhaps not-entirely accurate numbers this year...

45 narrative features

41 documentary features

52 narrative shorts

17 documentary shorts

30 animated shorts

14 experimental shorts

20 music videos

1 retrospective (Stanley Donen's Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, with Jane Russell in attendence)

...culminating in a grand total of 220 filmed works, exhibited over the course of nine days (from March 23rd to April 1st--you can see the entire lineup here at http://www.atlantafilmfestival.com) at nine venues, most of which are centrally located around Landmark's Midtown Promenade theater, across the street from Piedmont Park).

Let's face it: Atlanta is now booming as a go-to spot for big productions. It's the horror capital of the nation, with TV phenoms The Walking Dead, The Vampire Diaries and Teen Wolf all being simultaneously filmed in the immediate area (the town has a BIG-TIME horror fanbase, thanks to Shane Morton's continuing Silver Scream Spookshow, hosted at the historic Plaza Theater by Professor Morte (pictured above) and featuring a slew of ever-adventurous classic horror titles; Splatter Cinema, which focuses in on 80s-and-beyond scare shows; the Drive Invasion, put on every July 4th by what I would imagine is the only six-screen drive-in in the nation, The Starlight; Georgia State University's Cinefest, which has a smart program of horror and explotation cinema mixed in with indie, foreign and mainstream titles; and DragonCon, one of Big Three of the horror/sci-fi/fantasy convention success stories, bested only by San Diego's ComiCon and the New York ComiCon). But then, let's not forget that the city has attracted a number of current and upcoming non-horror Hollywood productions, like The Farrelly Brothers' reboot of The Three Stooges, the Mary Elizabeth Winstead/Amy Pohler/Lane Lynch starrer A.C.O.D., the Ben Stiller/Jonah Hill comedy Neighborhood Watch and, most amazingly, Clint Eastwood's latest, a baseball-scouting vehicle called Trouble With The Curve (co-starring Amy Adams, Justin Timberlake and John Goodman). And, last but certainly not least, Atlanta is the home of America's most successful indie filmmaker Tyler Perry, whose productions continue to redefine and broaden the scope of black cinema.

All of this must make the current festival's director Christopher Escobar (pictured above) swell with pride and not a little bit of pressure, though he showed not one bead of sweat as he hosted tonight's fabulous opening ceremonies. The 36th Atlanta Film Festival--programmed by Charles Judson, Tom Davia and Christina Humphrey--feels truly international yet simultaneously has a distinctly Atlanta feel, as there are about 50 films represented at the fest that have hometown ties. That just absolutely reflects the frenzy of filmic activity going on in the ATL.

So, enough. What about the movies? Well, that's what I'll be focusing on for most of my subsequent posts this week. As for tonight? Here are my reports: I started off my movie-watching tonight with a tour of the world, documentary-style. I elected to first see a series of sketch-sized shorts:

Among Giants (by Chris Cresci, Ben Mullinkosson and Sam-Price Waldman) is a vibrantly photographed look at a young man named Farmer as he actively protests the logging of California redwoods by taking defiant refuge in these century-old sentinels' towering branches. A beautifully quiet and purposeful piece, Among Giants portrays a necessarily simple yet ridiculously complicated life in the treetops (yeah, he cooks and sleeps and weathers the elements up there, communicating only with his fellow protesters by hollers and daring twixt-tree rope line). It seems an impossible way to be, but this 10-minute film successfully portrays a labor of love by one man fascinated to the extreme by the outdoors, and by the majesty of these unfairly victimized American jewels. If I had one complaint with this beautifully-paced student film, it's that it's way too short. This is a feature in the making, and perhaps a terrific one.

The same complaint about brevity could be leveled to the nth degree at Tom Pietracik's Saloon, which spends a colorful though quick four minutes with the workers and patrons of a barber shop in New Dehli, India. The faces and fascinating grooming methods of the barbers here are rich in detail, but the film is disappointingly over before it begins. Scored with typically lively music from Slumdog Millionaire Oscar-winner A.R. Rahman, I ultimately had to really wonder why the film was made if it was only going to give us a teensy taste of its gorgeous atmosphere.

Sasha Nakhai and Rich Williamson's The Sugar Bowl does more justice to its subject. Set in the island of Negros in the Philippines, it tells of a formerly wealthy region that profited mightily from worldwide consumption of its sugar cane crops before the Ferdinand Marcos regime. But Marcos' corruption sent the region spiraling into poverty when the 80s rolled around. Then, as an extra kick, the U.S. found a more fattening, worse-tasting replacement for sugar in high fructose corn syrup. Says the film's most impassioned (and frank) interviewee "Everything has changed now, McDonald's-style." And so his family once-thriving plantation has become a museum and a haven for Filipino art and culture. Again, though, The Sugar Bowl seems like only a preview for something more. But at least it's an almost complete intro to the heavings and struggles of an ambitious country's people.

My favorite film of the night was Ik Ben Echt Niet Bang! (I'm Never Afraid!), a heartfelt tale of another kid with a bike. This film, from the Netherlands' Willem Baptist, captured my affection from the beginning as it incisively follows Mack, an 8-year-old biking and motocross champ with a bedroom full of trophies and a pile more up there in the attic. This haunting piece begins with a hint of death, as Mack confesses his miraculous survival, though the film doesn't detail much on this at all. Instead, it begins with a funny exchange between he and his sister, as he discusses her extreme allergies to a whole host of foods (she seems charmingly annoyed by her little brother). I'm Never Afraid is full of life, though, when it glimpses Mack's extreme athleticism and hyper-manly worldviews; he's a superstar in the making. It's only when Baptist's camera accompanies him to the doctor that we find out about his unusual malady. But, for Mack, this is only a side issue. He's all about winning, and so this film (nicely scored with a host of Ennio Morricone movie-music cuts) ends precisely where it should, with a splatter of mud on the camera lens as Mack and his bike take off toward another finish line. This is an elegant little painting that, for a change, feels utterly complete.

The Capital Buzz is also a film that has a handle on its scope. Produced by students at George Washington University in Washington DC (including producer Diana El-Osta and writers Shweta Banerjee and Allee Sangiolo), it begins as a treatise on the importance of urban beekeeping in a trembling time where the world's bee population is dangerously dying off, threatening the world's food supply. But the filmmakers' eyes shift (perhaps not so smoothly) and find a beguiling subject in Jeff Miller, a middle-aged hobbyist beekeeper who stores his apiary atop his Georgetown apartment building, where he handles the insects often barefoot and without the seemingly requisite veils, suits, and smokers (mostly out of laziness, he amusingly admits). Through delightful interviews with Miller as well as his hilariously precocious daughters and long-suffering wife, The Capitol Buzz finds its footing in telling not a tale of activism (though it is that) but instead one of a man who's found a hard-fought happiness by doing his own small part to keep the pollen flowing. The movie's a little clunky in its photography and sound, but it has heart and sometimes heart is all you need.

Finally, in this program, we have unabated and potty-mouthed laughs with Cardboard Titanics, Sam Frazier Jr.'s simple doodle about a weekend raft race in Birmingham, Alabama in which contestants vie for homemade trophies by constructing their watercrafts out of cardboard and racing them a short distance. The filmmaker himself admitted that his movie was just a lark, and it shows...but it works in that it hands perhaps exhausted audiences something with a bit more beer-fueled fun to it. Everything about this movie's homemade, actually, but that don't mean it's not effective. Hey, Georgia's now-defunct Chattahoochee River Raft Race became a big deal in the 70s and 80s (before the event became to big for its britches and the river itself became too polluted). There's no reason all of this couldn't happen again in Birmingham--minus the drama, we hope...

After this program, it was time for the festival's Opening Night offering, Kat Coiro's amiable L.A.-based romantic momedy L!fe Happens, starring Krysten Ritter as a one-time scenester who finds herself suddenly saddled with a baby after a fling with a flippant Australian surfer (with music notes tattooed on his neck). Ill-prepared for the requisite parental demands, Ritter's Kim whines to best friend and roommate (Kate Bosworth) "This is so hard. No one ever tells you how hard this is going to be." Bosworth is incredulous, in her character's wisenheimer way: "Yes, they do, Kim. That's pretty much all people say."

L!fe Happens might trade in a bunch of cliches, and enumerating them is inevitably gonna sound like I'm beating up on the movie; still, I have to be up-front here. Hey, it's got Kim's bitchy employer, a self-absorbed dog groomer who hates kids (played with Karen Black-like fun-scariness by Kristen Johnson). There's the hunky guy Kim sets her moony brown eyes on (Geoff Stults), who comes complete with amusingly daft best friends Jason Biggs (as a quirky divorce lawyer who offers Gummy Bears to his client out of a regal oak box) and Justin Kirk (saddled with a bad haircut, a funky mustache and way too much confidence). Bosworth is a blondie self-help author who doesn't like the term "self-help." And they live in a house that's way out of these destitute girls' price range with a squeaky 21-year-old virgin (Rachel Bilson) who keeps taking slinky jobs that exploit her good looks. Underused is Ritter's Pop-Pop played by Seymour Cassel, a Cassavetes veteran who's still in there punching away for indie filmmakers, even if this time they can find little for him to do (c'mon, give this accomplished actor ONE major scene, at least)

But if anything sells this movie, it's Ritter, who gives the film her all and never veers into parody. We can always believe in and have no problem siding with her. It's a wry and fresh performance. Some might say the movie's more bubbly than funny, and I might agree. But in this age where few films pass the intriguing Bechdel Test, it's nice to see women talking about their lives and ambitions, and not only about those of the guy's they're bedding. Yeah, sometimes the fast talking and hyper split-screen action brings L!fe Happens down a notch. If there were more movies about women's concerns hitting the screen, we might have cause to complain; instead, we should enjoy what we get on this score. L!fe Happens is what a call a Saturday-afternoon movie; it's breezy, undemanding fun. I only wish Coiro and Ritter had more box-office power to forego the sitcom antics and approach the kind of layered insight that a filmmaker like Nicole Holofcener does with movies like Lovely and Amazing and Friends with Money (the latter of which is amusingly referenced here). But maybe this team will be able to achieve this in the future; as it stands, this is a friendly start.

My first night at the festival closed with a regal after-party at the stunning antiques house/special event parlor Paris on Ponce, where we were all treated to wines and sweetmeats as well as another film, a Georgia-bred gem by Raymond Carr called Old Man Cabbage. A stylish homage to silent cinema that successfully skates the fine line between narrative short and music video, its main feature could arguably be either the sweet relationship between a pair of chagrined acrobats or the raucous performance by ragtime jazz combo Blair Crimmins and The Hookers (who accompanied the film live, silent-movie style). Either way, watching Old Man Cabbage was an effervescent and flashy way to cap the opening night of the 36th Atlanta Film Festival.

Sunday, March 4, 2012

Film #149: POLTERGEIST

The summer of 1982 was virtually dominated by the spectre of Steven Spielberg, first with his mammothly successful E.T. The Extraterrestrial, and then with Poltergeist, a now-classic, sometimes sappy, sometimes genuinely frightening horror film, officially directed by Tobe Hooper (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) but with identifiably Spielbergian touches (he produced and co-wrote the film). The film ends up being sort of comparable to a Beatles song where you can pretty clearly tell which part was written by Lennon and which by McCartney. It's a oil-and-water solution, Hopper and Spielberg, and it doesn't always work, but when it does, it's super-charged (in a way, it feels like their take on William Friedkin's The Exorcist). Unfortunately, the baggage of a few really bad sequels (stay away from them) and a weird behind-the-scenes backstory have often obscured how really entertaining this 30-year-old movie is on its own.

The summer of 1982 was virtually dominated by the spectre of Steven Spielberg, first with his mammothly successful E.T. The Extraterrestrial, and then with Poltergeist, a now-classic, sometimes sappy, sometimes genuinely frightening horror film, officially directed by Tobe Hooper (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) but with identifiably Spielbergian touches (he produced and co-wrote the film). The film ends up being sort of comparable to a Beatles song where you can pretty clearly tell which part was written by Lennon and which by McCartney. It's a oil-and-water solution, Hopper and Spielberg, and it doesn't always work, but when it does, it's super-charged (in a way, it feels like their take on William Friedkin's The Exorcist). Unfortunately, the baggage of a few really bad sequels (stay away from them) and a weird behind-the-scenes backstory have often obscured how really entertaining this 30-year-old movie is on its own.

At 2:37 a.m., little Carol-Ann (Heather O'Rourke) is lured into a darkened room where, against the static-filled, blue-blinking light of the TV screen, she begins to perceive voices talking to her from "the other side." Concerned parents Craig T. Nelson and JoBeth Williams discover Carol-Ann touching the TV screen and famously warning: "They're heeeeere..." And so begins a spiral into terror that finds an average suburban California family getting slimed upon by some pretty pissed-off ghosts. No one is off-limits...even, as we soon find, the poor kids (Oliver Robins and Dominique Dunne are Carol-Ann's older siblings). At first, there's just some chairs moving about and the like. But when the cute li'l tykes end up getting swallowed up by their strangely-overlit closet and almost choked to death by a stuffed clown, well, something has to be done.

So when things escalate, the parents call in some experts: Network Oscar-winner Beatrice Straight as a doctor of parapsychology ambles by with her posse to record the events, and the diminutive Zelda Rubenstein, in a unique performance, blows in as a kindly super-medium set up to communicate with the ghosts. Rubenstein, with her honey-flavored southern accent and darkened glasses, is really the heart of the movie. She's was a fascinating character actress who still pops up occasionally, mostly on TV (however, she was part of the huge cast in Richard Kelly's bizarre Southland Tales, her final big-screen role before she passed away early in 2010). At four feet or so, Rubenstein was technically a "little person," having played a Munchkin in 1981's god-awful Under The Rainbow (with Chevy Chase and Carrie Fisher, about the wild goings-on with all the little people hired to be in The Wizard of Oz). At any rate, Poltergeist is largely stolen by her.

The special effects here, by Richard Edlund, Bruce Nicholson, and Michael Wood, are quite a draw, too. I'll never forget the red gaping mouth that the kids' closet morphs

The special effects here, by Richard Edlund, Bruce Nicholson, and Michael Wood, are quite a draw, too. I'll never forget the red gaping mouth that the kids' closet morphs  into, nor that hallucinatory, lengthening hallway that JoBeth Williams darts down, nor the white billowy demons of the undead and the epic implosion that climaxes the movie. And the makeup, by Dorothy Pearl, really highlights perhaps the films most terrifying scenes as the dead begin to pop up out of the ground (the gloppy sequences in the neighbor's muddy swimming pool will have you grimacing--by the way, those are REAL skeletons there, which definitely seems like a Tobe Hooper touch). Perhaps my favorite moment in the film is a maybe a quieter scene that explodes into fright: a photographer on Straight's team decides to retire to the bathroom and sees something NO ONE should see in the mirror.

into, nor that hallucinatory, lengthening hallway that JoBeth Williams darts down, nor the white billowy demons of the undead and the epic implosion that climaxes the movie. And the makeup, by Dorothy Pearl, really highlights perhaps the films most terrifying scenes as the dead begin to pop up out of the ground (the gloppy sequences in the neighbor's muddy swimming pool will have you grimacing--by the way, those are REAL skeletons there, which definitely seems like a Tobe Hooper touch). Perhaps my favorite moment in the film is a maybe a quieter scene that explodes into fright: a photographer on Straight's team decides to retire to the bathroom and sees something NO ONE should see in the mirror.  Let's not forget Jerry Goldsmith's score, which sometimes thickly ladles on the sweetness with a memorable theme, but is always more effective in the film's scarier portions. And, finally, it should be mentioned, I guess, that there's supposedly a curse on the Poltergeist family of actors, with a few of the principles in this and the sequels dying premature deaths. But most of the cast is alive--geez, Rubenstein, Nelson, Williams, Robins, Spielberg and Hooper are with us, and even Nelson's screeching, unscrupulous boss James Karen keeps on appearing in things like Mulholland Dr. and The Pursuit of Happyness . So why believe in some silly old curse? Unless, of course, it makes Poltergeist more fun for you somehow. That I understand.

Let's not forget Jerry Goldsmith's score, which sometimes thickly ladles on the sweetness with a memorable theme, but is always more effective in the film's scarier portions. And, finally, it should be mentioned, I guess, that there's supposedly a curse on the Poltergeist family of actors, with a few of the principles in this and the sequels dying premature deaths. But most of the cast is alive--geez, Rubenstein, Nelson, Williams, Robins, Spielberg and Hooper are with us, and even Nelson's screeching, unscrupulous boss James Karen keeps on appearing in things like Mulholland Dr. and The Pursuit of Happyness . So why believe in some silly old curse? Unless, of course, it makes Poltergeist more fun for you somehow. That I understand.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)