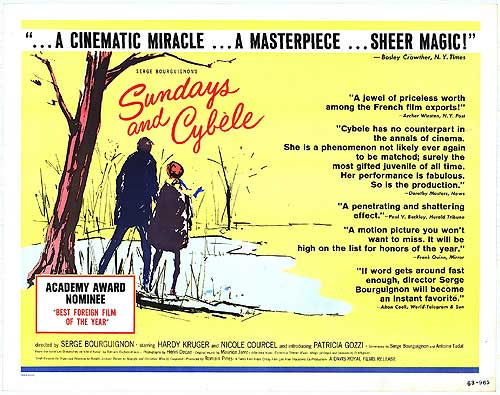

After years of merely seeing the title Sundays and Cybele bandied about, I only recently got the chance to see it courtesy of our heroes at Criterion. I had long had it on my radar, knowing that it won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 1963. And, then, in 1964, due to arcane Academy rules, it achieved that ancient and odd achievement of being nominated the following for Best Adapted Screenplay (it comes from a novel by Bernard Eschassériaux, who threw in on the screenplay, though he’s uncredited) and also for the legendary Maurice Jarre’s evocative score. When I finally got the chance to see it in 2014, I was seriously blown away by its visual acuity, intense performances and complicated emotions. I could barely comprehend its immense breadth, and immediately wanted to know more about its maker. But here I quickly found myself thwarted. Even in the age of the Internet, there are still artists about whom you can find little. And its director/co-writer Serge Bourguignon is one of them.

So here is what I have learned about him: From 1948-50, he studied at France’s L’Institut Des Hautes Etudes Cinematographiques (the IDHEC, translated as the “Institute for Advanced Cinematographic Studies,” and now known as La Fémis). This is the famed film school that spawned the likes of Alain Resnais, Claire Denis, Volker Schlondorff, Theo Angelopolis, Louie Malle, Costa Gavras, Claude Sautet, Patrice Leconte, Arnaud Desplechin, and Jean-Jacques Annaud, as well as countless other cinematic craftspeople (quite an alumni there). After traveling the world in search of material, he began helming documentary shorts in the late '50s, culminating with his Palme D’or win at Cannes for his short film La Sourire in 1960 (this short is available on the recent Criterion Collection release of Sundays and Cybele, though I must confess, I haven’t yet seen it).

After Sundays and Cybele won the Academy Award, the director moved on to making a now obscure 1965 American western called The Reward, starring Max Von Sydow and Bourguignon’s wife Yvette Mimieux (and where can we see THIS film?). His second French feature, Two Weeks in September, starring Brigitte Bardot, arrived in 1967 and has only recently been released as part of a Bardot box set. After this, Bourguignon threw in on the filming of The Picasso Summer, a 1969 drama adapted from the work of Ray Bradbury and starring Mimieux and Albert Finney (the number of filmmakers who contributed to this film were many, and effectively diluted his contribution, to the point where he’s not even mentioned on IMDb as a collaborator, and this i also a lost film). After this, he apparently divorced Yvette Mimieux (who would go on to wed Stanley Donen in 1972), and ever since, cinematically or otherwise, we haven’t heard word one from Serge Bourguignon. Outside of what’s included in the Criterion’s extras on their release of this film. I doubt one could find out anything about the man.

I can barely imagine what his life has been like being at such peaks and valleys. (Can YOU fancy being married for less than a decade to the stunning Yvette Mimieux?) But I guess he’s found happiness without making films. Even so, Orson Welles said that you only need one to be remembered, and for Bourguignon, it’s clear that Sundays and Cybele is his one. Its original title is Les dimanches de Ville d’Avray (or Sundays in Ville d’Avray, referring to the Ville-d’Avray suburb of Paris, where the film’s action takes place). Somehow, the film’s title in the Criterion days has been transmogrified into Sundays WITH Cybele, but I’m going with the title Bourguignon’s movie is most well known by–Sundays AND Cybele–which is, I find, radically more poetic. I must admit, I am fiercely curious as to the filmmaker’s abandonment of an art form of which he was a downright master. But I can easily see how someone with his baffling sensitivity would've been disillusioned with the sickening complexities of the film industry, particularly given his disappointing history with it.

When one views Sundays and Cybele, one is seeing the work of an absolute innocent–and it’s a mirror reflecting the innocence of the film’s lead characters, much like the mirror reflections we constantly see in the film’s pond waters. Any person who could make a movie like this would instantly be destroyed by any sniveling studio overlords, be they American or European. It’s a miracle that it made it as far as it did in mass acceptance. Still, in fact, this is a movie that has been, in my view, actively suppressed for many years, and it’s only now, with its Criterion release (bless them), that it’s becoming a work that has a new salvo of fans behind it. Yes, I know it was released on VHS in the early 90s; but why has it not seen screens since Criterion’s 2014 release? (I know why…) Anyway, I’m just happy to be part of the crowd that has, at least recently, embraced this masterpiece.

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out what the problem is here. We now live in a world where the kind of relationship displayed in Sundays and Cybele cannot even be conceived of without the collective population making instant judgments (and these judgments definitely make a fatal and defiant appearance in Sundays and Cybele). There is, apparently, no room in this present world for a heightened, and chaste, friendship between an adult and a child. Even mentioning this concept makes me, myself, culpable. These days, the only adults that need to be saying word one to a kid are the kid’s parents. Anyone else is suspect. And I have to say, I find this sad. How anyone can be a teacher or an adult be a friend to kids nowadays? I had many adults as friends as a kid, and I was also totally aware of how an adult could take advantage of me. Yet I forged many friendships–even ones that I still have–with non-family adults when I was young. I feel there is a madness existent now, particularly in American culture, regarding relationships between non-parental adults and kids under 18 (and even older). I understand: there are maniacs out there–maniacs who are close to, or even fellow family members with kids. But it’s just so sad. That major majority of adults–those who aren’t pedo perverts–are labeled with the same stickers as the tiny minority who are. We’ve gotten to the point that the only humans who can talk to kids are the ones who are related to them (even though it is those related to them who are the most likely suspects of wrongdoing). I think all of this–even the very notion of it–is sick. In the end, this culture has made me–a childless singleton–wary of being around kids. And how strange, and wrong, is that? Whew.

Is it possible for the world today to take a look at Sundays and Cybele and understand that it displays an intense friendship between a damaged, childlike man and a child? I wonder about that. When I first saw the movie in 2014, I immediately thought: “This is why I haven’t seen this movie. It’s been suppressed.” I think the world of children, and of adults, changed with the release of Kramer Vs. Kramer in 1979 (remember, that was the #1 box office success of that year, and in collusion with the Reagan era, was the film that let formally clueless, coked-up parents know that their kids should be their prime priority). The other big things that happened soon after, at least in American culture, were the TV films Adam (1983, about the kidnapping and death of John and Reve Walsh’s child–John Walsh later became the host of FOX’s massively successful reality crime show America’s Most Wanted) and Something About Amelia (an Emmy winner in 1984, starring Ted Danson and Glenn Close, in which the father has an incestuous relationship with his daughter). Both of these TV movies (along with 1981’s Fallen Angel, with 13-year-old Dana Hill being seduced into child porn by a jerk perfectly played by character actor Richard Masur) received massive ratings and critical acclaim, and seemed to instantly ratchet up the idea that kids–all kids, everywhere–were in stranger danger danger danger.

Why am I talking about all of this? Because when I first watched Sundays and Cybele in 2014, I immediately felt this movie was supremely weird, and wonderful, and that it might unduly offend or at least trouble the average viewer. By its end, I understood its heart. This is a movie about a heightened friendship. It is not a film about a romance, although the actual child in this relationship–played brilliantly by Patricia Gozzi–is 12 years old and openly expresses a desire to eventually marry the adult Pierre (Kruger) when she reaches the legal age of 18 (she even does the mathwork for them, and he clearly has no problem with this, though we wonder if he has any grasp of reality after his wartime experience). Kruger’s Pierre–a onetime jet pilot–has been scarred by what we see in the film’s pre-credits sequence, where he crashes his plane, downed in the early Vietnam War, right into the face of an innocent Vietnamese girl. This is how the film starkly, fastly begins, with that ridiculously contrasting black and white. With this, we can at least understand that a psychological barrier has been set up for Pierre–it’s one laden with supreme guilt.

And so, when we see Pierre first blankly connecting with Cybele, we get it. At that point, she is being abandoned by her actual father at a train stop, where she is supposed to arrive at a parochial school. As her father asks Pierre, waiting lonely at the station, to direct them to St. Maugerite’s boarding school, Cybele instantly connects with Pierre (with both of them glaring strikingly into Bourguignon’s camera). At that train stop, they smile at each other and recognize the caring in each other’s eyes. But they are separated still. Cybele demands that her father explain why she is being abandoned, but he says that he will come back and visit her. He never does. “She mustn’t cry,” Pierre says, insisting on meeting her. And he offers her pieces of a star. Pierre is a man, but a child, too. The trauma of war has left him in a state of arrest, and even regression. He’s in a cool relationship with Madeleine (an extremely sexy Nicole Courcel), one on which she places much more importance than he. When she approaches him in her underwear, clearly post-coital, and asks how he feels, he says he feels like nothing. He’s no longer ready for the responsibilities of adulthood, and though they’re sexually active, Madeleine has no idea there’s anything impeding their relationship. Neither does Pierre, frankly.

It’s difficult to see Pierre’s following of Cybele as anything but stalking nowadays, and again, that’s sad. Cybele is someone who needs love, and her father and the nuns clearly have no affection left. When her father leaves her luggage outside of the school, it’s Pierre who retrieves it, and that’s what leads to their alliance (at the subway station, we see someone exiting the train with a cello, and the auteur theorist in us think of Hitchcock’s cameo in Strangers on a Train). And then, amongst cinematographer Henri Decaë’s finest widescreen shots, we see the image shrink to a tiny silent-film circle, where Pierre realizes Cybele’s father isn’t coming back. The film is never about Pierre’s guilt for loving Cybele. Their friendship–which is never a physical relationship–is unencumbered by naughtiness. Pierre cannot remember sex, or love, and it’s only the trees in nature that spark him. He admits to his girlfriend Madeleine that he’s unhappy, and without identity. But she never believes it…that is, until she can do nothing but believe it. (At the hospital she works at, Madeleine strike up a flirtation with a doctor that later leads to darker depths.) I love that Pierre’s connection with Madeleine seems complete and faithful. He really cares for this woman, and his love for Cybele is something completely different. It’s a connection without sex, but also equally intense. Vertigo also plays a part in the film, referring to Hitchcock once again.

The images I recall most from Sundays and Cybele are the ones that involve Pierre and Cybele (who keeps her real name obscured from Pierre until just the correct moment–she tells him her name is Francoise for most of the film) as they aimlessly wander the watery park paths, their reflections dappling in the ponds they pass, with their dreamy mirror images blending their bodies in with their woodsy surroundings. I love absolutely everything about Bourguignon’s direction (key shots are framed through glass, too), and his mastery of not only black-and-white, but of widescreen photography is never less than magical (the older I get, the more I realize that the matching of Cinemascope and B&W is the stuff of complete wonder). His vivid reflections upon water are visions I have never seen assayed in quite the same way in all of cinema history. Geez, I think that I could watch this movie at least ten more times and get something new out of it. So I hope you forgive me when I say I’ve seen it only once.

Without spoiling the film for you, I should say that it is Patricia Gozzi who stands as its ultimate heroine. She’s so amazingly INTO this role. Her performance here is unmatched–she’s appealing and smart; she’s innocent, and preternaturally mature, and so she knows the limits of this relationship, even if Pierre doesn’t. In fact, she’s way ahead of him, even if she can’t truly express or understand what’s going on in Pierre’s past or present (I do love Hardy Kruger in this movie, too–it may be his most soulful role in a very long career). Make no mistake: the shattering final moments of this film will forever haunt your thoughts. There are stinging tears here. I mean, these young tears burn.

NOTE: this review originally appeared in 2015 as part of WONDERS IN THE DARK's genre overview called THE CINEMA OF CHILDHOOD. Check the whole lineup out here:

No comments:

Post a Comment