For years, I had not seen Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch in full. I had caught bits of it on TV, or maybe at the drive-in, where my mom and dad had carried me along to check it out. I’m sure my dad liked it--most dads adore The Wild Bunch--but my mom, who'd had quite enough of seeing dead bodies returning from Vietnam on TV, felt sickened by violence in movies at the time (both Bonnie and Clyde, with its bullet-riddled climax, and M.A.S.H., with its comedic treatment of medical gore, had similarly made her ill; since, of course, she's been inured to on-screen messiness). For my own part, I found the movie dull, even as a pretty with-it kid; somehow, Peckinpah had not gotten his hooks in me (I now see that The Wild Bunch is a movie that works least best on the young, and also I always knew that, on TV, it was being shown pan-and-scan, and that's just a outright no-no with what any movie geek can see is a beautifully widescreen presentation).

It wasn’t until its 1995 restoration and re-release, when I was approaching my 30s, that I finally did my duty and caught The Wild Bunch on the big screen at a four-wall theater, as it was meant to be seen. Afterwards, I could’ve kicked myself twice, three times even for not previously grasping what a powerhouse masterpiece it was, for Peckinpah’s film finally bowled me over as it did almost everyone who saw it in the late 60s/early 70s (it's certainly a movie that should be seen at least once at a theater; if you haven't experienced it as such, you're partially abandoning its strength). From its very first scene--that staccato credits sequence portraying the titular bunch trotting past a group of joyful kids cackling as thousands of fire ants overtake two deadly but hapless scorpions (a mirror of the film's famous conclusion)--The Wild Bunch aims to encapsulate the brutality of criminally-minded men and, simultaneously, their deeply-held longing to regain some modicum of innocence, honor and compassion. In its dichotomies, Peckinpah's picture is like no other. It set a template for a few decades worth of film output behind it.

In it, William Holden (who, while struggling to vanquish an alcohol-induced career slump, thankfully won the lead over a then-too-vibrant Lee Marvin) plays the aged, tired Pike Bishop, a former Army man now commanding a group of droopy ne'er-do-wells through a rather inert series of bank and train hold-ups. Alongside him: the unfailingly loyal Dutch Engstrom (Ernest Borgnine, in a sweet mid-career boost); the filthy Brothers Gorch, Lyle (Warren Oates) and Tector (Ben Johnson, in perhaps the first of his major roles after John Ford's Wagon Master); Angel, the handsome Mexican bandit (Jaime Sanchez, notably the most youthful and idealistic of them all); and character actor Edmond O’Brien as Freddie Sykes, the grizzled, tobacco-dribbling horseman (giving Sierra Madre's Walter Huston a run for his money as the definitive unkempt mountain man). Most of the rest of the bunch--including Bo Hopkins as the too-briefly-seen Crazy Lee ("Well, how'd you like to kiss my sister's black cat's ass?")--are dispatched in the film’s first big showpiece: the robbing of the bank in that sleepy Texas town too busy railing against the evils of drink to notice they’re all about to get blown to bits (gotta love a movie where the first actor you see with a speaking line is the inimitable Dub Taylor).

It’s the bunch that starts the gunfire, but it’s Deke Thornton’s gang of money-hungry buzzards that escalates it, looking to get every penny they can, even if it means shooting total innocents and then robbing their pockets, or the shoes off their feet. Thornton is played with a gorgeous world-weary sadness by Robert Ryan; it’s clear that his character is not enjoying this assignment. Even though he and Pike ended their relationship on bad terms (in an essential flashback edited back into the movie only in its re-release), he still sees more honor in his nasty work with Pike than he does with the liquored-up trash he’s riding with now (L.Q. Jones and Strother Martin are extremely memorable here as the scummiest of Thornton's crew, complete with gentle homosexual undertones and loud bickering over the corpses they, together, pick clean). But soulless railroad man Harrigan (a mustache-twirling Albert Dekker, as maybe the most horrible person in the movie) slams the hammer down on Thornton, and sets him on his journey: “30 days to get Pike or 30 days back to Yuma. You’re my Judas goat.”

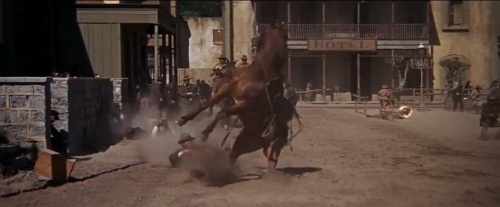

The opening scene has long been called a ballet of blood and for justified reasons. Louis Lombardo’s superb editing here ratchets up the tension, with the sound of rapid heartbeats as background, until the sequence literally explodes--if any movie "explodes," this one does--in a cataclysm of shotgun lead, trampled townspeople, bloodied henchmen, falling bodies, crumbling storefronts, rearing horses, crushed dreams, and frightened children (there are almost endless shots of babies and kids all throughout the film, as a callback to the return-to- and destruction-of-innocence theme; women, however, do not fare nearly as well here). There is just simply nothing in cinema history like this sequence, and any filmmaker who tiptoes even slightly near it is immediately accused of ripping off Peckinpah’s mastery (only Walter Hill has gotten away with aping the Peckinpah style in his wonderful The Long Riders, a movie that should be part of this WONDERS IN THE DARK retrospective and which respectfully sidled up next to The Wild Bunch but, because of its 1980 release, didn't get much resultant controversy).

This stultifying sequence is no less than the introduction of a more modern depiction of violence in movies: a violence correctly fraught with horrible consequences. It’s this chief aspect of this film that shook cinema in 1969; even after Bonnie and Clyde, absolutely no one was ready for such an onslaught (though I don't really wanna give the impression that the depiction of violence is ALL this film's about). But Peckinpah was tired of the bang-bang-you’re-dead cleanliness of westerns and, seeing that the genre was near the end of its run, he clearly needed to put the final exclamation point on his view that bloodletting had to be seen in all its scuzzy goriness in order to be understood and, finally, perhaps vanquished (only problem is, on-screen violence continued to get more graphic afterwards; surely the cynical Peckinpah could've seen THAT coming, and we have to wonder if he blamed himself, in his final years, for heightening movie cruelty; that said, if Peckinpah didn't do it, then someone else surely would have).

After discovering the robbery's bounty is not all they thought it would be, in a scene that underlines both the fissures in the bunch’s alliance and the good humor that cements their bond, it’s up to Pike to find them something honorable--and profitable--to chase (he admits to Dutch that he‘d like to "make one good score and back off"). Taking refuge in Mexico, it’s the big-eyed Angel who leads them to this mission, after suggesting they take a siesta in his idyllic home village (photographed in haunting smoky blues and greens by Lucien Ballard, who does the best work of his long career all throughout the film). In the village, the bunch reconnect with joy, dancing with senoritas while drunk with happiness and passion (one of the village elders responds to their abandon when he says, in one of the film‘s key observations: "We all dream of being a child again, even the worst of us. Perhaps the worst most of all.")

In the film’s most moving scene, this bunch--this

wild bunch--are given an inspiring send-off by the Mexican villagers,

who soulfully incant the mournful “La Golondrina” as tribute to their

heroes' new mission: to find the General Mapache (in a superbly greasy

performance by Mexican film director Emilio Fernandez), who recently

raided the village, killed their leaders, and stolen their women,

including Angel’s paramour. I adore this scene of ardor and heroics; it

really makes me weep every time I watch it. It’s the final, gigantic

tribute to a group of men who’ve probably done nothing worth paying even

slight tribute to in their whole lives. It’s their awakening, and it’s

the memory they each take to their graves (that’s why the scene is

called back in the film’s final frames). Absolutely no one--not even the

most hardened psychopaths--could walk the tributary gauntlet they walk,

tipping their hats in respect to the noble poor and accepting generous

flowers from the ladies, without being completely transformed by the

experience.

In the film’s most moving scene, this bunch--this

wild bunch--are given an inspiring send-off by the Mexican villagers,

who soulfully incant the mournful “La Golondrina” as tribute to their

heroes' new mission: to find the General Mapache (in a superbly greasy

performance by Mexican film director Emilio Fernandez), who recently

raided the village, killed their leaders, and stolen their women,

including Angel’s paramour. I adore this scene of ardor and heroics; it

really makes me weep every time I watch it. It’s the final, gigantic

tribute to a group of men who’ve probably done nothing worth paying even

slight tribute to in their whole lives. It’s their awakening, and it’s

the memory they each take to their graves (that’s why the scene is

called back in the film’s final frames). Absolutely no one--not even the

most hardened psychopaths--could walk the tributary gauntlet they walk,

tipping their hats in respect to the noble poor and accepting generous

flowers from the ladies, without being completely transformed by the

experience.The detailed screenplay, by Peckinpah, Roy Sickner and Walon Green, is unusual in numerous ways, one of which is its second-act shift from western genre territory into almost war (or crime) movie-land, with Mapache (under the thumb of a couple of Nazi-precursor German consultants) conducting his federales against the revolutionaries, and the bunch--all US Army veterans--once again abandoning their morals and agreeing to heist a trainload of American guns for the General's nefarious use. Pike’s men are to split a cache of gold coins as payment, but Angel--bitter over the subjugation of his village and the theft of his woman (whom he’d rather see dead than with Mapache)--asks for a crate of guns and ammo instead of gold, so that his village can fight against the general. Angel's compatriots see this as a risky though honorable trade-off, and so they comply. This leads us to the brilliantly tense train heist scene--a centerpiece of the film which Peckinpah slyly directs with almost no dialogue or music cues. Only the rhythmic sounds of the train appear on the soundtrack, heightening the strain of this enormously entertaining sequence which culminates in one of the hugest stunts ever seen in cinema: the determined destruction of the dynamited bridge, with Deke Thornton’s men on it (the resultant blast is so massive--by Peckinpah's design--that its shockwave visibly stuns Holden on-screen).

It's nuts, the innumerable moments I love in The Wild Bunch--moments those rabid fans of this cultiest of cult movie will be very familiar with: William Holden’s insanely suitable first major line (“If they move, kill ‘em," which not only became the title of David Weddle’s authoritative biography of the self-destructive Peckinpah, but also signifies the second upon which Peckinpah’s freeze-framed director’s credit appears, as the capper to that energetic credits sequence, and perhaps the autograph on a career devoted to a strange breed of sadly heartless humanity; it also might be the one single line of dialogue that defines the western genre as a whole); the way the temperance league members can’t--or maybe won’t--quite follow Dub Taylor’s pledge of alcohol abstinence; Pike and Dutch’s compact and repeated comedy routine (Pike: “Get up, ya lazy bastard”); Lyle Gorch being schooled in what the term “in tandem” means; Pike's regretful realization that Crazy Lee is actually Freddie Sykes’ now-dead grandson; Dutch scorching his fingers on and then spitting out Freddie’s awful coffee; Pike falling off his horse, to the bunch's amusement, and then agonizingly getting back up on the saddle again, to their respect; Lyle, at the Mapache headquarters, complaining about being set off at a side table from the decision makers, and then disdainfully leering at the sodden general (“Well, look at him--ain’t he the one?”); Angel's final exchange with the woman who betrayed him, all in unsubtitled Spanish, and all before he assassinates her, with an unforgettable, very-close zoom-in on her rapaciously laughing face, and then followed by a dismissive response from the general, who sees her very funeral as merely an irritant; Lyle and Tector cavorting in both wine and water with two portly Mexican women; the unfailingly ridiculous Mapache riddling the town with bullets while firing a bulky machine gun; the wacky scene with the gang sharing a single celebratory bottle of hooch; a toothy Alfonso Arau (another notable Mexican film director) as one of Mapache’s deputies, sent to negotiate with the bunch, pleading mightily with Pike to “Please…cut the fuse.” Like any devoted cultist, I eagerly wait for all these scenes whenever I watch the movie.

And maybe my--and everybody's--single favorite exchange in the film: where Pike finally glances around the Mexican brothel where he's had his last woman (in a life probably filled with only whores), where he's feeling bad for the good-hearted, romantic man they left behind, feeling sorry for the damnable bastard he's become and, with Ballard’s luminous lighting catching JUST the correct angle on Holden's stunning blue eyes, then saying to the rest of his fellow bastards simply “Let’s go.” And Lyle’s also brilliantly terse answer: “Why not?” No more words are needed (Borgnine's Dutch stands outside of the brothel, just waiting for the right answer). Thanks to Peckinpah's writing and direction, both Holden and Oates would never match their career-defining moments here (though Oates had quite a colorful filmography ahead of him).

Thus begins their final march--a march towards immortality, a victory march, a death march and a march for freedom. These iconic actors--this iconic moment--this stroll--a moment improvised on location, sculpted in time--towards a final showdown with Mapache's bacchanal at Agua Verde, and set to Jerry Fielding’s terrific brass-and-percussion-driven score--well...there's just nothing like it And after an unbelievable, unbelievable denouement--this incredibly grisly climax, deeply emotional and desperate, with its quicksilver editing, loud and copious gunfire, exquisite choreography, hundreds of bodies (mostly dead or dying), fleet moves and slow-motion movements, and then ending with Dutch's final heartbreaking reach out to Pike--after this, nothing...nothing... in movies would ever be the same (and yet nothing in movies would really ever match it). The Wild Bunch, surprisingly humanistic and supremely lovely and stunning in its understanding of depravity and its limitations, is not simply the westerns to end all westerns; it's one of the ultimate examples of pure cinema. That's how landmark great it has always been, and how mesmerizing it still is.

Pike Bishop: We're not gonna get rid of anybody! We're gonna stick together, just like it used to be! When you side with a man, you stay with him! And if you can't do that, you're like some animal. You're finished! We're finished! All of us!

NOTE: This post originally appeared as the #7 entry in Wonders in the Dark's countdown of the 60 greatest westerns.

No comments:

Post a Comment